The Changes in Drug Laws to Apply the Death Penalty for Drug-Related Offences in Vietnam

##plugins.themes.bootstrap3.article.main##

Abstract

Vietnam has a history of executing individuals for particularly serious crimes. Applying the death penalty for drug-related crimes has sparked considerable debate since the first criminal code in 1985. Vietnam has retained this toughest punishment as one of the deterrent methods to combat drug trafficking in the last three decades. However, as a retentionist-and-reductionist state, Vietnam abolished capital punishment for several crimes in the last code (2015), including drug possession and appropriation. The application of the death penalty for drug offences in Vietnam has evolved in response to international standards and the country’s global integration. Despite these changes, the death penalty remains a contentious issue in Vietnam, with the country maintaining its right to use it in its criminal code system. The path towards the complete abolition of capital punishment for drug offences is still uncertain because this complex issue involves political, legal, and social aspects in Vietnam’s context, particularly when the Communist Party’s ideologies still prefer a supply-driven reduction. This study uses personal reflections from over 20 years to focus and combine with the grey literature from national reports and desk-study in Vietnam’s legislative documents. Seven specific thoughts with relevant recommendations in the last section will explain why we should need further evidence to (re)call for consideration to reduce the death penalty for drug offences before requesting/asking Vietnam to abolish these concerns immediately.

Keywords: Drug-related offences, capital punishment, crime policy, Vietnam.

Introduction

Law and punishment have existed in Vietnam to prevent and combat crimes and ensure national security and social order. Since the implementation of the Renovation Period (Đổi Mới in Vietnamese) in the middle of the 1980s, particularly after Vietnam released a new Constitutional vision (1992), increasing attention has been given to capital punishment in Vietnam. In Vietnam, the information and data about the death penalty have been limited strictly and unpublished officially by media communication caused by legal matters and political attitudes.[1] Particularly, it is tough for foreigners to obtain valid and reliable data to assess the practical application and executions in Vietnam.[2] Vietnamese researchers can understand and collect the data through their native language pathways, but it is still unclassified, and even ‘they are very wary…and fear reprisals for investigating.’[3] Besides that, Vietnamese scholars are often self-conscious about assessing the death penalty’s policies and executions as objectively as possible.[4] To a lesser extent, they only share this information at national events with the official permission of authorities to avoid trouble because Vietnam had classified all court documents, records, and reports on the death penalty as belonging to the ‘extremely secret level’ since the 2000s.

Alongside implementing the economic reform within the scope of the Renovation Period (Doi Moi in Vietnamese) in the 1980s, the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV) has been committed to updating and adjusting its legal norms and perspectives in punitive applications. The Criminal Code of Vietnam (CCV) was published in 1985 as the first official legal document in criminal law’s field after Vietnam’s war reunification. The death penalty is classified as one of the six principal sentences in the Vietnamese punishment system, including warning, fine, non-custodial reform, termed imprisonment, life imprisonment, and the death penalty. It is prescribed in regulations as 29 separate articles at seven independent chapters, accounting for 14.89% of the total 195 offences, but did not apply to drug-related crimes. Specific conditions, scopes and subjects of application of the death penalty are also stipulated. Accordingly, the death penalty is only available for offenders in particularly serious cases such as violation of national security; crime against peace; crime against humanity; war crime; socialist property violation; violation of human dignities such as health violation, murder and rape. However, this toughest punishment is not applicable for youth offenders and pregnant women or when the offender is tried, meanwhile suspending the execution of those pregnant or women taking care of their children under 12 months old.[5]

Based on society’s distinct conditions and cultural backgrounds, the 1985 CCV has been amended four times to respond to the increasingly demanding requirements of Vietnam’s society after Đổi Mới. The first time was on 28 December 1989; the amended and supplemented provisions with several articles of the 1985 CCV prescribed four drug offences in Article 96a, and there is a maximum death penalty. Secondly, on 12 August 1991, the law amending and supplementing several articles of the 1985 CCV prescribed the death penalty for other crimes, namely fraud, misappropriating socialist assets (Article 134); fraud appropriating the private property of citizens (Article 157); bribery (Article 226). Thirdly, on 22 December 1992, Vietnam’s government continued to amend and supplement to apply the death penalty for smuggling. On 10 May 1997, it has been added the death penalty for six law-prescribed offences in the final adjustment. At the same time, lawmakers split Article 96a into four different types (185b, 185c, 185d, 185đ) and retained the death penalty for this crime. Article 112 stipulates rape is divided into two charges, rape and rape against the child (Article 112A), and also retains the death penalty for this crime.

Notably, in all four amendments and supplement times, the supply and demand for drugs began to increase in Vietnam. To enhance drug control with stricter punishments, the death penalty was codified as the harshest sentence for drug-related offences in article 96a in the First Amendment and supplementation of the 1985 CCV in December 1989.[6] As a result, the fourth amendment of the 1985 CCV expanded capital punishment for drug-related crimes with seven separate articles, among 44 death-sentence articles in 1997, accounting for 20.37% of the total 216 articles. The 1999 CCV, however, narrowed down and clearly defined the scope and conditions of this punishment. In 1997, Vietnam signed all three United Nations Drug Control Conventions to incorporate international drug control standards into domestic law.[7] Consequently, the assessment of particularly serious drug-related crimes, whether punishable by death or life imprisonment, was re-examined and re-regulated. Article 200 of the 1999 CCV, which pertains to forcing and inducing someone to use narcotics illegally, changed the punishment from the death penalty to life imprisonment. The death penalty was also removed for some specific crimes to align with the new requirements of economic, political, social, and international integration. The number of articles prescribing the death penalty was reduced to 29, accounting for 11% of the total 267 articles in the 1999 CCV.

However, while reprieving and commuting could be applied to economic offences (e.g., embezzled property and bribed property), reducing the capital drug-related offences and their related reprieves was not yet implemented as much as possible.[8] Among eight death articles abolished in the 1999 CCV, the illegal organisation for drug use (article 197) passed; meanwhile, the four drug-related activities (stockpiling, transporting, trading, and appropriating) merged into one article in the 1999 CCV (article 194). After over 15 years of implementing the 1999 CCV, many conditions and the scope of applying the death penalty have changed due to various factors, prompting Vietnam’s policymakers to reform this severe punishment towards humanitarian goals. In the latest version of the 2015 CCV and its first amendment in 2017, the reduction of death penalties remained a debated topic among National Assembly delegates. Currently, there are 18 ‘particularly serious crimes’ punishable by death, in which drug trafficking activities have re-separated as similar to the 1985 CCV with four independent articles, but illegal stockpiling and appropriation of narcotics abolished the death penalty. In other words, there are only three drug-related crimes in the latest code (2015) compared to seven in the first code (1985).[9]

In this study, combining grey literature and legislative documents, I will (re)call for further consideration to understand fully why Vietnam still resist the death penalty for drug trafficking activities and how Vietnam should act to reform their current drug laws to reduce it before abolishing. As part of my observations and reflections over twenty years on this topic, this study has continued to remain and support my previous studies and other Vietnamese scholars cited in this paper’s references. It will be analysed after briefing the current drug laws with this punishment in the region compared to Vietnam’s perspectives. In this part, the actuality of the given issue, research topic, established aims, tasks, and stages are emphasised. Structuring the problem and clearly establishing the issue are important.

1. Drug-Related Offences and the Death Penalty in Southeast Asia Region

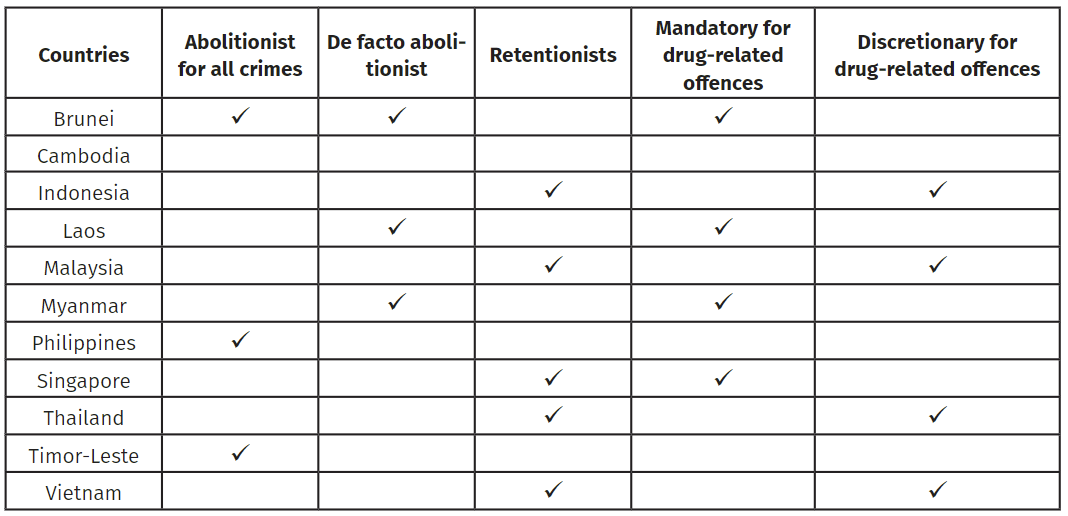

The ongoing movement to abolish the death penalty to uphold the fundamental ‘right to life’ is expected to become a widespread trend soon. Yet, some nations persist in upholding and enforcing capital punishment within their legal systems. Asia is at the heart of the global effort to end the death penalty, which covered over 90% of all executions in the past decades, with a fluctuation in the number of executions in 35 countries, including several Southeast Asian countries.[10] Despite the variety of political, religious, historical, and social systems, it is an irrefutable issue that the region remains many drug-related executions occur.[11] Accordingly, approximately 75% (8 out of 11 countries) impose capital punishment for these most serious crimes in their domestic regulations. Table 1 below shows this region’s different policy perspectives with diverse death penalty applications. Noticeably, while those eight countries argued their applicable punishment for drug-related crimes aligned with the international law (para 2, article 6 ICCPR) to “impose only most serious crimes”, the recent arguments from the United Nations do not support this claim.[12]

Table 1: The death penalty (including drug-related offences) in the Southeast Asian countries.

Those who advocate for maintaining the death penalty for drug-related crimes do so in two main ways. One approach is through mandatory sentences, and the other is by incorporating provisions in criminal law that prescribe the death penalty for certain offences but allow for commutation to life imprisonment. For the former, a mandatory sentencing system automatically imposes the death penalty upon conviction of a crime under their legislative regulations. Singapore, for instance, is a prominent example in Southeast Asia. Under section 17 of the Misuse of Drugs Act, anyone who possesses, consumes, manufactures, imports, exports, or traffics illegal drugs (above a certain amount) will be sentenced to death, regardless of any potential mitigating factors. A national survey revealed that at least one-third of 1,500 Singaporeans aged between 17 and 74 support this issue.[13] For the latter, some states choose to temporarily suspend the death penalty for drug-related offences or seldom carry out executions of those convicted of them based on specific considerations and practical contexts. For instance, while Thailand still officially imposes the death penalty for drug trafficking, only 12 out of 281 potential executions between 1935 and 2001 were for drug-related crimes; executions were even rarer between 2009 and 2018.[14] However, this nine-year hiatus ended in 2018 with at least ten executions, including one for a drug offence by a woman from Myanmar, though the number of executions fell back to zero in 2019. In essence, Thailand is a typical case in Asia of a de facto abolition of executions for drug-related crimes, even though they are still codified in law.

2. Preventing and Combating Drug-Related Offences through Resisting the Strictest Punishments: A Leading Powerpoint of Communist Party and Government

In Vietnam, the Communist Party is ‘the leading force of the State and society… maintains close ties with the People, serves the People, submits to People’s supervision and is accountable to the People in its decisions’ (Para 1 &2, Article 4, the 2013 Constitution). Accordingly, the Party strongly established its position on this issue and ‘brooked no debate or drafting that differed from its views’.[15] As the highest functions, the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV) is central in establishing and controlling law enforcement agencies for ‘protecting national security and social order’ (Article 65, the 2013 Constitution). Dealing with drug concerns, Vietnam has established multiple agencies in their drug control system under the leadership of CPV. Under the CPV’s commission, Directive No.06/CT-TW of the Political Bureau of the Party in 1996 has been considered one of the first official documents to expose the role of the CPV in drug control. This document is requested that:

Taking all measures to prevent drug sources from being brought into Vietnam from abroad, punishing promptly and severely those who produce, traffic, store, organise or force the use of drugs.

In Vietnam, the Party will instrumentalise ‘the Government and its ministries, the legal system, economic life, and social life, masks other strands of thought and action’.[16] Regarding social order, accordingly, preventing and combating drugs are compulsory responses of Party Committees, members and organisations at all levels, in which the drug law enforcement forces are the central bodies.[17] To deploy this requirement, as a core armed force of the CPV, the Ministry of Public Security (MPS) established the first-ever anti-narcotics police forces (ANPF) in 1997 to be responsible for directly advising the CPV, the Government, and the National Committee for AIDS, Drugs and Prostitution Prevention and Control. Accordingly, the MPS’s Decision No.192 determined that:

They (ANPF) carry out professional measures to prevent, detect, fight, and handle all types of drug-related crimes. They directly investigate large, especially complex, drug crimes… contributing to protecting national security and preserving social order and safety.

To support absolutely the ANPF (MPS) in supply reduction, Vietnam passed the first National Action Plan on Preventing and Combating Crimes (known as Program 138). Particularly, the Resolution No.09/1998/NQ-CP, Vietnam also identified that:

Using synchronous measures to promptly and resolutely suppress dangerous crime (e.g., organised crime, drug trafficking, and others). The Ministry of Public Security (MPS) shall preside over and coordinate with relevant ministers and branches to improve and strengthen professional forces to directly prevent and fight against those crimes.

As part of the main duties to implement Project 3 of Program 138 – Fighting and Combating Organised Crimes, Particularly Serious Criminals, and International-related Crimes, ANPF’s main functions, obligations, and responsibilities focus on anticipating, prevent, and combat drug-related crimes, including proposing to amend the 1985 CCV to apply the strictest measures for drug-related offences. Most complex operations have resulted in several deaths for traffickers and their accomplices, as the ANPF’s external officials also observed that.

The number of death sentences has increased rapidly, which can be explained by the fact that the amounts of drugs seized by law enforcement agencies are exceptionally large, many times greater than the minimum amount required to attract a death sentence under the law.[18]

The situation of drug trafficking from the Golden Triangle area pushed the high volume of heroin into Vietnam’s market, which made the rate of drug users and drug-related crimes more severe and threatened social order. To deal with this concern by being influenced and experiencing the model of the Soviet’s sentencing in dealing with criminals, CPV could be ideologised that increasing the severity of punishment can deter drug offences.[19] Therefore, at the fourth amendment of the 1985 CCV, they proposed to apply capital punishment for drug-related crimes with seven separate articles, among 44 death-sentence articles in 1997. By establishing the comprehensive and professional task force (ANPF) in the late 1990s, CPV expected its leading role forever to prevent and combat the war on drugs by applying punitive-based policing to investigate and prosecute any drug dealers with the toughest punishment.

2.1. Rising the Transnational Narcotics Trafficking: Applying the Death Penalty to Respond to the ‘Cat-and-Mouse’ Game

As a transnational hub, the threat of illicit drug resources from outside has continued to explore Vietnam as a valuable and economic target as practically possible in both destination and transit markets. Our grey literature identified that in recent years, drug trafficking has become much more complicated in Southeast Asia, with rapid increases in local consumption linked to growing affluence and social expectations, particularly with synthetic drugs and their diverse types.[20] Geographically, porous borderlands with Cambodia, China and Laos and a long coastline offer advantageous conditions for trafficking illicit drugs into and through Vietnam. In the last reports on trends and patterns of transnational organised crime, UNODC also warned that Vietnam is now exploiting transnational networks to transfer synthetic drugs into third countries and beyond.[21] To respond to it, under requesting of the CPV, the ANPF routinely organises raids and intensively suppresses drug-related crimes as the highest operation in their policing duty. Applying the death penalty for these practically serious crimes is the priority in the policing strategies of ANPF. In other words, punitive-based policing was considered one of the specialised duties of fighting and combating drug offences under the request of the CPV. Some ANPF officials recently shared that.

Drug use and addiction are the fastest pathways to criminal behaviours…. and drug use makes up the highest number of offenders across society…preventing and combating all drug-related crimes are our most prioritised duties: nothing more, nothing less.[22]

Additionally, as a prominent member of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), Vietnam has taken seriously its responsibility to implement regional drug control policies through pre-dominating supply reduction operations to combat drug trafficking. Although Vietnam is facing critical suspicions about the rigid policy to use the death penalty to demonstrate its powerful provision in the war on drugs, retaining this toughest punishment is considered a clear declaration in their drug policy and law.[23] As Luong (2021) argued that

Concern over the situation led to new provisions in counter-narcotics policing in Vietnam, namely, a zero-tolerance measure for any drug trafficking groups/networks... as soon as any organisation grows in size and operation, it will attract attention from the police. The Communist Government will not tolerate the existence of any organised criminal groups.[24]

According to the MPS’ annual report, between 1992 and 2000, the annual crime rate averaged 60,000 cases, of which there are around 11,000 drug-related crimes, approximately 20 per cent.[25] Between 1993 and 2010 (excluding 2003-4 without data), the total number of defendants sentenced to death was 2,600 defendants.[26] Numbers of death row defendants tend to increase in this period, more particularly with the most remarkable growth of drug-related crimes occurring since 1997. Courts at all levels sentenced 22,058 offenders for drug-related offences involving 288 death penalty, 255 sentences of life imprisonment, 2,292 of between 10 and 20 years in prison and 19,223 of less than 10 years or other kinds of punishment.[27] Although Vietnam succeeded in eradicating opium poppy cultivation, from an estimated 18,000 hectares in 1990 reduced to just 32,4 hectares in June 2004,[28] they remained an important Southeast Asian transit route for trafficking illicit drugs. Perhaps Marina Mahathir was correct with the specific statement, ‘traffickers continue to smuggle drugs across borders in a continuous game of cat-and-mouse with law enforcement’,[29] and they also ignore the strictest punishment under Vietnam’s regulations. Over the past three years, on average, more than 20,000 cases and 30,000 drug offenders have been detected and arrested annually, and substantial quantities of various types of drugs have been confiscated.[30] Notably, over 1,000 intricate drug locations have been eradicated, and numerous transnational drug trafficking routes have been dismantled, thereby preventing the smuggling of drugs from foreign countries into the domestic market. It is one of the main reasons there were different views when discussing the Draft of the 2015 CCV by the National Assembly at the 10th session (known as the Draft) to amend Article 194 of the 1999 CCV. While withdrawing capital punishment for illegal possession (Article 249) and appropriation (Article 252), Vietnam wants to retain it for illegal trading (Article 250) and transporting (Article 251). The Draft supports this argument due to one out of the three main reasons:

Geographically, our country is close to the “golden triangle”, a major illegal drug producer. To prevent international drug criminals from using our country as a transit point, it is necessary to apply preventive measures, including legal ones like the death penalty for illegal drug transportation.[31]

Particularly, the structure and modus operandis of those (transnational) drug trafficking groups have grown increasingly complicated in Vietnam that request to enhance professional enforcement activities. Examine the complexity of the trend and pattern of drug trading across the borderland between Vietnam and Laos in recent years, Luong (2020)[32] assesses that

The hot-spot drug trafficking routes across borderlands have continued to expand to different drug-related cases through cunning operations. Although the Government applied some strict measures with its absolute power for law enforcement agencies to counter-narcotics, the lucrative profits of illicit drugs have been “encouraging” traffickers to supply domestic markets.

2.2. Pressure the High Rate of Drug Use: Harder Punishment, Easier Management?

With the creation of compulsory centres through Resolution 06/CP in 1993, many people were forced to engage in centre-based compulsory treatment or CCT, even though most did not have a criminal conviction. Significant changes were made from 2000 to 2009 with some initial pilots of methadone maintenance therapy (MMT) for people who use drugs (PWUD) in Ho Chi Minh City and Hai Phong. Although these activities accordingly achieved positive outcomes regarding expenditure cost, physiologic, and management in the community, expanding this program at compulsory detention and prison for PWUD has not yet been prioritised. The high rate of PWUD at that time, with an increased average of 10,000 people annually, pushed more pressure on the CPV to adjust and implement drug control policies rather than investing only in ANPF to fight drug-related crimes. Since 2009, as the first country in Southeast Asia, Vietnam has decriminalised drug use, and no more imprisonment applies to PWUD (article 199) and abolishing capital punishment for organising use of illegal narcotics (article 197).[33] Alternatively, they have been under-sanctioned as an administrative measure and treated as a patient rather than a criminal. This effort reduced death row for organising the illegal use of narcotics and controlled the number of PWUD prisoners, respectively. However, it also increased pressure on CDC officers when covering many PWUDs annually.

Although Vietnam had already attempted to conduct several measures in the rehabilitation and education policies with PWUD, the sustainable outcomes of ensuring those drug users’ human rights were still questionable. Particularly, the Government passed and declared their expectations in the National Project to Renovating the Detoxicated Drugs Centres towards 2020 and orients in 2030 with promises to reduce from 123 CDCs to 71 centres in 2020 through changing these centre’s reductions into voluntary detoxification centres (VDC) and also establishing at least 30 private owners of VDC. Unfortunately, as of February 2023, there were still 97 CDCs and only 16 VDSs with licensed operations. The total number of PWUDs managed at these drug rehabilitation centres is 63,253 (January – December 2022), while the National Project promised to reduce around 20,000 people.[34] Furthermore, after fifteen years of decriminalising drug use (2009), Vietnam has not yet organised and assessed what they implemented in their relevant policies in the post-decriminalisation period. Indeed, they still pushed them into the CDCs, without or with limited MMT interventions, for up to two years with strict control, labour forces, and even physiology abuses. At the end of the 2010s, policymakers who support supply reduction operations and suspect harm reduction interventions continued questioning the effective finances for illegal drug users and registered drug abusers.

Regarding daily expenditure cost, if one PWUD needs around USD 1,000 annually plus around USD 85 for personal profiles with its necessary paperwork, the Government invested at least USD 248,043 million from 2009-2018.[35] Besides that, although the Government invested at least USD 44.6 million annually to run these CDCs, effective treatment is currently facing many problems and difficulties for many relapsed cases. To oppose these, since the early 2020s, in the latest amendment and supplement of law on drug prevention and control, the MPS’s representatives have proposed tougher restrictions and harder measures for PWUD by proposing to re-enact Article 199 (drug use) in the 1999 CCV, which decriminalised in 2009.

Currently, the high demand for drug users in Vietnam contributed to pull-and-push factors to make the situation of drug trafficking from neighbouring countries to Vietnam via land more difficult to control and manage. Although the CPV has passed several prohibition policies, including the death penalty for illegal drug trading and transporting combined with propaganda campaigns, the long-term effectiveness still raises questions when the rate of PWUD is still high, particularly with the amphetamine-type stimulant users in young groups. Alongside pushing PWUD into the CDC as the high priority of the demand reduction, it requires CPV and the Government to continue to support drug law enforcement agencies policing drug resources with the hardest strikes. As part of the supply reduction, ANPF has been encouraged to deploy all their professional operations to prevent and combat drug smuggling and trafficking. Consequently, it is also recorded as other reasons to require keeping the death penalty for drug trafficking activities, particularly for illegal trading and transporting. The Draft[36] noted that:

Despite some positive changes in drug prevention and control, the situation remains complex due to high relapse rates, ineffective detoxification, worrying levels of HIV infection among drug addicts, increasing use of synthetic drugs and crystal meth among teenagers, and sophisticated activities of organised, transnational crime. Abolishing the death penalty for illegal drug transportation could complicate the situation further, as life imprisonment may not be a sufficient deterrent

Many advocators believe that applying the death penalty to this group of criminals is entirely justified as it breaches the state’s monopoly on narcotics management and controls.[37] Recently, to control the rate of PWUD on a domestic scale (demand reduction), supply-driven reduction with policing measures continues to play as the pillar priority in the newest National Action Plan (2021-2025). Accordingly, CVP and the Government still requested to:

- Concentrate on preventing and effectively combat illegal transporting and trading from overseas to internal markets, dismantle entirely any transnational drug trafficking to investigate and prosecute those traffickers…

In other words, although the National Action Plan’s general goals expect to balance ‘overall supply, demand, and harm reduction solutions’ in theory, its specific actions need to be interpreted and implemented in practice. It could lead to blurred points and unclear studies for Vietnamese and non-Vietnamese who want to understand the nature of the counter-narcotics policies in Vietnam fully.

3.Discussions

Many changes have impacted the conditions and scope of applications of the death penalty in Vietnam after nearly 40 years since the first CCV in 1985. I am only a new scholar born in the Doi Moi era and had a timely chance to study and research in a Western country where I can open views with different approaches to review and examine what and how Vietnam changed and applied capital punishment. From a balanced perspective, I recognised that some of Vietnam’s policymakers have been urged to reform, reduce, and ultimately abolish this harsh punishment to make its legal system more humanitarian. Particularly when Vietnam implemented their first requirements of Judiciary Reform in the 2000s-2010s to look for optional reduction of the death penalty, including for drug-related offences. To date, there are 18 ‘particularly serious crimes’ for which capital punishment is imposed; only three of these crimes are drug-related crimes, in comparison to the seven drug-related crimes for which capital punishment was imposed in the 1985 CCV. This change reflects a trajectory leading from a strictly retentionist to a partly reductionist position towards the death penalty and needs further roadmap.[38] I also continue to agree with the straightaway comment of Professor Pip Nicholson, a leading expert in Vietnamese criminal justice reform, ‘Vietnam is reformist and reductionist through reduce the offences to which the death penalty applies given recent changes to their laws, its resumption of executions, to advance human rights – but it is premature to classify it as an abolitionist.’[39] Nicholson correctly sketched here the roadmap that will move Vietnam beyond reduction and towards the abolition of the death penalty for drug-related crimes.

Thus, I do not think some recent arguments by scholars and non-government organisations who rank Vietnam among the top non-humanitarian states with the highest applications of the death penalty reflect the positive objectives with specific efforts from Vietnamese policymakers. Vietnam has implemented many changes reducing capital punishment since the first CCV in 1985, with their reductions exceeding those of other current retentionists.[40] It may be that analysts are making arguments that lack information about legislative actions, practical applications, international reviews, and humanitarian policies in Vietnam regarding the use of the death penalty for drug offences. Again, with the country following up the punitive-based approach and leading under the Party, I assumed that drug laws in Vietnam would not transfer immediately to abolitionists without their specific conditions in the short-term of five years ahead.

In June 2019, a group of Vietnamese scholars worked with the Ministry of Justice and the Ho Chi Minh National Academy of Politics, with support from the EU Justice and Legal Empowerment Program in Vietnam, as well as UNDP and UNICEF, to organise a national workshop. Thirty interviews were conducted with government agencies, law enforcement officers, criminal justice officials, lawyers, and legal scholars. They also discussed the appropriate ways for Vietnam to enter the Second Optional Protocol of the ICCPR and abolish the death penalty. Accordingly, we should support Vietnam with a more detailed roadmap and accurate assessments to set up a comprehensive framework that can refer to Vietnam what and how to make suitable progress towards abolishing the death penalty in the future. It was also analysed and reflected in my latest five-year publications.[41]

Recently, reporting on the fourth cycle of the national report for the Human Rights Council Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) urged Vietnam to abolish capital punishment for all crimes, including drug offences.[42] As part of the continuous recommendations from three out of the fifteen countries for Vietnam’s report (Belgium, Leichesten, and the Netherlands),[43] they submitted their questions about what, when, and how Vietnam set up long-term approaches to reduce and abolish all death penalty offences after completing four stimulus UPR cycles. In any case, however, the roadmap leading to abolition must be synchronised with a one-term meeting of Vietnam’s National Assembly period in the new term (2021-2026). Again, it was not surprising when Vietnam continued to neglect supporting the 75th Session of the United Nations General Assembly (30 October 2020) and the 2nd Optional Protocol ICCPR to abolish the death penalty in the fourth cycle of UPR (7 May 2024).

To some extent, I propose seven specific recommendations for drawing the necessary roadmap to abolish drug offence groups, if applicable for Vietnam, which has been partly published in previous studies. By doing this, we can expect a review and re-balancing of international standards with national priorities, further facilitating the abolition or continued reduction of articles involving death sentences for drug-related offences before officially retaining or abolishing the death penalty.

Firstly, regarding scientific evidence, only one national survey has been conducted by the School of Law National University of Hanoi since the 2010s, alongside some internal research. Yet, this survey is a general assessment – ‘Survey on Impacts of Some Sentences in the Penal Code’, which did not design and focus on the death penalty to drug-related offences as an independent issue. Furthermore, trends and patterns of public opinion to objectively abolish or retain the death penalty for drug-related crimes have not yet been designed and analysed. Therefore, after 15 years, we call for a national survey focusing on drug-related offences as the first pilot before expanding to the rest of the 15 articles covering the death penalty.

If approved, secondly, this survey should be referred to and learnt in both design and conduct as professional and academic approaches in the Asia region and invited external experts to collaborate with the School of Law. As a typical example, I suggest kindly looking at the recent survey of public opinion on the death penalty in Singapore,[44] particularly in Chapter 3: Support for Death Penalty in Specific Offences and Chapter 5: Preferred Alternative Measures and Sentences, with a focus on drug-related crimes. To do it as objectively as possible, we can carefully examine the public opinion of each drug-related offence, both pros and cons. These findings about three drug-related offences should also be compared to the rest of the capital crimes in the current CCV (15 articles) to understand the general trend and pattern of capital punishment.

Thirdly, although the death penalty is still frequently applied, its effectiveness in deterring drug-related crimes is still questionable, as Nguyen’s proposed above statement since the 2010s. For the first national survey, we need to design three separate sections with each relevant article in the 2015 CCV (Article 248: illegal manufacturing; Article 250: illegal trading; and Article 252: illegal transporting) to collect and analyse data more objective and accurate what, how, and why Vietnam should or not maintain the capital punishment for those offences.

Fourthly, some specific circumstances and scenarios relating to those three drug-related offences should be included and explained to surveyors. For example, with illegally transporting drugs (Article 250), someone, including myself, proposed to withdraw the death penalty and transfer to life imprisonment as the highest punishment,[45] like illegal possession (Article 249) and illegal appropriation (Article 251), if drug mule belongs to some circumstances such as 1) the first time to commit a crime; 2) vulnerable groups, including homeless with poor economic, ethnic minorities, disabled persons or mental health; and 3) people who are seduced, forced or coerced to join trafficking networks.[46]

Fifthly, there is a need for an open-access workshop or seminar among experts in drug-related offences, including policymakers, law enforcement agencies, and scholars. Although few events have been organised recently by the United Nations and School of Law (with support from Melbourne Law School and the Anti-Death Penalty Asian Network), their themes and discussions were vague. They did not focus only on drug-related offences. Alternatively, such a workshop or conference will allow participants to discuss the use of the death penalty for drug offences in Vietnam and how Vietnam can reduce and abolish it in the future.

Sixthly, Vietnam need to clarify their legislative documents to regulate the death penalty as their state secret. Since the 2000s, Vietnam has classified the list of top-secret state secrets of the Court, including ‘files and documents related to the trial of cases of national security offences and reports, statistics of the death penalty and closed trials without public announcements’ (Decision No.01/2004/QD-TTg on 5 January 2004 of the Prime Minister). However, the latest regulation on the State Secret Listing in the Court (Decision No.970/QD-TTg on 7 July 2020 of the Prime Minister) divided it into two levels: extremely secret and secret. Accordingly, the death penalty belongs to a secretive level with five types, including ‘reports of the Courts relating to not yet executing the death penalty to serve the extensive investigation’s requests.’ In my view, this point still leads to some misunderstanding and confusion because leaders of the Ministry of Justice and the Ministry of Public Security have often informed the death penalty’s charges per year during their annual execution of criminal judgements at the National Assembly Meeting.

Seventhly, Vietnam should collect and analyse data in the five-year implementation of the latest criminal code, 2015 CCV (from it took effect on 1 January 2018 to 31 December 2023). It is a helpful database to reflect what and how effective the application of the death penalty is for three current drug offences (Article 248, 250, and 252). While Vietnam still classifies the database of cases involving the death sentence as ‘state secrets’, their authorities in the criminal justice system should conduct this first step for assessing internally. The data need to reflect and clarify the rate of applying capital punishment for each article. As Singapore’s recent survey found, this step can help Vietnam re-consider and re-scale the best pathway forward concerning these three articles.

Finally, as Table 1 shows, Vietnam should objectively assess and analyse three de facto abolitionists’ procedures and values, including two countries in the Golden Triangle region (Laos and Myanmar). Alongside Thailand, these countries have not executed in practice any drug-related offences for at least the past ten years. Continuing the form of a retentionist-and-reductionist state, Vietnam can withdraw for illegal transporting (Article 252) if some of the above conditions are met (see the fourth comment). Besides that, Vietnam can also keep capital punishment in law but without practising executions for illegal manufacturing (Article 248) and illegal trading (Article 250) to achieve physical and economic benefits. Doing so is likely to provide evidence for the argument that Vietnam should end killings for drug-related offences by taking the second step – namely, abolishing capital punishment.

Conclusion and Recommendations

The above brief of drug laws with its related capital punishment has reflected on Vietnam’s distinguishing perspectives in their make-policy decisions and legal frameworks. While the first version (1985 CCV) reflected the harshest punishment approaches with several offences in their criminal code, the newest one (2015 CCV) is showing to reduce the use of the death penalty. It shows us that the decision to maintain or abolish the death penalty in criminal law should be based on each nation’s unique characteristics, conditions, and crime-fighting requirements. Furthermore, capital punishment in Vietnam is not only to show a legal matter but also to cover political and social attitudes, particularly within the scope of CPV’s leadership, that led to limited reliable statistics regarding the practical application and executions. To some extent, thus, it is likely to be more curious for international human rights scholars and activists to conduct this topic in Vietnam. This study illustrated that one of the common trends in law enforcement agencies, policymakers, practitioners, and national assembly delegations is to favour retaining the harshest punishment for drug trafficking. With unclear evidence of crime deterrence theory through applying the death penalty, but they believe that applying the death penalty to this group of criminals is entirely justified because drugs are the root cause of various other crimes. Most consider that these drug-related offences contribute to the emergence of a new class of drug addicts in society, particularly among adolescents, causing significant harm and damage in terms of economic development, social stability, and traditional culture. These arguments have been presented and explained in the basic principles of Vietnam to affirm why Vietnam still maintains the death penalty for drug-related crimes. Twenty years ago, the CPV’s Resolution of the Politburo on Judicial Reform Strategy changed from ‘research to limit to apply the death penalty’ (Resolution No.08-NQ/TW in 2002) to ‘limit to apply the death penalty, only implementing to practically serious crimes’ (Resolution No.48 and No.49-NQ/TW in 2005). However, the latest version of the CPV in 2022 – Resolution No.27-NQ/TW on Continuing to Build and Improve the Vietnamese Socialist Rule-of-Law State in the New Period- had not yet mentioned the death penalty and its progress as the two previous resolutions. As above final/personal thoughts recommendations, rather than requesting/calling to abolish this punishment in Vietnam, we need further evidence to demonstrate what and how reducing/withdrawing the death penalty for some drug offences impacted social order and, in convert, whether keeping this punishment could(not) lead to crime prevention effectively before toward this abolishing expectation.

Bibliography

- Cao, N.A., Examining Drug Trafficking as a Human Security Threat in Vietnam. Journal of Security Studies, 2017. 19(Special issue).

- Chan, W.-C., et al., How Strong Is Pubic Support for the Death Penalty in Singapore? Asian Journal of Criminology, 2018. 13(2).

- Giang, O. Nhin Lai Mot Nam Thuc Hien Cai Nghien Ma Tuy Theo Luat Phong, Chong Ma Tuy 2021 [trans: Assessing the First Year to Rehabilitate Drugs from the 2021 Law on Drug Control]. News 2023 8 June [cited 2023 11 August]; Available from: <https://tiengchuong.chinhphu.vn/nhin-lai-mot-nam-thuc-hien-cai-nghien-ma-tuy-theo-luat-phong-chong-ma-tuy-2021-113230608092244765.htm>.

- Ginburgs, G., Soviet Sources on the Law of North Vietnam. Asian Survey, 1973. 13(7).

- Ginburgs, G., Soviet Sources on the Law of North Vietnam. Asian Survey, 1973. 13(10).

- Ho, T.N., Some Issues Related to Death Penalty Judiciary in Vietnam, in The XVII IADL Congress, IADL, Editor. 2009, International Association of Democratic Lawyers (IADL),: Hanoi, Vietnam.

- Jardine, M., et al., Harm reduction and law enforcement in Vietnam: influence on street policing. Harm Reduction Journal, 2012. 9(27).

- Johnson, D. and F. Zimring, The Next Frontier: National Development, Policy Change, and the Death Penalty in Asia. 2009, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Le, L.C., et al., Understanding Causes for Wrongful Convictions in Vietnam: A View from the Top and the Bottom of the Iceberg. Asian Journal of Criminology 2022. 17.

- Le, L.C., et al., Wrongful convictions in asian countries: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice, 2023.

- Leechaianan, Y. and D. Longmire, The Use of the Death Penalty for Drug Trafficking in the United States, Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia and Thailand: A Comparative Legal Analysis. Laws, 2013. 2(2).

- Luong, H.T., The Application of the Death Penalty for Drug-Related Crimes in Vietnam: Law, Policy, and Practice. Thailand Journal of Law and Policy, 2014. 17(1).

- Luong, H.T., Death Penalty to Drug-Related Crimes: A Vietnam Perspective, in Drug-related Offences, Criminal Justice Responses and the Use of the Death Penalty in South-East Asia, OHCHR, Editor. 2018, Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR): Bangkok, Thailand.

- Luong, H.T., Why Vietnam Continue to Maintain the Death Penalty with Drug-Related Crimes?, in 1st Asian Regional Meeting for Drug Policy, Centre of Criminology (Hong Kong University) and International Society for the Study of Drug Policy (ISSDP), Editors. 2019, Hong Kong University: Hong Kong.

- Luong, H.T., Drug Trafficking in the Mainland Southeast Asian Region: The Example of Vietnam’s Shared Borderland with Laos. Annals International of Criminology, 2020. 58(1).

- Luong, H.T., Why Vietnam Continues to Impose the Death Penalty for Drug Offences: A Narrative Commentary International Journal of Drug Policy, 2021. 88.

- Luong, H.T., et al., ‘We Realised We Needed a New Approach’: Government and Law Enforcement Perspectives on the Implementation and Future of the Drug Decriminalisation Policy in Vietnam. International Journal of Drug Policy, 2021. 87.

- Luong, H.T. and J. Ta, What Are the Specific Actions If Vietnam Still Retains the Death Penalty for Drug-Related Offences?, in Death Penalty in Asia: Law and Practice, S. Biddulph, et al., Editors. 2021, Social Science Publishing House: Hanoi, Vietnam.

- Luong, H.T., Capital Punishment in Vietnam, in The Elgar Companion to Capital Punishment and Society, B. Fleury-Steiner and A. Sarat, Editors. 2024, Edward Elgar: London.

- Mahathir, M., Foreword, in Drug Law Reform in East and Southeast Asia, F. Rahman and N. Crofts, Editors. 2013, Lexington Books: Plymouth, the U.K.

- Ministry of Public Security, Bao Cao Tong Ket Cong Tac Phong, Chong Toi Pham ve Ma Tuy o Vietnam nam 2020 [trans: Annual Report on Anti-Narcotics in Vietnam 2020]. 2021, Ministry of Public Security (MPS) Hanoi, Vietnam.

- Ministry of Public Security, Bao Cao Tong Ket Cong Tac Phong, Chong Toi Pham ve Ma Tuy o Vietnam nam 2021 [trans: Annual Report on Anti-Narcotics in Vietnam 2021]. 2022, Ministry of Public Security (MPS): Hanoi, Vietnam.

- Ministry of Public Security, Bao Cao Tong Ket Cong Tac Phong, Chong Toi Pham ve Ma Tuy o Vietnam nam 2022 [trans: Annual Report on Anti-Narcotics in Vietnam 2022]. 2023, Ministry of Public Security (MPS): Hanoi, Vietnam.

- Nagin, D., Criminal Deterrence Research at the Outset of the Twenty-First Century. Crime and Justice, 1998. 23(1).

- Nelder, V. and T.T.N. Pham, Application of Alternatives to Capital Punishment and the Right to Defence through Self-Representation in Criminal Proceedings: International Experiences and Recommendations for Vietnam. 2023, United Nation for Development Program (UNDP): Hanoi, Vietnam.

- Nguyen, G. Khong bo hinh phat tu hinh doi voi toi pham van chuyen trai phep chat ma tuy trong bo luat hinh su sua doi [trans: No Abolish the Death Penalty for Illegal Transporting Narcotics in Amendment and Supplement of Criminal Code]. 2015 [cited 2017 11 December]; Available from: <http://bocongan.gov.vn/vanban/Pages/van-ban-moi.aspx?ItemID=242>.

- Nguyen, T.P.H., Drug-Related Crimes Under Vietnamese Criminal Law: Sentencing and Clemency in Law and Practice, in Policy Paper, CILIS and ALC, Editors. 2015, the University of Melbourne: Melbourne, Australia.

- Nicholson, P. The Dealth Penalty in SE Asia: Is there a Trend Towards Abolition? Politics & Society 2015 2 October 2018 [cited 2019 11 December]; 4 March. Available from: <https://theconversation.com/the-death-penalty-in-se-asia-is-there-a-trend-towards-abolition-37214>.

- Nicholson, P., The Death Penalty and Its Reduction in Asia: An Overview, in Briefing Paper, Asian Law Centre, Editor. 2017, Melbourne Law School: Melbourne.

- OHCHR, Drug-Related Offences, Criminal Justice Responses and the Use of the Death Penalty in South-East Asia. 2018, Office of the United National High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) Regional Office for Southeast Asia: Bangkok, Thailand.

- Pascoe, D., Last Chance for Life: Clemency in Southeast Asian Death Penalty Cases. 2019, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Pham, V.B. Abolishing or Retention the Death Penalty for Some Crimes? Journal of Legal Studies, 2015.

- Rahman, f., Capital Punishment for Drug Offenses, in Drug Law Reform in East and Southeast Asia, F. Rahman and N. Crofts, Editors. 2013, Lexington Books: Plymouth, the U.K.

- Rapin, A.-J., Ethnic Minorities, Drug Use and Harm in the Highlands of Northern Vietnam: A Contextual Analysis of the Situation in Six Communes from Son La, Lai Chau, and Lao Cai. Project AD/VIE/01/B85 – Drug Abuse Prevention among Ethnic Minorities in Vietnam (2002-2004), ed. J. Eligh. 2003, Hanoi, Vietnam: Thegioi Publishing.

- Sidel, M., Law Reform in Vietnam: The Complex Transition from Socialism and Soviet Models in Legal Scholarship and Training. Pacific Basin Law Journal 1993. 11(2).

- Sidel, M., New Directions in the Study of Vietnamese Law. Michigan Journal of International Law, 1996. 17(3).

- Sidel, M., Law and Society in Vietnam: The Transition from Socialism in Comparative Perspective. Cambridge Studies in Law and Society, ed. C. Arup, et al. 2008, London, the U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

- Thu, H. Quy Hoach Mang Luoi Co So Cai Nghien Ma Tuy Den Nam 2020 Va Dinh Huong Den Nam 2030 [trans: Planning Project to Renovating the Detoxicated Drugs Centres Towards 2020 and Orients in 2030]. Van ban phap luat 2016 26 August [cited 2017 11 November]; Available from: <https://tiengchuong.chinhphu.vn/quy-hoach-mang-luoi-co-so-cai-nghien-ma-tuy-den-nam-2020-va-dinh-huong-den-nam-2030-11314395.htm>.

- Tran, T.H., Mot So Van De Ly Luan va Thuc Tien ve Hinh Phat Tu Hinh Trong Luat Hinh Su Viet Nam [trans: Basic Issues on Theory and Practice of the Death Penalty in Criminal Law of Vietnam], in School of Law. 2006, Hanoi National University]: Hanoi, Vietnam.

- Tran, H.N., Hinh Phat Tu Hinh Trong Luat Hinh Su Viet Nam [trans: The Capital Punishment in Criminal Law of Vietnam], in Luat Hinh su. 2003, Vietnam National University: Hanoi, Vietnam.

- Tran, K. and C.G. Vu, The Changing Nature of Death Penalty in Vietnam: A Historical and Legal Inquiry. Societies 2019. 9(3).

- Tran, V.H., Can mot lo trinh de tien toi xoa bo an tu hinh [trans: Need a Progress to Abolish the Death Penalty], in Tap chi Vietnam [Vietnam Journal], Thanh Phuong, Editor. 2014, Radio Fredoom International (RFI): Hanoi, Vietnam.

- Trinh, Q.T., Che dinh Hinh Phat Tu Hinh Trong Luat Hinh Su Viet Nam va Mot So Kien Nghi Hoan Thien [trans: The Death Penalty in Criminal Law of Vietnam - Proposed Issues to Improve]. Tap chi Luat hoc [trans: Law Journal], 2012. 28.

- United Nations International Convenant on Civil and Political Rights, General Comment No.36 on Article 6 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, on the Right to Life, in CCPR/C/GC/36, Human Rights Committee (HRC), Editor. 2019, United Nations: New York.

- UNODC, Vietnam Country Report. 2005, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC): Hanoi, Vietnam.

- UNODC, Synthetic Drugs in East and Southeast Asia: Latest Development and Challenges. 2021, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC): Bangkok, Thailand.

- UNODC, Synthetic Drugs in East and Southeast Asia: Latest Development and Challenges. 2022, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC): Bangkok, Thailand.

- UNODC, Synthetic Drugs in East and Southeast Asia: Latest Development and Challenges. 2023, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC): Bangkok, Thailand.

- Vu, C.G. and Q.D. Nguyen, Moving Away from the Death Penalty in Vietnam: Possibilities and Challenges, in Death Penalty in Asia: Law and Practice S. Biddulph, et al., Editors. 2021, Social Science Publishing House: Hanoi, Vietnam.

- Vuong, T., et al., The Political and Scientific Challenges in Evaluating Compulsory Drug Treatment Centers in Southeast Asia. Harm Reduction Journal, 2017. 14(2).

Footnotes

[1] Johnson, D., & Zimring, F. (2009). The Next Frontier: National Development, Policy Change, and the Death Penalty in Asia. Oxford: Oxford University Press; see also Rahman, f. (2013). Capital Punishment for Drug Offenses. In F. Rahman & N. Crofts (Eds.), Drug Law Reform in East and Southeast Asia (pp. 255-271). Plymouth, the U.K.: Lexington Books.

[2] Johnson, D., & Zimring, F. (2009). The Next Frontier: National Development, Policy Change, and the Death Penalty in Asia. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[3] Luong, H. T. (2021). Why Vietnam Continues to Impose the Death Penalty for Drug Offences: A Narrative Commentary International Journal of Drug Policy, 88, 1-9, p.2.

[4] Le, L. C., Hoang, H. Y., Bui, T. H., Nguyen, Q. D., Mai, T. S., & Luong, T. H. (2022). Understanding Causes for Wrongful Convictions in Vietnam: A View from the Top and the Bottom of the Iceberg. Asian Journal of Criminology 17, 55-73; see also Le, L. C., Hoang, H. Y., Bui, T. H., Nguyen, Q. D., Mai, T. S., & Luong, T. H. (2023). Wrongful convictions in Asian countries: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice, 1-18; Luong, T. H. (2018, 28 February). Death Penalty to Drug-Related Crimes: A Vietnam Perspective Drug-related Offences, Criminal Justice Responses and the Use of the Death Penalty in South-East Asia, Bangkok, Thailand; Luong, T. H. (2019, October). Why Vietnam Continue to Maintain the Death Penalty with Drug-Related Crimes? 1st Asian Regional Meeting for Drug Policy, Hong Kong; Luong, T. H. (2021). Why Vietnam Continues to Impose the Death Penalty for Drug Offences: A Narrative Commentary International Journal of Drug Policy, 88, 1-9; Luong, T. H., & Ta, J. (2021). What Are the Specific Actions If Vietnam Still Retains the Death Penalty for Drug-Related Offences? In S. Biddulph, S. Kowal, T. Q. A. Nguyen, C. G. Vu, K. T. La, & L. C. Le (Eds.), Death Penalty in Asia: Law and Practice (pp. 319-317). Social Science Publishing House.

[5] Luong, T. H. (2014). The Application of the Death Penalty for Drug-Related Crimes in Vietnam: Law, Policy, and Practice. Thailand Journal of Law and Policy, 17(1), 1-6; see also Tran, K., & Vu, C. G. (2019). The Changing Nature of Death Penalty in Vietnam: A Historical and Legal Inquiry. Societies 9(3), 1-28.

[6] Ho, T. N. (2009). Some Issues Related to Death Penalty Judiciary in Vietnam The XVII IADL Congress, Hanoi, Vietnam; see also Huyen, T. T. (2006). Mot So Van De Ly Luan va Thuc Tien ve Hinh Phat Tu Hinh Trong Luat Hinh Su Viet Nam Dai hoc Quoc gia Hanoi [trans: Huyen, Thi Tran 2006, “Basic Issues on Theory and Practice of the Death Penalty in Criminal Law of Vietnam” LLM Thesis, Hanoi National University]]. Hanoi, Vietnam; Tran, H. N. (2003). Hinh Phat Tu Hinh Trong Luat Hinh Su Viet Nam [trans: The Capital Punishment in Criminal Law of Vietnam]. (LLM Criminal Law). Hanoi National University], Hanoi, Vietnam.

[7] Nguyen, T. P. H. (2015) Drug-Related Crimes Under Vietnamese Criminal Law: Sentencing and Clemency in Law and Practice. In: Vol. 8. Policy Paper. Melbourne, Australia: the University of Melbourne; see also Trinh, Q. T. (2012). Che dinh Hinh Phat Tu Hinh Trong Luat Hinh Su Viet Nam va Mot So Kien Nghi Hoan Thien [trans: The Death Penalty in Criminal Law of Vietnam - Proposed Issues to Improve]. Law Journal, 28, 30-41.

[8] Pham, V. B. (2015). Abolishing or Retention the Death Penalty for Some Crimes? Journal of Legal Studies. Retrieved 11 December 2017, from: <http://lapphap.vn/Pages/tintuc/tinchitiet.aspx?tintucid=208505>; see also Tran, K., & Vu, C. G. (2019). The Changing Nature of Death Penalty in Vietnam: A Historical and Legal Inquiry. Societies 9(3), 1-28.

[9] The latest criminal code (2015) regulates this punishment may apply for three offences, including illegal manufacturing (article 248), illegal transporting (article 250), and illegal trading (article 251), if any trafficker has been demonstrated to commit these crimes at Clause 4 of each article, including:

- The offence involves a quantity of ≥ 05 kg of poppy resin, cannabis resin, or coca glue;

- The offence involves a quantity of ≥ 100 g of heroin, cocaine, methamphetamine, amphetamine, or MDMA;

- The offence involves a quantity of ≥ 75 kg of cannabis leaves, roots, branches, flowers, fruits or coca leaves;

- The offence involves a quantity of ≥ 600 kg of dried opium poppy fruits;

- The offence involves a quantity of ≥ 150 kg of fresh opium poppy fruits;

- The offence involves a quantity of ≥ 300 g of other solid narcotic substances;

- The offence involves a quantity of ≥ 750 ml of other liquid narcotic substances;

- The offence involves ≥ 02 narcotic substances. The total quantity is equivalent to the quantity of narcotic substances specified in points A through g of this Clause.

The English version is available at https://www.wipo.int/edocs/lexdocs/laws/en/vn/vn086en.pdf

[10] OHCHR. (2018). Drug-Related Offences, Criminal Justice Responses and the Use of the Death Penalty in South-East Asia. Retrieved from Bangkok, Thailand: <https://bangkok.ohchr.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Drug-Related-Offences-2018.pdf>.

[11] Nicholson, P. (2015, 2 October 2018). The Death Penalty in SE Asia: Is there a Trend Towards Abolition? Politics & Society. 4 March. Retrieved from: https://theconversation.com/the-death-penalty-in-se-asia-is-there-a-trend-towards-abolition-37214; see also Nicholson, P. (2017). The Death Penalty and Its Reduction in Asia: An Overview. Retrieved from Melbourne: <https://law.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/2675386/Nicholson-EN_final.pdf>; Pascoe, D. (2019). Last Chance for Life: Clemency in Southeast Asian Death Penalty Cases. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[12] General Comment No.36 on Article 6 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, on the Right to Life, (2019); see also OHCHR. (2018). Drug-Related Offences, Criminal Justice Responses and the Use of the Death Penalty in South-East Asia. Retrieved from Bangkok, Thailand: <https://bangkok.ohchr.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Drug-Related-Offences-2018.pdf>.

[13] Cheong, C., Ser, T., Lee, J., & Mathi, B. (2018). Public Opinion On The Death Penalty In Singapore: Survey Findings. Retrieved from National University of Singapore (NUS): <https://law.nus.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/002_2018_Chan-Wing-Cheong.pdf>.

[14] Luong, H. T. (2024). Capital Punishment in Vietnam. In B. Fleury-Steiner & A. Sarat (Eds.), The Elgar Companion to Capital Punishment and Society (pp. 287-292). London: Edward Elgar; see also Leechaianan, Y., & Longmire, D. (2013). The Use of the Death Penalty for Drug Trafficking in the United States, Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia and Thailand: A Comparative Legal Analysis. Laws, 2(2), 115-149; Luong, T. H., & Ta, J. (2021). What Are the Specific Actions If Vietnam Still Retains the Death Penalty for Drug-Related Offences? In S. Biddulph, S. Kowal, T. Q. A. Nguyen, C. G. Vu, K. T. La, & L. C. Le (Eds.), Death Penalty in Asia: Law and Practice (pp. 319-317). Social Science Publishing House.

[15] Sidel, M. (2008). Law and Society in Vietnam: The Transition from Socialism in Comparative Perspective. London, the U.K.: Cambridge University Press, p.45.

[16] Ibid, 2.

[17] Jardine, M., Crofts, N., Monaghan, G., & Morrow, M. (2012). Harm reduction and law enforcement in Vietnam: influence on street policing. Harm Reduction Journal, 9(27), 1-10; see also Cao, N. A. (2017). Examining Drug Trafficking as a Human Security Threat in Vietnam. Journal of Security Studies, 19 (Special issue), 69-90; Vuong, T., Nguyen, N., Le, G., Shanahan, M., Ali, R., & Ritter, A. (2017). The Political and Scientific Challenges in Evaluating Compulsory Drug Treatment Centers in Southeast Asia. Harm Reduction Journal, 14(2), 1-14.

[18] Nelder, V., & Pham, T. T. N. (2023). Application of Alternatives to Capital Punishment and the Right to Defence through Self-Representation in Criminal Proceedings: International Experiences and Recommendations for Vietnam. Retrieved from Hanoi, Vietnam: https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/2023-02/ENG_FINAL%20Alternatives%20to%20DP_%207Feb2023%281%29.pdf, p.49.

[19] Ginburgs, G. (1973). Soviet Sources on the Law of North Vietnam. Asian Survey, 13(10), 980-988; see also Ginburgs, G. (1973). Soviet Sources on the Law of North Vietnam. Asian Survey, 13(7), 659-676; Nagin, D. (1998). Criminal Deterrence Research at the Outset of the Twenty-First Century. Crime and Justice, 23(1), 1-42; Sidel, M. (1993). Law Reform in Vietnam: The Complex Transition from Socialism and Soviet Models in Legal Scholarship and Training. Pacific Basin Law Journal 11(2), 221-259; Sidel, M. (1996). New Directions in the Study of Vietnamese Law. Michigan Journal of International Law, 17(3), 705-719.

[20] UNODC. (2021). Synthetic Drugs in East and Southeast Asia: Latest Development and Challenges. Retrieved from Bangkok, Thailand: <https://www.unodc.org/documents/southeastasiaandpacific/Publications/2021/Synthetic_Drugs_in_East_and_Southeast_Asia_2021.pdf>; see also UNODC. (2022). Synthetic Drugs in East and Southeast Asia: Latest Development and Challenges. Retrieved from Bangkok, Thailand: <https://www.unodc.org/documents/scientific/Synthetic_Drugs_in_East_and_Southeast_Asia_2022_web.pdf>; UNODC. (2023). Synthetic Drugs in East and Southeast Asia: Latest Development and Challenges. Retrieved from Bangkok, Thailand: <https://www.unodc.org/roseap/uploads/documents/Publications/2023/Synthetic_Drugs_in_East_and_Southeast_Asia_2023.pdf>.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Luong, H. T. (2021). Why Vietnam Continues to Impose the Death Penalty for Drug Offences: A Narrative Commentary International Journal of Drug Policy, 88, 1-9, p.4.

[23] Notably, the current criminal code (2015) reduced death penalties to only three of these crimes are drug-related crimes, in comparison to the seven drug-related crimes in the first version (1985).

[24] Ibid, 5.

[25] UNODC. (2005). Vietnam Country Report. Retrieved from Hanoi, Vietnam: <http://www.unodc.org/pdf/vietnam/country_profile_vietnam.pdf>.

[26] Trinh, Q. T. (2012). Che dinh Hinh Phat Tu Hinh Trong Luat Hinh Su Viet Nam va Mot So Kien Nghi Hoan Thien [trans: The Death Penalty in Criminal Law of Vietnam - Proposed Issues to Improve]. Tap chi Luat hoc [trans: Law Journal], 28, 30-41.

[27] Rapin, A.-J. (2003). Ethnic Minorities, Drug Use and Harm in the Highlands of Northern Vietnam: A Contextual Analysis of the Situation in Six Communes from Son La, Lai Chau, and Lao Cai. Hanoi, Vietnam: Thegioi Publishing.

[28] UNODC. (2005). Vietnam Country Report. Retrieved from Hanoi, Vietnam: <http://www.unodc.org/pdf/vietnam/country_profile_vietnam.pdf>.

[29] Mahathir, M. (2013). Foreword. In F. Rahman & N. Crofts (Eds.), Drug Law Reform in East and Southeast Asia (pp. vii-viii). Plymouth, the U.K.: Lexington Books, p.vii.

[30] Ministry of Public Security. (2021). Bao Cao Tong Ket Cong Tac Phong, Chong Toi Pham ve Ma Tuy o Vietnam nam 2020 [trans: Annual Report on Anti-Narcotics in Vietnam 2020]; see also Ministry of Public Security. (2022). Bao Cao Tong Ket Cong Tac Phong, Chong Toi Pham ve Ma Tuy o Vietnam nam 2021 [trans: Annual Report on Anti-Narcotics in Vietnam 2021]; Ministry of Public Security. (2023). Bao Cao Tong Ket Cong Tac Phong, Chong Toi Pham ve Ma Tuy o Vietnam nam 2022 [trans: Annual Report on Anti-Narcotics in Vietnam 2022].

[31] Ministry of Public Security (nd). See more detail (Vietnamese) at <https://bocongan.gov.vn/van-ban/van-ban-moi/khong-bo-hinh-phat-tu-hinh-doi-voi-toi-van-chuyen-trai-phep-chat-ma-tuy-trong-bo-luat-hinh-su-sua-doi-242.html>.

[32] Luong, H. T. (2020). Drug Trafficking in the Mainland Southeast Asian Region: The Example of Vietnam’s Shared Borderland with Laos. Annals International of Criminology, 58(1), 130-151, p.136.

[33] The death penalty has now been abolished and changed to life imprisonment for organising the illegal use of narcotics in the 2015 criminal code (section 4, article 255); if committing a crime in one of the following cases, they include

- Causing harm to the health of 02 or more people with a bodily injury rate of 61% or more for each person.

- Killing 02 or more people.

[34] Giang, O. (2023, 8 June). Nhin Lai Mot Nam Thuc Hien Cai Nghien Ma Tuy Theo Luat Phong, Chong Ma Tuy 2021 [trans: Assessing the First Year to Rehabilitate Drugs from the 2021 Law on Drug Control]. Tieng Chuong (The Bell). Retrieved 11 August from: <https://tiengchuong.chinhphu.vn/nhin-lai-mot-nam-thuc-hien-cai-nghien-ma-tuy-theo-luat-phong-chong-ma-tuy-2021-113230608092244765.htm>.

[35] This number belongs to my consultancy report with Harm Reduction International about Drug Law Enforcement Expenditures in Vietnam in 2021. Accordingly, A standard spreadsheet template, developed and released in July 2020 by HRI, was used for reporting annual indicators of law enforcement and expenditure figures in activities about policing, interdiction, judicial process, penitentiary institutions, and compulsory drug treatment over the 2015—2020 period. It is part of my consultancy with Harm Reduction International (HRI). Unit costs and expenditures were collected in Viet Nam Dong (VND) and converted to USD using the annual exchange rates to avoid confusing decimal statistics.

[36] Ministry of Public Security (n.d). See more detail (Vietnamese) at https://bocongan.gov.vn/van-ban/van-ban-moi/khong-bo-hinh-phat-tu-hinh-doi-voi-toi-van-chuyen-trai-phep-chat-ma-tuy-trong-bo-luat-hinh-su-sua-doi-242.html

[37] Nguyen, G. (2015). Khong bo hinh phat tu hinh doi voi toi pham van chuyen trai phep chat ma tuy trong bo luat hinh su sua doi [trans: No Abolish the Death Penalty for Illegal Transporting Narcotics in Amendment and Supplement of Criminal Code]. Retrieved from http://bocongan.gov.vn/vanban/Pages/van-ban-moi.aspx?ItemID=242; see also Pham, V. B. (2015). Abolishing or Retention the Death Penalty for Some Crimes? Journal of Legal Studies. Retrieved 11 December 2017, from: <http://lapphap.vn/Pages/tintuc/tinchitiet.aspx?tintucid=208505>.

[38] Tran, V. H. (2014, 1 April). Can mot lo trinh de tien toi xoa bo an tu hinh [trans: Need a Progress to Abolish the Death Penalty] [Interview]. Radio Fredoom International (RFI) <http://www.rfi.fr/vi/viet-nam/20140407-can-mot-lo-trinh-de-tien-toi-xoa-bo-an-tu-hinh>.

[39] Nicholson, P. (2017). The Death Penalty and Its Reduction in Asia: An Overview. Retrieved from Melbourne: <https://law.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/2675386/Nicholson-EN_final.pdf>; see also Nicholson, P. (2015, 2 October 2018). The Death Penalty in SE Asia: Is There a Trend Towards Abolition? The Conversation. Retrieved 11 December from: <https://theconversation.com/the-death-penalty-in-se-asia-is-there-a-trend-towards-abolition-37214>.

[40] Nicholson, P. (2017). The Death Penalty and Its Reduction in Asia: An Overview. Retrieved from Melbourne: <https://law.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/2675386/Nicholson-EN_final.pdf>

[41] Luong, T. H. (2014). The Application of the Death Penalty for Drug-Related Crimes in Vietnam: Law, Policy, and Practice. Thailand Journal of Law and Policy, 17(1), 1-6; see also Luong, T. H. (2018, 28 February). Death Penalty to Drug-Related Crimes: A Vietnam Perspective Drug-related Offences, Criminal Justice Responses and the Use of the Death Penalty in South-East Asia, Bangkok, Thailand; Luong, T. H. (2019, October). Why Vietnam Continue to Maintain the Death Penalty with Drug-Related Crimes? 1st Asian Regional Meeting for Drug Policy, Hong Kong; Luong, T. H. (2020). Drug Trafficking in the Mainland Southeast Asian Region: The Example of Vietnam’s Shared Borderland with Laos. Annals International of Criminology, 58(1), 130-151; Luong, T. H. (2021). Why Vietnam Continues to Impose the Death Penalty for Drug Offences: A Narrative Commentary International Journal of Drug Policy, 88, 1-9; Luong, T. H., & Ta, J. (2021). What Are the Specific Actions If Vietnam Still Retains the Death Penalty for Drug-Related Offences? In S. Biddulph, S. Kowal, T. Q. A. Nguyen, C. G. Vu, K. T. La, & L. C. Le (Eds.), Death Penalty in Asia: Law and Practice (pp. 319-317). Social Science Publishing House; Luong, H. T. (2024). Capital Punishment in Vietnam. In B. Fleury-Steiner & A. Sarat (Eds.), The Elgar Companion to Capital Punishment and Society (pp. 287-292). London: Edward Elgar.

[42] See more details at https://documents.un.org/doc/undoc/gen/g24/024/70/pdf/g2402470.pdf?token=vBtuBERKPRy2hJK16l&fe=true

[43] See more details at https://uprmeetings.ohchr.org/Sessions/46/VietNam/Pages/default.aspx

[44] Cheong, C., Ser, T., Lee, J., & Mathi, B. (2018). Public Opinion On The Death Penalty In Singapore: Survey Findings. Retrieved from National University of Singapore (NUS): <https://law.nus.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/002_2018_Chan-Wing-Cheong.pdf>.

[45] See more details (Vietnamese) at http://lapphap.vn/Pages/tintuc/tinchitiet.aspx?tintucid=208505; https://quochoi.vn/hoatdongcuaquochoi/cackyhopquochoi/quochoikhoaXIII/Pages/danh-sach-ky-hop.aspx?ItemID=2708&CategoryId=0; https://quochoi.vn/uybantuphap/lapphap/Pages/home.aspx?ItemID=79

[46] Based on some informal conversations between the first author and anti-narcotics police officers in recent years, we can confirm that some of the officers are against imposing the death penalty for illegally transporting substances (article 250, the 2015 CCV), particularly with minority groups. Other officers confessed that implementing the death penalty, either by shooting or injecting prisoners with poison, could lead to adverse psychological effects for themselves, including chronic stress after participating in executions.