Mediation Equity Model: Legal Framework for Strengthening Mediation Institutions as an Alternative Dispute Resolution in Indonesia’s Tourism Sector

##plugins.themes.bootstrap3.article.main##

Abstract

The relationship between employers and workers in the context of industrial relations in Indonesia’s tourism sector is often vulnerable to disputes. This sector, as one of the pillars of the national economy, faces complex interests between workers who seek to protect their rights and employers who focus on maximizing profits. With the increasing development of the tourism sector post-pandemic, issues such as layoffs and dissatisfaction with working conditions are becoming more prominent. These disputes have become urgent issues, especially considering the tourism sector’s characteristics that are susceptible to economic fluctuations. The dispute resolution process through bipartite negotiations, as regulated in Law Number 2 of 2004, often encounters deadlocks, necessitating the need for tripartite mechanisms such as mediation as a non-litigation dispute resolution option. The characteristics of industrial relations mediation, although designed to seek solutions impartially, face various obstacles in their implementation, including a lack of skilled human resources and financial support. Through an in-depth study of the applicable regulations, existing mediation practices, and the challenges faced, this research proposes concrete steps to improve the effectiveness of mediation in resolving industrial relations disputes in the tourism sector. The results of this study are expected to contribute to the creation of a harmonious and sustainable industrial climate in Indonesia’s tourism sector.

Keywords: Mediation equity model, dispute resolution, workers, employers, tourism sector.

Introduction

The relationship between employers and workers within the framework of industrial relations is one of the relationships prone to disputes.[1] The tourism sector in Indonesia, as one of the economic pillars, is an economic sector with characteristics that make it susceptible to industrial relations disputes between workers and employers. This is due to the complexity of the relationship, which involves differing interests between the two parties. Workers often seek protection of their rights, while employers strive to maximize profits in a competitive and dynamic business context. With the increasing demand for tourism post-pandemic, these disputes are becoming more apparent, especially concerning issues such as termination of employment (TOE) and dissatisfaction with working conditions.[2]

Industrial relations disputes in the tourism sector are becoming an increasingly pressing issue to address, given the sector’s vulnerability to economic fluctuations and job uncertainty. The tourism sector, which encompasses various industries such as hotels, restaurants, and transportation, often faces challenges in maintaining harmonious relations between workers and employers. Worker dissatisfaction with working conditions, wages, and minimal legal protection can trigger disputes that potentially disrupt company operations and harm all parties involved. Along with the development of the business world closely linked to the tourism sector, it is crucial to have an effective and efficient dispute resolution mechanism. With a good dispute resolution mechanism in place, industry players can focus more on improving the quality of their services.[3]

In the context of industrial relations dispute resolution, in every industrial relations dispute, the prevailing laws and regulations mandate that the worker/laborer or the labor union/worker union and the employer must first attempt to resolve the issue through bipartite negotiation, as stipulated in Articles 6 and 7 of Law Number 2 of 2004 concerning the Settlement of Industrial Relations Disputes (UU PPHI)[4]. This process aims to reach a mutually beneficial agreement, where both parties can convey their interests and expectations before moving to the next stages of dispute resolution. However, resolving industrial relations disputes through this bipartite mechanism often reaches a deadlock, where both parties fail to achieve the desired agreement. When bipartite negotiations between the worker and the employer do not reach an agreement, proven by a final report stating that the bipartite negotiation has failed, the parties can then resolve their dispute through tripartite mechanisms such as mediation, conciliation, or arbitration, as regulated in Articles 8 to 54 of the UU PPHI, which can be an option in dispute resolution aimed at providing a fair solution for all parties involved.[5]

Mediation, as one of the dispute resolution methods, is a negotiation that has a unique characteristic because it involves a neutral mediator from a government agency.[6] The resolution of disputes through mediation is carried out by a mediator located in every office of the agency responsible for manpower affairs at the Regency/City level. This mediation process is designed to broker the conflict and seek a joint solution without siding with either party. Although mediation is expected to reduce tension, there are still weaknesses in the institutional arrangement and the implementation of mediation itself. Many obstacles arise in the implementation of mediation, including a lack of skilled human resources and adequate financial support to optimally run the process. Previous research by the author titled “Mediation Equity Model: Legal Framework for Strengthening Mediation Institutions as an Alternative Dispute Resolution in Indonesia’s Tourism Sector”, which took the tourism area of Mandalika, West Nusa Tenggara as its research location, showed that various weaknesses and constraints still exist in the implementation of Industrial Relations Mediation as a choice for resolving disputes between workers and employers in the tourism sector.

There is similar previous research that has been conducted on the topic of industrial relations mediation, which includes: “Paradigmatic Problems of Industrial Relation Dispute Settlement on the Perspective of Pancasila Industrial Relations”, by Aries Harianto[7] - Journal of Law and Legal Reform, Year 2024; “Konsep Penyelesaian Perselisihan Hubungan Industrial Antara Serikat Pekerja Dengan Perusahaan Melalui Combined Process (Med-Arbitrase)” (The Concept of Industrial Relations Dispute Settlement Between Labor Unions and Companies Through a Combined Process (Med-Arbitration), by Rai Mantili - Jurnal Bina Mulia Hukum, Year 2021;[8] “Peran Dinas Tenaga Kerja dalam Proes Mediasi Penyelesaian Permasalahan Hubungan Industrial” (The Role of the Manpower Office in the Mediation Process for Resolving Industrial Relations Issues), by FA Dermawan, B Sarnawa - Media of Law and Sharia, Year 2021[9]; “Reformasi Hukum Dan Hak Asasi Manusia Dalam Penyelesaian Perselisihan Hubungan Industrial” (Legal and Human Rights Reform in the Settlement of Industrial Relations Disputes), by H Arsalan, DS Putri - Jurnal HAM, Year 2020;[10]

The above-mentioned studies generally aim to dissect the resolution of industrial relations disputes, mediation specifically, and the development of mediation as a mechanism for resolving industrial relations disputes. This research offers novelty compared to previous studies because it focuses on the tourism sector, adapting to the dominant characteristics of disputes that occur in this sector. Furthermore, this study also attempts to map the normative weaknesses of mediation regulation, referring to the existing Industrial Relations Dispute Settlement Law (UU PPHI) and related regulations, as well as mapping the empirical constraints of mediation implementation, by conducting field research in Indonesia’s tourism hubs, based on the existing conditions on the ground. This subsequently serves as the basis for formulating a strengthened mediation as an effective and efficient non-litigation option for resolving disputes in the tourism sector in the future.

Although industrial relations mediation in Indonesia has been widely discussed academically, existing studies have mostly focused on the manufacturing, plantation, or general labor sectors. This study specifically examines the effectiveness and institutional challenges of mediation in the tourism industry. This sector is characterized by seasonal workers, informal work arrangements, and vulnerability to economic shocks, which still have limitations. In addition, empirical studies that integrate the normative framework of the Industrial Relations Dispute Resolution Law with the reality on the ground in tourism centers such as Bali, Mandalika, and Lombok are still rare. This indicates a significant research gap, a need to understand the extent to which the current mediation framework functions in resolving disputes in the tourism sector, and to identify the legal and institutional reforms needed to improve its effectiveness.

Therefore, given the lack of effectiveness in the implementation of a norm concerning the effectiveness of industrial relations dispute settlement in the tourism sector, it is necessary to formulate an institutional strengthening of mediation to enhance the effectiveness of industrial relations dispute settlement in the tourism sector. This research includes 3 problem formulations, which are:

- What are the characteristics of the Industrial Relations Disputes currently occurring in the Tourism Sector?

- Is the current Institutional Arrangement for Industrial Relations Mediation, which refers to the Industrial Relations Dispute Settlement Law (UU PPHI), representative enough to be used as an option for resolving industrial relations disputes in the Tourism Sector?

- What is the formulation for Institutional Strengthening of Mediation as an effective Non-Litigation Option for Resolving Industrial Relations Disputes in the Tourism Sector?

Methodology

This research adopts a normative legal study approach, supplemented by field research (empirical) to produce a comprehensive analysis. The normative design focuses on literature review, utilizing the conceptual approach and the statutory approach to identify the normative weaknesses of industrial relations mediation regulations, particularly in Law Number 2 of 2004 concerning the Settlement of Industrial Relations Disputes (UU PPHI) and related implementing regulations. The primary data for this section consists of statutory regulations, supported by secondary data such as legal literature, journals, and court decisions. Meanwhile, the empirical design uses a factual approach through field research aimed at mapping the obstacles and implementation practices of mediation on the ground. Primary empirical data is collected through in-depth interviews.

The location for the field research is focused on Indonesia’s tourism hubs, taking case studies in the Manpower and Transmigration Office of West Nusa Tenggara Province and the Manpower Office of Bali Province, chosen due to the high volume of industrial relations dispute cases in the tourism sector. Primary data collection is conducted through structured interviews with a total of 6 (six) respondents divided into three categories: 2 Industrial Relations Mediators (1 from each Office), 2 Representatives of Trade/Labor Unions (actively handling Termination of Employment and Rights Disputes in the hotel/tourism sector), and 2 Representatives of Employers (HRD/Legal) from tourism companies (5-star hotels) that have undergone the mediation process. This data collection is scheduled to be phased between June and September 2024. The collected data from both approaches will then be analyzed qualitatively, presented in a descriptive-analytical form, with the final goal of formulating a Mediation Institution Reinforcement Model (Mediation Equity Model) as an effective and efficient non-litigation dispute resolution option in the tourism sector.

1.Characteristics of Industrial Relations Disputes in the Tourism Sector

Initially, the relationship between employees and employers was purely civil in nature. However, due to the existence of a superior-subordinate relationship or a power dynamic, it became highly vulnerable to exploitation, regardless of its form. Given this condition, the state needs to be present in resolving the disputes that occur in the employment relationship through the dispute resolution mechanism regulated in the Industrial Relations Dispute Settlement Law (UU PPHI).

The relationship between employees and employers is a power relationship because there is one who holds power (the employer) and one who is subjected to it (the employee). The disparity in industrial society resulting from the unequal relationship between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat leads to industrial conflict. Furthermore, industrial relations are closely tied to the interests of both employees and employers, which consequently creates the potential for disagreements and even disputes between the two parties.[11]

In an industrial relations dispute, there are three main parties involved in the scope of resolution: the employees (labor union), the employer, and the government. Industrial relations disputes can manifest in various forms, which are then categorized into several classifications of disputes within the Industrial Relations Dispute Settlement Law (UU PPHI).

In general, the provision of Article 1 point 1 of the Industrial Relations Dispute Settlement Law (UU PPHI) defines an industrial relations dispute as: Differences of opinion resulting in conflict between the employer or association of employers and the employee/worker or labor union/trade union due to a dispute of rights, dispute of interest, dispute over termination of employment, and a dispute between labor unions/trade unions within the same company.

The types of disputes referred to are regulated in Article 2 of the Industrial Relations Dispute Settlement Law (UU PPHI), which includes, but is not limited to:

- Dispute of Rights (Perselisihan Hak): “A dispute arising from the non-fulfillment of rights, resulting from differences in the implementation or interpretation of the provisions of laws and regulations, employment agreements (work contracts), company regulations, or collective labor agreements” (Article 1, point 2).

- Dispute of Interest (Perselisihan Kepentingan): “A dispute arising in the employment relationship due to a lack of consensus regarding the creation, and/or amendment of working conditions stipulated in the employment agreement, company regulations, or collective labor agreement” (Article 1, point 3).

- Dispute over Termination of Employment (Perselisihan Pemutusan Hubungan Kerja - PHK): “A dispute arising from a lack of consensus regarding the termination of the employment relationship by one of the parties” (Article 1, point 4).

- Dispute Between Labor Unions/Trade Unions Within One Company (Perselisihan antar serikat pekerja/serikat buruh dalam satu perusahaan): “A dispute between a labor union/trade union and another labor union/trade union within only one company, due to a lack of consensus concerning membership, the exercise of rights, and trade union obligations” (Article 1, point 5).

In a practical context, referring to the field research conducted, especially in the tourism sector, a phenomenon was also found where industrial relations disputes within the tourism context are dominated by disputes over Termination of Employment and Disputes of Rights. This aligns with the conceptual definition of these two types of disputes, which emphasize the non-fulfillment of rights that should be obtained by the employees as regulated in the laws and regulations and the autonomous rules applicable within the company (Employment Agreements, Company Regulations, Collective Labor Agreements) for disputes of rights. Furthermore, there is a rampant condition of termination of employment based on various disputed reasons/grounds, as well as the fulfillment of severance pay and other economic rights following the termination of employment at the company.

This phenomenon is supported by data indicating that, nationally, based on a survey conducted by the Ministry of Manpower of the Republic of Indonesia in 2020 (during the pandemic period), approximately 88% of companies were impacted, resulting in losses to company operations.[12] The tourism sector, with its characteristic high sensitivity to market changes and crises, serves as a clear example of the high number of Termination of Employment (PHK) and Rights disputes. The survey from the Indonesian Ministry of Manpower in the same year, which indicated 88% of companies were impacted by the pandemic, is directly reflected in this sector. Many hotels, restaurants, and travel agencies were compelled to implement efficiency measures, often resulting in mass layoffs. This situation was also evident in subsequent years, consistently showing a trend where PHK disputes remain the most dominant type of dispute in the tourism sector, followed by Rights disputes, which have an overlapping character.

On the other hand, the general labor condition in Indonesia, referencing data reports from the Ministry of Manpower of the Republic of Indonesia, also shows a similar situation, where there were 7,566 industrial relations dispute cases throughout 2024, dominated by Termination of Employment (PHK) disputes as the most frequently reported type, totaling 5,192 cases.[13]

The phenomenon of the high number of disputes is closely related to the need for effective, efficient, and fair industrial relations dispute resolution mechanisms for the parties involved. These disputes must go through the settlement mechanism regulated in the Industrial Relations Dispute Settlement Law (UU PPHI). Its success, therefore, becomes one of the proving grounds for the dispute resolution mechanism set out in the UU PPHI, particularly at the stage of bipartite negotiation, the tripartite mechanism, or through resolution via the Industrial Relations Court. The high number of Termination of Employment (PHK) disputes, reaching 5,192 cases in 2024, proves that the PHK process does not always run smoothly. Even though companies often claim PHK is carried out for efficiency, workers’ rights, such as severance pay, long service award pay, and compensation for rights, are frequently not fulfilled in accordance with the Labor Law and its derivative regulations. Aside from PHK, Disputes of Rights are also a major problem, with 2,033 cases in 2024. These include disputes related to unpaid overtime wages, allowances, or bonuses not provided as stipulated. In the context of tourism, where working hours are often irregular and dependent on seasons, these kinds of disputes are very common.

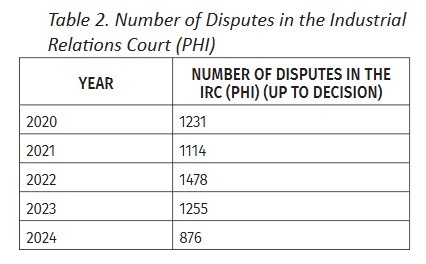

On the other hand, it was also found that the number of disputes that were submitted to and resolved by the Industrial Relations Court over the past five (5) years is still considered high. This indirectly indicates that there are still various weaknesses in the current non-litigation mechanisms for resolving industrial relations disputes in Indonesia.

The table above shows data on the number of disputes submitted to (up to the point of decision) the Industrial Relations Court in 2020, reaching 1,231 cases,[14] in 2021, it reached 1,114 cases,[15] and in 2022, it experienced a surge, reaching 1,478 cases.[16] Meanwhile, in 2023, 1,255 cases were recorded as resolved at the Industrial Relations Court.[17] Meanwhile, in 2024, a total of 876 cases were recorded.[18] His situation indicates that resolution through non-litigation channels, including mediation, still harbors various issues that make it difficult to maximize its potential as a preliminary dispute resolution mechanism at the company level.

Based on the description above, and concerning the existing characteristics of industrial relations in Indonesia, the analysis of data and field research indicates that Termination of Employment (PHK) Disputes and Rights Disputes are the two types of disputes that currently dominate industrial relations conflict in Indonesia. A similar condition is observed in the tourism sector, which is also predominantly affected by the same types of disputes. The overlapping nature of these two dispute types, combined with the highly dynamic Indonesian labor environment where the regulatory standing of the parties (employees and employers) remains unequal, implies a potential increase in both the quantity and complexity (quality) of disputes, including those in the tourism sector as a continuously growing part of the business world.

2.Institutional Regulation of Industrial Relations Mediation: The Perspective of the UU PPHI

The Industrial Relations Dispute Settlement Law (UU PPHI), as the formal law for industrial dispute resolution, stipulates that if bipartite negotiation fails, one or both parties must register the dispute with the local agency responsible for manpower/labor affairs, attaching proof that attempts at resolution through bipartite negotiation have been made. After receiving the registration from one or both parties, the local labor agency is obligated to offer the parties the option to agree on a resolution through conciliation or arbitration. If the parties fail to make a choice for resolution through conciliation or arbitration within 7 (seven) working days, the labor agency shall delegate the dispute resolution to a mediator, covering all four types of disputes.

The three stages mentioned above are in accordance with the provisions of Article 6, paragraph (1) of Law No. 30 of 1999 concerning Arbitration and Alternative Dispute Resolution (UU ADR)[19], which stipulates that civil disputes or differences of opinion may be resolved by the parties through alternative dispute resolution based on good faith.[20] In the industrial relations dispute settlement system, these stages are known as the tripartite mechanism, involving a third party outside of the disputing parties. This tripartite resolution mechanism constitutes the structure of the Indonesian labor system, involving the government or a third party that is required to be protective and supportive.[21] This is crucial because the parties in these industrial relations disputes have unequal positions: the employee is identified with a weak position, while the employer is identified with a stronger social and economic position, with the worker depending on the employer for income to meet their living needs.[22] This situation is thus philosophically intended to be safeguarded by the characteristic presence of a third party in dispute resolution through the tripartite mechanism.

The Tripartite Mechanism under the Industrial Relations Dispute Settlement Law (UU PPHI) is regulated in several related provisions, including: Resolution through Mediation (Articles 8 to 16), Resolution through Conciliation (Articles 17 to 28), and Resolution through Arbitration (Articles 29 to 54). In addition to the UU PPHI, the tripartite mechanism via mediation is specifically regulated through Minister of Manpower and Transmigration Regulation No. 17 of 2014 concerning the Appointment and Dismissal of Industrial Relations Mediators and Mediation Procedures.[23] The tripartite mechanism via conciliation is specifically regulated through the Minister of Manpower and Transmigration Regulation No. PER.10/MEN/V/2005 concerning the Appointment and Dismissal of Conciliators and Conciliation Procedures.[24]

The following section will outline some of the weaknesses in the current industrial relations dispute settlement regulations applicable in Indonesia, referencing the UU PPHI and its related implementing regulations. This discussion will specifically focus on the mediation mechanism as the second (subsequent) stage that the parties may pursue in an industrial relations dispute after bipartite negotiation has been declared a failure.

a)Definition (Meaning) of Industrial Relations Mediation

Article 1 point 11 of the Industrial Relations Dispute Settlement Law (UU PPHI) stipulates that Industrial Relations Mediation, hereinafter referred to as mediation, is the resolution of disputes of rights, disputes of interest, disputes over termination of employment, and disputes between labor unions/trade unions within only one company through deliberation facilitated by one or more neutral mediators. Furthermore, Article 1 point 12 of the UU PPHI stipulates that an Industrial Relations Mediator, hereinafter referred to as the mediator, is a government employee of the agency responsible for manpower/labor affairs who meets the requirements to be a mediator established by the Minister, whose duty is to conduct mediation and has the obligation to provide a written recommendation to the disputing parties to resolve disputes of rights, disputes of interest, disputes over termination of employment, and disputes between labor unions/trade unions within only one company. Based on these regulations, the operational definition of mediation and industrial relations mediators in the UU PPHI emphasizes the resolution of disputes through deliberation facilitated by a neutral third party who must be a government employee in the field of manpower, meets the mediator’s requirements, and has the obligation to provide a written recommendation to the disputing parties. The emphasis on the mediator being (limited to) a government employee in the manpower sector and their obligation to provide a written recommendation without strong binding power results in the institutional role of the mediator being weakened.

b)The Status of the Recommendation in Industrial Relations Mediation

Referring to the provisions of Article 13 of the Industrial Relations Dispute Settlement Law (UU PPHI), it is stipulated that:

If a settlement agreement for the industrial relations dispute is not reached through mediation, then:

- The mediator issues a written recommendation;

- The written recommendation referred to in letter a must be submitted to the parties within a maximum period of 10 (ten) working days from the first mediation session;

- The parties must have provided a written response to the mediator, stating whether they agree or reject the written recommendation, within a maximum period of 10 (ten) working days after receiving the written recommendation;

- The party that does not provide its opinion, as referred to in letter c, is deemed to reject the written recommendation;

- if the parties agree to the written recommendation as referred to in letter a, then within a maximum period of 3 (three) working days from the date the written recommendation is agreed upon, the mediator must have finished assisting the parties in drafting a Joint Agreement (Perjanjian Bersama) to be subsequently registered at the Industrial Relations Court within the District Court in the jurisdiction where the parties entered into the Joint Agreement, to obtain a certificate of registration.

Furthermore, Article 14 paragraph (1) of the UU PPHI stipulates that: “If the written recommendation as referred to in Article 13 paragraph (2) letter a is rejected by one or both parties, then the parties or one of the parties may continue the dispute resolution to the local Industrial Relations Court at the District Court”.

The regulation concerning the mediator’s obligation to issue a written recommendation when no agreement is reached, without being accompanied by a regulation regarding the binding power of the recommendation, results in the parties (especially the party in the strong position) treating/using the recommendation merely as a formality so that the dispute resolution can then be escalated to the Industrial Relations Court. The party in the weak position (the employee) is disadvantaged both technically and in terms of the increasingly lengthy time required for dispute resolution.

c)Regulation of Mediator Duties

Based on the provisions of Article 6 of Minister of Manpower and Transmigration Regulation No. 17 of 2014 (Permenakertrans No. 17/2014), the Mediator is tasked with:

- Fostering industrial relations;

- Developing industrial relations; and

- Settling Industrial Relations Disputes out of court.

In carrying out their duties, especially in the out-of-court settlement of industrial relations disputes through mediation, cooperation with the Labor Inspector (Pengawas Ketenagakerjaan) is highly necessary, so the institutional relationship between the mediator and the labor inspector in dispute resolution needs to be strengthened (not limited to mere coordination).

d)Regulation of Mediator Obligations

Based on the provisions of Article 8 of Permenakertrans No. 17/2014, the Mediator has the following obligations in resolving Industrial Relations Disputes:

- To request the parties to negotiate before the Mediation process is carried out

- To summon the disputing parties:

- To lead and regulate the course of the Mediation session;

- To assist the parties in drafting a Joint Agreement, if an agreement is reached;

- To issue a written recommendation, if an agreement is not reached;

- To create minutes of the Industrial Relations Dispute settlement;

- To maintain the confidentiality of all information obtained;

- To prepare a report on the results of the Industrial Relations Dispute settlement to the Director General or the Head of the Provincial Agency, or the Head of the relevant Regency/City Agency; and

- To record the results of the Industrial Relations Dispute settlement in the Industrial Relations Dispute registration book.

Regarding the mediator’s obligations, reinforcement is needed so that the mediator is obliged to facilitate and encourage the Parties to explore and uncover their interests, seek the best settlement options for the Parties, and work together to settle.

e)Regulation of Mediator Posts and Jurisdiction

Based on the provisions of Article 11 of Minister of Manpower and Transmigration Regulation No. 17 of 2014 (Permenakertrans No. 17/2014), the Mediator is posted at the: a. Ministry; b. Provincial Agency (Dinas Provinsi); c. Regency/City Agency (Dinas Kabupaten/Kota).

Furthermore, Article 12 of Permenakertrans No. 17/2014 stipulates that:

(1) The Mediator posted at the Ministry, as referred to in Article 11 letter a, is authorized to:

a. Conduct Mediation for Industrial Relations Disputes that occur in more than 1 (one) provincial territory; and

b. Provide technical assistance, supervision, and monitoring of Industrial Relations Dispute settlement carried out by Mediators at the Provincial Agency and/or Regency/City Agency.

(2) The Mediator posted at the Provincial Agency, as referred to in Article 11 letter b, is authorized to:

a. Conduct Mediation for Industrial Relations Disputes that occur in more than 1 (one) regency/city within 1 (one) province;

b. Conduct Mediation for Industrial Relations Disputes delegated by the Ministry or Regency/City Agency;

c. Conduct Mediation for Industrial Relations Disputes at the request of a Regency/City Agency that does not have a Mediator; and

d. Provide technical assistance, supervision, and monitoring of Industrial Relations Dispute settlement carried out by Mediators at the Regency/City Agency.

(3) The Mediator posted at the Regency/City Agency, as referred to in Article 11 letter c, is authorized to:

a. Conduct Mediation for Industrial Relations Disputes that occur in the relevant regency/city;

b. Conduct Mediation for Industrial Relations Disputes delegated by the Ministry or Provincial Agency.

The regulation regarding the placement of mediators at the Ministry, Provincial Agency, and Regency/City Agency, each with its respective authority, without regulating the proportional number of mediators in each region (regency), implies difficulties for employees when a dispute occurs. This is particularly true when a Regency/City Agency does not have a mediator, leading to the case being transferred to the Provincial Agency (where the provincial capital may be far from the regency/city where the dispute occurred). These various regulations indicate that there are weak points in the institutional and procedural formulation of industrial relations mediation as one of the resolution options between employees and employers, in reference to the currently applicable UU PPHI as the formal law.

3.Legal Framework for Strengthening Institutional Mediation in Industrial Relations Dispute Settlement in the Tourism Sector in the Future

Based on the discussion in the previous sub-chapter, there are various regulatory weaknesses that consequently imply an imbalance in the position of the parties, particularly for workers, which this study attempts to counterbalance through the Tripartite Equity Model, a component of the IRS Equity Model. The following is an elaboration of the formulation of the principle of balance in regulating the position of the parties, particularly the worker, in the tripartite mechanism, as formulated through the Tripartite Equity Model.

The following describes several forms of strengthening that can be carried out on mediation institutions with a focus on efforts to provide dispute resolution mechanisms that are able to place both workers and employers in a balanced position. The forms of strengthening mediation institutions referred to include the following:

a)Regulation Regarding The Good Faith of the Parties in Mediation Implementation

Based on the analysis of industrial relations cases and supported by empirical research, the weakness in regulating the mediation stage within the tripartite industrial relations dispute settlement mechanism lies in the lack of good faith from the parties, especially the party with the dominant position, in maximizing mediation as a dispute settlement mechanism. This consequently implies the difficulty of mediation being implemented in accordance with the procedures and provisions regulated in the legislation. Conceptually, mediation is a “good faith” procedure where the disputing parties submit suggestions on how the mediator can resolve the dispute, since they are unable to do so themselves.[25] In contract law, good faith emphasizes honesty in achieving a common goal, which must be upheld by the parties.[26]

The UU PPHI does not specifically regulate the absence of parties and the legal consequences if a party fails to act in good faith during mediation. However, Article 13 paragraph (1) point b of Permenakertrans 17 of 2014 regulates the mediator’s work procedures, one of which is: preparing a written summons for the parties to attend, with due consideration of the timing, so that the Mediation session can be held no later than 7 (seven) working days from receiving the delegation of duties to settle the dispute. Furthermore, paragraph (3) stipulates that if the applicant party that registered the dispute fails to attend after being duly and properly summoned 3 (three) times, the Industrial Relations Dispute registration shall be deleted from the dispute registration book. Paragraph (4) stipulates that if the respondent party fails to attend after being duly and properly summoned 3 (three) times, the Mediator shall issue a written recommendation based on the existing data.

This condition creates the potential for the party in the stronger position (the company), with unlimited access to capital and resources, to ignore this stage due to weak regulation or to treat it merely as a formality to be completed before the dispute is eventually channeled for resolution through the Industrial Relations Court.

Based on these conditions, it is crucial to regulate the good faith of the parties in carrying out mediation and the legal consequences if the parties fail to act in good faith during mediation. This will strengthen the position of the worker, as the weaker party, when settlement through mediation is chosen after the failure of bipartite negotiation. Based on this, a regulatory formulation regarding the good faith of the parties in the UU PPHI is needed, which minimally regulates: The Parties and/or their legal representatives are obliged to pursue mediation with good faith; Matters that can be declared as lack of good faith by the parties or one of the parties in the implementation of mediation; and the legal consequences if the parties or one of the parties fails to act in good faith in the implementation of mediation. In the context of the absence of one party in the mediation process, it is important to note that the information provided by the party that attends in good faith becomes information deemed correct by the mediator and is placed as a determining element in drafting the mediator’s recommendation.

Regulating the good faith of the parties in the implementation of mediation will imply institutional strengthening in the regulation of industrial relations mediation. By regulating the good faith of the parties in mediation, it is expected to be able to balance the positions of the parties and prevent certain conditions, such as negligence or the perception of formality, which were previously potentially exploited by the party in the stronger position.

b)Strengthening the Status of The Industrial Relations Mediator’s Recommendation

Article 13 paragraph (2) of the UU PPHI stipulates that if an agreement for the settlement of the industrial relations dispute is not reached through mediation, then:

a. The mediator shall issue a written recommendation;

b. The written recommendation referred to in letter a must be delivered to the parties no later than 10 (ten) working days from the first mediation session;

c. The parties must provide a written response to the mediator, stating whether they agree or reject the written recommendation, no later than 10 (ten) working days after receiving the written recommendation;

d. The party that does not provide its opinion as referred to in letter c shall be deemed to reject the written recommendation;

e. If the parties agree to the written recommendation referred to in letter a, then no later than 3 (three) working days from the date the written recommendation is approved, the mediator must complete assisting the parties in creating a Joint Agreement, which is then registered at the Industrial Relations Court within the District Court in the legal area where the parties executed the Joint Agreement, to obtain a certificate of registration.

Furthermore, Article 14 paragraph (1) of the UU PPHI stipulates that: “if the written recommendation referred to in Article 13 paragraph (2) letter a is rejected by one or both parties, then the parties or one of the parties may continue the dispute settlement to the Industrial Relations Court within the local District Court”.

The regulation in Article 13 paragraph (2) of the UU PPHI was subsequently deemed not to provide legal certainty, leading to a judicial review by five workers before the Constitutional Court. The Constitutional Court (MK), in its Decision Number 68/PUU-XIII/2015[27], granted the judicial review of Law Number 2 of 2004 concerning the Industrial Relations Dispute Settlement (UU PPHI). The decision mandates that mediators assisting in industrial relations dispute settlement must issue a record of the mediation results (risalah hasil mediasi). According to the Constitutional Court, Article 13 paragraph (2) letter a of the UU PPHI does not provide legal certainty. “The article a quo does not provide fair legal guarantee, protection, and certainty, as well as equal treatment before the law for the Applicants as guaranteed in Article 28D paragraph (1) of the 1945 Constitution”.[28] Therefore, the phrase “written recommendation” in Article 13 paragraph (2) letter a of the UU PPHI is contradictory to the 1945 Constitution, unless interpreted as: “if an agreement for the settlement of the industrial relations dispute is not reached through mediation, the mediator shall issue a written recommendation in the form of a record of settlement through mediation”.

Based on the description above, the issue of legal uncertainty regarding the phrase “written recommendation” in the UU PPHI has been clarified through the Constitutional Court Decision, providing a clearer meaning related to the fulfillment of the formal requirements for filing a lawsuit to the Industrial Relations Court, namely by including the written recommendation in the form of a mediation record. Indirectly, this change in terminology has two different functions: on one hand, it serves as a formal requirement for filing a lawsuit in the Industrial Relations Court, and on the other hand, it can be utilized to institutionally strengthen the status of the mediation results.

Based on the description above, the issue of legal uncertainty regarding the phrase “written recommendation” in the UU PPHI has been clarified through the Constitutional Court Decision, providing a clearer meaning related to the fulfillment of the formal requirements for filing a lawsuit to the Industrial Relations Court, namely by including the written recommendation in the form of a mediation record. Indirectly, this change in terminology has two different functions: on one hand, it serves as a formal requirement for filing a lawsuit in the Industrial Relations Court, and on the other hand, it can be utilized to institutionally strengthen the status of the mediation results.

If analyzed more deeply, the regulation of the legal status of the recommendation as a product of mediation still shows a weakness when one party refuses to implement it. The party in the stronger position tends not to follow the recommendation or even treats it as a formality requirement to be met before taking the dispute to the Industrial Relations Court (PHI). Therefore, it is necessary to strengthen the regulation of this product of mediation (recommendation), especially when mediation fails, and the parties reject the mediator’s recommendation.

The clarification of the recommendation’s terminology in the form of a mediation record as a requirement for fulfilling formal prerequisites, as stipulated in the Constitutional Court Decision, can be utilized institutionally to strengthen the status of the mediator’s recommendation in industrial relations dispute settlement. The mediation record, which is a prerequisite under the UU PPHI for filing a lawsuit against the PHI, should not just be a formality (vide Article 14 paragraph (1) UU PPHI). It should be one of the factors considered by the judge in deciding the case. This is crucial because strengthening the regulation regarding the legal status of the written recommendation in the form of a record will institutionally strengthen the dispute settlement process. Through this regulation, the disputing parties are expected to view the recommendation not merely as a prerequisite to proceed to court, but as a material element for the panel of judges to consider when the dispute enters the litigation stage.

This is important because strengthening the regulations regarding the legal standing of written recommendations in the form of minutes in the settlement of industrial relations disputes through mediation will strengthen mediation as an institutional dispute resolution mechanism. The formulation in the PPHI Law, which stipulates that the minutes of mediation results from industrial relations mediators are one of the considerations of the panel of judges in making decisions, is one form of strengthening the standing of the results of settlements through mediation in the settlement of industrial relations disputes. Through this regulation, it is hoped that the disputing parties will consider recommendations in the form of mediation minutes not only as a formality for proceeding to court, but also become one of the considerations for the panel of judges in deciding when the dispute enters the litigation stage in the Industrial Relations Court.

c)Strengthening Regulations Regarding Mediator Obligations

Article 9 of Ministerial Regulation No.17 of 2014 stipulates that a Mediator in resolving Industrial Relations Disputes has the following obligations:

Ketentuan Pasal 9 Permenakertrans 17 Tahun 2014 mengatur bahwa Mediator dalam menyelesaikan Perselisihan Hubungan Industrial mempunyai kewajiban:

a. To request that the parties negotiate before the Mediation process is carried out;

b. To summon the disputing parties;

c. To lead and manage the Mediation session;

d. To assist the parties in drafting a collective agreement, if an agreement is reached;

e. To make written recommendations, if an agreement cannot be reached;

f. To prepare minutes of the Industrial Relations Dispute resolution;

g. To maintain the confidentiality of all information obtained;

h. To report the results of the Industrial Relations Dispute resolution to the Director General or the Head of the Provincial Office, or the Head of the Regency/City Office concerned; and

i. To record the results of the Industrial Relations Dispute resolution in the Industrial Relations Dispute registration book.

The stipulations concerning the Mediator’s obligations in the Ministry of Manpower and Transmigration Regulation (Permenakertrans), as outlined above, require several regulatory enhancements in an effort to strengthen mediation (the position of the mediator) institutionally in the process of resolving industrial relations disputes. Enhancements to the regulation of obligations that can be implemented include:

a. Clarifying the rights and obligations of the Parties in accordance with the prevailing laws and regulations;

b. Tracing and exploring the interests of the Parties; and

c. Seeking various best resolution options for the Parties;

d. Facilitating and encouraging the Parties to cooperate in the dispute resolution.

Based on the results of field research through interviews with industrial relations mediators, several forms of the above enhancements will open up opportunities for the mediator to be more active in facilitating the dispute resolution process between the parties (while maintaining neutrality), particularly in efforts to help the parties resolve their dispute by maximizing agreements that prioritize a win-win solution.

d)Strengthening The Regulation Related to Mediator Authority

Article 10 of Permenakertrans No. 17 of 2014 regulates the mediator’s authority, which includes:

(1) The Mediator in resolving Industrial Relations Disputes has the authority to:

a. Request the parties to provide verbal and written statements

b. Request documents and letters related to the dispute from the parties;

c. Present witnesses or expert witnesses in Mediation if necessary;

d. Request necessary documents and letters from the Provincial Office or Regency/City Office, or related institutions; and

e. Reject the power of attorney of the disputing parties if they do not possess a specific power of attorney.

(2) In addition to the authorities referred to in paragraph (1), the Mediator is authorized to reject the parties and/or holders of the power of attorney if there is an indication of hindering the Mediation process.

(3) The Mediator, before conducting the Mediation process, can invite the disputing parties for clarification of the problem or Industrial Relations Dispute faced by the parties.

(4) The clarification, as referred to in paragraph (3) is carried out to obtain information and/or complete dispute data from the parties, the results of which are recorded in the clarification minutes.

The regulation of the Mediator’s authority as stipulated above still provides an opening for the parties, especially the employers, to leverage their strong position when participating in mediation as a dispute resolution option. There is a need for regulation concerning the mediator’s authority to determine that a party or one of the parties is not acting in good faith in the implementation of mediation, along with the legal consequences that arise when the parties or one of the parties lacks good faith. Furthermore, based on several current field conditions, it is also important to strengthen the regulation regarding the mediator’s authority to directly request documents from the company, along with the legal consequences for companies that are unwilling to submit data or documents related to the dispute, as well as the regulation of the mediator’s authority to be able to collaborate with other related industrial relations institutions in the context of resolving the dispute.

e)Regulation of The Position and Availability of Industrial Relations Mediators in the Nearest Company

Territory Article 11 of Permenakertrans No. 17 of 2014 stipulates that the Mediator is located at:

a. The Ministry;

b. The Provincial Office;

c. The Regency/City Office.

Article 12 of the Permenakertrans then regulates that:

(1) A Mediator located at the Ministry, as referred to in Article 11 letter a, is authorized to:

a. Conduct Mediation for Industrial Relations Disputes occurring in more than 1 (one) provincial area; and

b. Provide technical assistance, supervision, and monitoring of the resolution of Industrial Relations Disputes carried out by Mediators at the Provincial Office and/or Regency/City Office.

(2) The mediator located at the Provincial Office as referred to in Article 11 letter b, is authorized to:

a. Conduct Mediation for Industrial Relations Disputes occurring in more than 1 (one) regency/city within 1 (one) province;

b. Mediation for Industrial Relations Disputes upon delegation from the Ministry or the Regency/City Office;

c. Conduct Mediation for Industrial Relations Disputes upon request from a Regency/City Office that does not have a Mediator; and

d. Provide technical assistance, supervision, and monitoring of the resolution of Industrial Relations Disputes carried out by Mediators at the Regency/City Office.

(3) A Mediator located at the Regency/City Office, as referred to in Article 11 letter c, is authorized to:

a. Conduct Mediation for Industrial Relations Disputes occurring in the relevant regency/city;

b. Conduct Mediation for Industrial Relations Disputes upon delegation from the Ministry or the Provincial Office.

The regulation of the mediator’s position at the Ministry, Provincial Office, and Regency/City Office, each with their respective authorities, without regulating the proportionate number of mediators in each region (regency) has implications for difficulties for the worker when a dispute occurs, especially when the Regency/City Office does not have a mediator, thus delegating the case to the Province (the provincial capital is far from the regency/city where the dispute occurred). This needs to be addressed through strengthening the institutionalization of industrial relations mediation, particularly concerning the regulation of the proportionate number of mediators at the Regency/City Office, Provincial Office, and Ministry. This regulation plays an important role in ensuring the availability of mediators in every regency/city so that the parties, especially workers who are generally economically weak, can be helped by the availability of a mediator in the nearest company area, making it more effective and efficient in terms of cost, energy, and time.

f)Regulation of Professional Mediators and Independent Mediation Institutions

In other countries, mediation remains the preferred method of resolution. Similar to Indonesia, which mandates mediation as a compulsory resolution method, other countries like the United States and Singapore also do the same. However, these two countries offer the availability of professional mediators and independent mediation institutions. This is done to add a variety of options so that both workers and employers can choose according to their needs.

In Singapore, for instance, mediators are usually provided by the Minister of Manpower with the assurance that these individuals are long-experienced and neutral. The same applies to the United States with its Federal Mediation and Conciliation Service, which provides similar services. In Indonesia, this ought to be emulated to encourage the trust of the disputing parties in utilizing mediation and avoiding the fairly lengthy litigation process.

Based on the description above, it can be seen that the institutional strengthening of mediation as one of the options for resolving industrial relations disputes in the tripartite mechanism can be achieved by strengthening the regulation related to the good faith of the parties in the execution of mediation, strengthening the regulation related to the mediator’s recommendation, strengthening the regulation related to the mediator’s obligations and authority, strengthening the regulation related to the position and availability of mediators in the nearest company territory, the regulation of professional mediators, and the regulation of independent mediation institutions. Strengthening the mediation institution, with a focus on efforts to balance or equalize the position of the parties, especially workers, is expected to maximize the advantages of mediation as one of the main options in resolving industrial relations disputes, including in resolving disputes that occur in the tourism sector.

Conclusion

The conclusion of this research indicates that Termination of Employment (PHK) disputes and rights disputes currently dominate industrial relations conflicts in Indonesia. According to the latest data from 2024, the number of PHK disputes and disputes ofver rights reached 7,225 cases. This condition is linear with the existing conditions in the tourism sector, which indicates that the disputes that occur are also dominated by the same types of disputes. This condition reflects the imbalance between the spirit of efficiency desired by companies and the fulfillment of workers’ rights. This then gives rise to the potential for an increase in industrial relations disputes within the framework of employment relations, both in terms of quantity and quality. Regarding the dispute resolution mechanism, particularly the regulation of industrial relations mediation, based on an analysis of the Industrial Relations Dispute Settlement Law (UU PPHI), its implementing regulations as formal law for the resolution of industrial relations disputes, and by observing the existing conditions in the practical context of industrial relations dispute resolution currently occurring in Indonesia (particularly in the tourism sector), it was found that workers are still placed in a weak (unbalanced) position when they have to go through the dispute resolution mechanism in the PPHI system. This imbalance of position is also one of the weaknesses when workers use industrial relations mediation as a medium or means of resolving disputes that occur in companies. This study proposes the Mediation Equity Model as a framework to strengthen the legal basis of industrial relations mediation. The model seeks to enhance the position of workers and maximize the inherent advantages of mediation in resolving industrial disputes. It is constructed through the formulation and mapping of regulatory shortcomings, particularly within the Industrial Relations Dispute Settlement Law (UU PPHI), and supported by empirical findings from field research, with a specific focus on mediation practices in the tourism sector.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to all parties who have supported the implementation of this research, particularly the Rector of Udayana University, the Head of the Institute for Research and Community Service (LPPM) of Udayana University, the Dean of the Faculty of Law of Udayana University, as well as all other relevant parties, whose contributions have enabled this research to be carried out smoothly.

References

Scholarly Literature:

Arsalan, H., Putri, D. S. (2020). Reformasi hukum dan hak asasi manusia dalam penyelesaian perselisihan hubungan industrial. Jurnal HAM, 11(1);

Dananjaya, N.S., Sudiarawan, K.A., dkk. (2023). Penerapan keunggulan karakteristik penyelesaian sengketa secara non litigasi dalam penyelesaian perselisihan hubungan industrial. (Laporan Penelitian Hibah Unggulan Udayana). LPPM Universitas Udayana;

Dermawan, F. A., & Sarnawa, B. (2021). Peran Dinas Tenaga Kerja Dalam Proses Mediasi Penyelesaian Permasalahan Hubungan Industrial. Media of Law and Sharia, 2(1), 45–54.

Harianto, A. (2024). Paradigmatic Problems of Industrial Relation Dispute Settlement in the Perspective of Pancasila Industrial Relations. Journal of Law and Legal Reform, 5(1), 27–37.

Hidayat, R. (2023). Kepastian Hukum Putusan Tripartit Dalam Penyelesaian Perselisihan Hubungan Industrial Berdasarkan Undang-Undang Nomor 2 Tahun 2004 Tentang Penyelesaian Perselisihan Hubungan Industrial. Dalam SeNaSPU: Seminar Nasional Sekolah Pascasarjana (Vol. 1, No. 1, hlm. 177);

Irawan, N. (2023). Studi Yuridis Normatif Implementasi Regulasi Perselisihan Hubungan Industrial. Jurnal Ketenagakerjaan, 18(1);

Karsona, A. M., Putri, S. A., Mulyati, E., Kartikasari, R. (2020). Perspektif penyelesaian sengketa ketenagakerjaan melalui Pengadilan Hubungan Industrial dalam menghadapi Masyarakat Ekonomi ASEAN. Jurnal Poros Hukum Padjadjaran, 1(2);

Kesek, S. (2015). Studi Komparasi Penyelesaian Perselisihan Hubungan Industrial Melalui Mediasi dan Konsiliasi. Dedikasi: Jurnal Ilmiah Sosial, Hukum, Budaya, 31(2);

Mahkamah Konstitusi Republik Indonesia. (2015). MK: Mediator hubungan industrial harus terbitkan risalah mediasi. <https://www.mkri.id/index.php?page=web.Berita&id=12141>;

Mantili, R. (2021). Konsep Penyelesaian Perselisihan Hubungan Industrial Antara Serikat Pekerja dengan Perusahaan Melalui Combined Process (Med-Arbitrase). Jurnal Bina Mulia Hukum, 6(1);

Safrida, S., Kamello, T., Purba, H., Sembiring, R. (2024). Asas Itikad Baik Dalam Perjanjian Kerja Bersama Antara Pengusaha Dengan Serikat Pekerja ditinjau dari Hukum Perjanjian. Inspiring Law Journal, 2(1);

Sari, A. A., Dewi, A. A., Arthanaya, I. W. (2021). Perlindungan hukum karyawan terkait pengurangan gaji akibat pandemi Covid-19 pada hotel dan restaurant di area Seminyak. Jurnal Analogi Hukum, 3(3);

Sellang, K., Ahmad, J., Mustanir, A. (2022). Strategi dalam peningkatan kualitas pelayanan publik: Dimensi, konsep, indikator dan implementasinya. Qiara Media;

Sudiarawan, K. A., Martana, P. A. (2019). Implikasi hukum pengaturan upah minimum sektoral Kabupaten Badung terhadap pelaku usaha pada sektor kepariwisataan di Kabupaten Badung Provinsi Bali. Supremasi Hukum: Jurnal Penelitian Hukum, 28(1).

Normative Acts:

Indonesia. (2004). Law Number 2 of 2004 concerning The Settlement of Industrial Relations Disputes. Government of Indonesia.

Indonesia. (1999). Law Number 30 of 1999 on Arbitration and Alternative Dispute Resolution. Government of Indonesia.

Ministry of Manpower and Transmigration of the Republic of Indonesia. (2014). Regulation No. 17 of 2014 on the Appointment and Dismissal of Industrial Relations Mediators and Mediation Procedures. Government of Indonesia

Ministry of Manpower and Transmigration of the Republic of Indonesia. (2005). Regulation PER.10/MEN/V/2005 on the Appointment and Dismissal of Conciliators and Conciliation Procedures. Government of Indonesia.

Constitutional Court of the Republic of Indonesia. (2015). Decision No. 68/PUU-XIII/2015 on the Judicial Review of Law No. 2 of 2004 concerning the Settlement of Industrial Relations Disputes. Retrieved from https://www.mkri.id/

Court Decisions:

Direktori Putusan Mahkamah Agung. (2020).

Direktori Putusan Mahkamah Agung. (2021).

Direktori Putusan Mahkamah Agung. (2022). https://putusan3.mahkamahagung.go.id/direktori/index/pengadilan/mahkamah-agung/kategori/phi/tahunjenis/putus/tahun/2022.html

Direktori Putusan Mahkamah Agung. (2023). https://putusan3.mahkamahagung.go.id/direktori/index/pengadilan/mahkamah-agung/kategori/phi/tahunjenis/putus/tahun/2023.html

Direktori Putusan Mahkamah Agung. (2024).

Other Supporting Materials:

Databoks. (2023). Ini Banyaknya Perselisihan Hubungan Industrial di Indonesia pada 2023. https://databoks.katadata.co.id/datapublish/2024/03/20/ini-banyaknya-perselisihan-hubungan-industrial-di-indonesia-pada-2023.

Footnotes

[1] Sudiarawan, K. A., Martana, P. A. (2019). Implikasi hukum pengaturan upah minimum sektoral Kabupaten Badung terhadap pelaku usaha pada sektor kepariwisataan di Kabupaten Badung Provinsi Bali. Supremasi Hukum: Jurnal Penelitian Hukum, 28(1), 33-56.

[2] Sari, A. A., Dewi, A. A., Arthanaya, I. W. (2021). Perlindungan hukum karyawan terkait pengurangan gaji akibat pandemi Covid-19 pada hotel dan restaurant di area Seminyak. Jurnal Analogi Hukum, 3(3), 382-387.

[3] Sellang, K., Ahmad, J., Mustanir, A. (2022). Strategi dalam peningkatan kualitas pelayanan publik: Dimensi, konsep, indikator dan implementasinya. Qiara Media, 12.

[4] Indonesia. (2004). Law Number 2 of 2004 concerning The Settlement of Industrial Relations Disputes. Government of Indonesia.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Arsalan, H., Putri, D. S. (2020). Reformasi hukum dan hak asasi manusia dalam penyelesaian perselisihan hubungan industrial. Jurnal HAM, 11(1), 39-49.

[7] Harianto, A. (2024). Paradigmatic Problems of Industrial Relation Dispute Settlement in the Perspective of Pancasila Industrial Relations. Journal of Law and Legal Reform, 5(1), 27–37.

[8] Mantili, R. (2021). Konsep Penyelesaian Perselisihan Hubungan Industrial Antara Serikat Pekerja dengan Perusahaan Melalui Combined Process (Med-Arbitrase). Jurnal Bina Mulia Hukum, 6(1), 1-12.

[9] Dermawan, F. A., & Sarnawa, B. (2021). Peran Dinas Tenaga Kerja Dalam Proses Mediasi Penyelesaian Permasalahan Hubungan Industrial. Media of Law and Sharia, 2(1), 45–54.

[10] Arsalan, Op. Cit.

[11] Karsona, A. M., Putri, S. A., Mulyati, E., Kartikasari, R. (2020). Perspektif penyelesaian sengketa ketenagakerjaan melalui Pengadilan Hubungan Industrial dalam menghadapi Masyarakat Ekonomi ASEAN. Jurnal Poros Hukum Padjadjaran, 1(2), 158-168.

[12] Dananjaya, N.S., Sudiarawan, K.A., dkk. (2023). Penerapan keunggulan karakteristik penyelesaian sengketa secara non litigasi dalam penyelesaian perselisihan hubungan industrial. (Laporan Penelitian Hibah Unggulan Udayana). LPPM Universitas Udayana.

[13] Databoks. (2023). Ini Banyaknya Perselisihan Hubungan Industrial di Indonesia pada 2023. <https://databoks.katadata.co.id/datapublish/2024/03/20/ini-banyaknya-perselisihan-hubungan-industrial-di-indonesia-pada-2023> (Last access: November 15, 2024).

[14] Direktori Putusan Mahkamah Agung. (2020). https://putusan3.mahkamahagung.go.id/direktori/index/pengadilan/mahkamah-agung/kategori/phi/tahunjenis/putus/tahun/2020.html.

[15] Ibid. (2021). https://putusan3.mahkamahagung.go.id/direktori/index/pengadilan/mahkamah-agung/kategori/phi/tahunjenis/putus/tahun/2021.html.

[16] Ibid. (2022). https://putusan3.mahkamahagung.go.id/direktori/index/pengadilan/mahkamah-agung/kategori/phi/tahunjenis/putus/tahun/2022.html.

[17] Ibid. (2023). https://putusan3.mahkamahagung.go.id/direktori/index/pengadilan/mahkamah-agung/kategori/phi/tahunjenis/putus/tahun/2023.html.

[18] Ibid. (2024). https://putusan3.mahkamahagung.go.id/direktori/index/pengadilan/mahkamah-agung/kategori/phi/tahunjenis/putus/tahun/2024.html

[19] Indonesia. (1999). Law Number 30 of 1999 on Arbitration and Alternative Dispute Resolution. Government of Indonesia.

[20] Irawan, N. (2023). Studi Yuridis Normatif Implementasi Regulasi Perselisihan Hubungan Industrial. Jurnal Ketenagakerjaan, 18(1), 49.

[21] Hidayat, R. (2023). Kepastian Hukum Putusan Tripartit Dalam Penyelesaian Perselisihan Hubungan Industrial Berdasarkan Undang-Undang Nomor 2 Tahun 2004 Tentang Penyelesaian Perselisihan Hubungan Industrial. Dalam SeNaSPU: Seminar Nasional Sekolah Pascasarjana (Vol. 1, No. 1, hlm. 177).

[22] Irawan, N. op.cit.

[23] Ministry of Manpower and Transmigration of the Republic of Indonesia. (2014). Regulation No. 17 of 2014 on the Appointment and Dismissal of Industrial Relations Mediators and Mediation Procedures. Government of Indonesia

[24] Ministry of Manpower and Transmigration of the Republic of Indonesia. (2005). Regulation PER.10/MEN/V/2005 on the Appointment and Dismissal of Conciliators and Conciliation Procedures. Government of Indonesia.

[25] Kesek, S. (2015). Studi Komparasi Penyelesaian Perselisihan Hubungan Industrial Melalui Mediasi dan Konsiliasi. Dedikasi: Jurnal Ilmiah Sosial, Hukum, Budaya, 31(2), 133.

[26] Safrida, S., Kamello, T., Purba, H., Sembiring, R. (2024). Asas Itikad Baik Dalam Perjanjian Kerja Bersama Antara Pengusaha Dengan Serikat Pekerja ditinjau dari Hukum Perjanjian. Inspiring Law Journal, 2(1), 59.

[27]Constitutional Court of the Republic of Indonesia. (2015). Decision No. 68/PUU-XIII/2015 on the Judicial Review of Law No. 2 of 2004 concerning the Settlement of Industrial Relations Disputes. Retrieved from https://www.mkri.id/.

[28] Mahkamah Konstitusi Republik Indonesia. (2015). MK: Mediator hubungan industrial harus terbitkan risalah mediasi. https://www.mkri.id/index.php?page=web.Berita&id=12141.

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4708-1701

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4708-1701