DIGITIZATION OF LEGAL AID SERVICES AND CRIMINAL JUSTICE TO THE DETAINEES IN INDIA

##plugins.themes.bootstrap3.article.main##

Abstract

This paper presents a micro-study of the scheme of legal aid services and the impact of its digitization on the administration of criminal justice in India based on the case study of the District Legal Services Authority (DLSA) of Surguja at Ambikapur in Chhattisgarh State (India). This DLSA has been found to suffer from proper empanelment, allotment and monitoring of criminal defense counsels to the detainees. The empanelled defense counsels have been reluctant to pursue the case of detainees at the bail and trial stages. Resultantly, fair criminal trial according to the due process of law has been compromised, the fundamental guarantee to free defense counsel has been threatened and public trust in the criminal justice system has been deteriorated. Heeding the reports and judicial directions, the Union Ministry of Law and Justice has introduced the digitization of legal aid services of all authorities and committees established under the NALSA Act, 1987. The website portals and mobile applications have been brought upon to facilitate the beneficiaries to apply for free legal aid and know about actions taken therein. Nonetheless, these endeavours have been found inadequate in the mission of administration of criminal justice particularly for the detainees.

Keywords: Digitization of Legal Aid services, empanelment, allotment and monitoring of criminal defense counsels, fair criminal trial, due process of law, detainees

Introduction

The criminal justice system of every democracy is composed of four typical government institutions such as police, prosecution, court and prison across the world. These institutions are established, maintained and administered by the State. The State decides the legal frameworks to dispense criminal justice within its territorial limits. Eventually, the State organization holds extraordinary positive and negative actions in the domain of criminal justice; positive actions of the State connote the exercise of reformative powers by the State to uphold the due procedure of law that protects the rights of accused persons in criminal matters, whereas, negative actions of the State refer exercise of coercive powers by the State in the criminal matters[1] that invades the liberty of the accused persons.[2] The accused person is the epicenter of the jigsaw puzzle from the beginning till the end in a criminal proceeding.[3] The due procedure of law emanates indispensable set of rights to an accused person that protects his liberty and human dignity before the criminal justice institutions across the world including India. An arrested person shall have right to be informed about the grounds of such arrest before his detention in custody and right to consult and defended by a legal practitioner of his choice,[4] and right to be produced before the Magistrate within 24 hours.[5] Deprival of any of these rights would turn the detention unlawful and ensue right to the accused person to be compensated from the State.[6] Right to be presumed innocent until guilt is proved,[7] trial by competent-impartial-open courts[8]and equal opportunity to be defended through a lawyer of his choice or State sponsored criminal defense lawyer[9] are another sets of rights of accused persons. Practically, as far as the exercise of right to defense of an accused person is concerned, he gets limited opportunity[10] as compared to mighty prosecuting wings of the State on the plot of the criminal proceedings.[11] The prosecuting State appoints and maintains ten-fold organized, experienced and trained paid prosecution lawyers to plead against the accused.[12] Only those accused persons may enjoy the universally articulated and municipally guaranteed rights relating to criminal justice who have sufficient means to hire a lawyer of their choice for defense. But an accused who has no sufficient means to hire experienced and trained attorneys to speak for their causes receive gross ignorance on the plot of criminal justice. It takes him in a dock position[13] where he is unaware of the complex procedure and legal language of the court[14] and to understand courtroom rituals and formalities.[15] This scenario becomes meagre when such an accused person is detained in prison and facing a criminal trial. To uphold fair criminal trial according to due process of law and commitments of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (hereafter ICCPR), criminal defense lawyers at the State’s cost are allotted to the detainees in India either by order of the court or at the request of detainees to the Legal Services Institutions (hereafter LSIs) established under the National Legal Services Authorities Act, 1987 (hereafter NALSA Act).

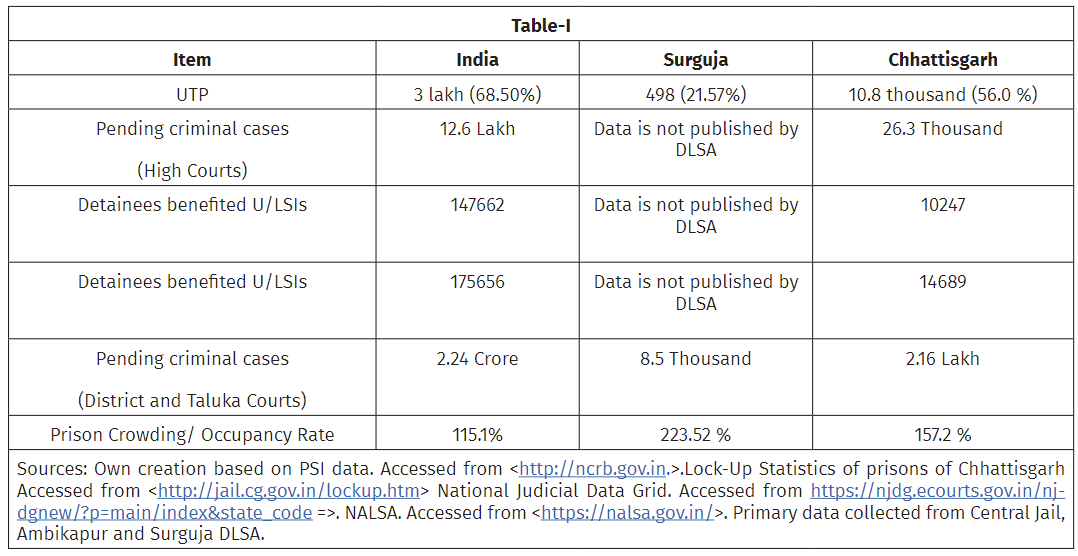

The District Legal Services Authorities (hereafter DLSAs) play a vital role in offering free legal services to the detainees because the pendency of criminal cases in District and Taluka criminal courts is significantly higher than in other courts in India. Table-I is produced to understand this scenario:

Separate data regarding a number of defense lawyers allotted to the detainees by order of the court or at application of detainees has not been displayed either by the National Legal Services Authority (hereafter NALSA), the State Legal Services Authorities (hereafter SLSA) or DLSAs. Further, the LSIs have not published the list of criminal panel lawyers and retainer lawyers. As such, it becomes difficult to present a categorical description of legal services provided to the detainees by the Surguja District Legal Services Authority to assess the convenient access of detainees to the DLSA to get defense lawyer of their choice in criminal trials.

State-sponsored legal aid to detainees has been recognized as an indispensable part of criminal justice administration across the world. It is a recognized human right as well as a fundamental right of detainees in democratic countries like India. State-sponsored legal aid to the detainees ensures the administration of fair criminal trial and due process of law. Notwithstanding the statutory scheme of legal aid services, Indian legal aid services have always been a serious topic of debate. A transparent and accountable mechanism for the appointment and allotment of lawyers is one of the issues, whereas monitoring such lawyers is another issue that has to be taken care of.

This paper aims to assess the functioning of Surguja District Legal Services Authority to empanel, allot and monitor legal aid lawyers to the detainees. This paper will also investigate the impact of the digitization of DLSA’s legal aid services on dispensing criminal justice to detainees. This paper has been divided into five sections. Section-1 is the introduction, section-2 is the origin and development of state-sponsored defense counsel, section-3 describes the empanelment and allotment of defense lawyers to the detainees by the DLSA, section-4 is the interview of officers of DLSA, Legal Aid Counsels (LACs) and beneficiaries of Surguja district (Chhattisgarh State of India) to assess the impact of digitization on the functioning of DLSA, and section-5 is the conclusion and suggestions.

- 1. STATE SPONSORED DEFENSE COUNSEL: ORIGIN AND DEVELOPMENT

The criminal trial procedure has traversed from three phases in juridical history. The criminal trial began with the accusatorial system in almost all countries, the then inquisitorial system appeared in the second phase, and nowadays, in the third phase, a mixed system is in operation.[16] The Anglo-American criminal trial procedure is accusatorial/ adversarial, and the inquisitorial criminal trial procedure is followed in the European continental countries except UK.[17] In the accusatorial/adversarial system the judge has no authority to decide its jurisdiction or obtain proofs on his initiatives instead he has to superintend the combats and rely inactively on the averments of the prosecution and defense to determine the criminal liability.[18] The prosecution and defense are private acts of the parties in this system. On the other side, the prosecution and detention are exclusively entrusted to the State agencies, and the State appointed judge actively participates in the inquisitorial system to discover the perpetrator bringing personal inquiries besides evidence produced by the parties.[19] The secret inquires are conducted, and torture is resorted upon the accused person to gather evidence against him. This system deprives the accused person of his right to defend himself. Nowadays, most criminal justice systems worldwide have adopted a mix of these two criminal procedures, borrowing the best elements from each. The accusation has been made over to the public prosecutors from the parties and judges. Judges are prohibited either to stay inactive or become proactive in the criminal trial procedures. They have been made duty bound to commence preliminary inquiry to assert the veracity of the case before arriving at the administrative-type decisions, and rationally apply their wisdom to the admissibility or inadmissibility of evidences produced before them. Initially, India inherited Anglo accusatorial/ adversarial criminal trial procedures, but later on, it switched to the mixed criminal trial procedure system.

Thus, progress in judicial civilization has created permanent prosecutorial organs of the State, such as public prosecutors, authorized them to prosecute the accused person in the criminal courts on behalf of the general welfare, and made victim parties secondary to prosecuting the accused person.[20] The accused has been brought into direct and unequal confrontation with the tenfold experienced State prosecutor. With the rise of criminal justice canons, the State sponsored defense lawyers for indigent detainees, and the State funded free defense lawyers for the detainees became integral parts of a fair trial and due process of law.

State-sponsored free legal aid to poor detainees is a universally recognized human right and municipally guaranteed fundamental and legal rights. Legal aid is an essential precondition for the exercise and enjoyment of a number of human rights, and it is an essential component of a fair and efficient criminal justice system founded on the rule of law to safeguard fairness and public trust in the administration of criminal justice.[21] Justice Black had underlined the necessity of legal aid in the Gideon v. Wainwright[22] that poor persons who cannot hire a lawyer and have been brought before the adversarial system of criminal justice cannot be assured equality before the law and a fair trial unless a defense counsel is provided to assist him. Free legal assistance has been recognized as an essential component of the right to a fair trial in several international and regional human rights treaties viz. under article 14 (3) (d) of the ICCPR, 1966; under article18 (3)(d) of the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families; under article 6 (3)(c) of the European Convention on Human Rights and under article 8(2)(e) of the American Convention on Human Rights.

At the early stage of criminal trial systems, accusation or defense was purely private action. With the transformation in the judicial system, the concept of ‘social accusation’ and ‘social defense’ grew up. The former Soviet Union, for example, acknowledged the scheme of ‘social accusation’ as well as ‘social defense’ of accused persons by their colleague coworkers depending upon their depreciation and appreciation of the accused’s moral character.[23] It began recognizing the public’s interest in criminal trials equally on accusation and defense levels. Statutorily, the State-sponsored legal aid scheme for poor litigants dates back to 1851 in France through enactment in the modern sense. The legal aid schemes for poor litigants grew around the world in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. The French enactment of 1801 enumerated the eligibility of beneficiaries under this programme. Corresponding to the French scheme, Italy (in 1865) and Germany (in 1877) also brought similar programmes allowing judges to appoint defense counsels to impoverished defendants.[24] Before the mid-nineteenth century, the legal aid to the poor litigants was purely charity. The French reform in 1972 substituted State-funded legal aid to the poor litigants for bare charity.[25] The UK enacted the Poor Prisoners’ Defence Act, 1903, empowering the courts to grant legal aid to indigent prisoners at committal proceedings. Further, the Poor Prisoners’ Defence Act of 1930 removed this requirement and reserved the grant of legal aid by the courts in the ‘interest of justice’ only. On the recommendation of the Rushcliffe Committee (1944), the Legal Aid and Advice Act of 1949, has added a ‘means test’ into the ‘interest of justice.’ On the recommendation of the Widgery Committee Report on legal aid in criminal proceedings (1966), the Legal Advice and Assistance Act of 1972 established a duty-solicitor scheme in the lower courts to provide legal aid to poor defendants at the courts’ discretion. The legal aid scheme was further strengthened in the UK by the Legal Aid Act of 1974 and the Legal Aid Act of 1982. The Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act, 2012 (LASPO) is the recent Act in the UK under which the legal aid scheme is governed.

The criminal justice administration in India is a State subject.[26] Nevertheless, article 39A of the Indian Constitution directs the State to make the policy by law to provide ‘free legal aid’ to needy persons at the expense of the State. In the M.H. Hoskot v. State of Maharashtra,[27] Justice Krishna Iyer observed that providing free legal aid is the State’s duty, not the Government’s charity. The State shall appoint competent counsel to the prisoner if he cannot engage a lawyer on reasonable grounds such as indigence or in communicado situation for the ends of justice. Such lawyer shall be paid such sum as the court may equitably fix. In the Hussainara Khatoon v. State of Bihar,[28] Chief Justice P.N.Bhagwati has ruled that the grounds and procedure to deprive a person of his life or liberty should be 'just, fair and reasonable’. Emphasizing upon article 39A, he further observed that the free legal services to the poor and the needy are an essential element of any ‘just, fair and reasonable’ procedure; it must be held implicit in the guarantee of Art. 21. In the Khatri v. State of Bihar,[29] Chief Justice P.N.Bhagwati has ruled that the right to free legal services is an essential ingredient of just, fair and reasonable procedure for a person accused of an offence, and it is implicit in the guarantee of Article 21. The State is under a constitutional mandate to provide a lawyer to an accused person if the circumstances of the case and the needs of justice so require, provided that the accused person does not object to appointment of such lawyer. The State cannot avoid its constitutional obligation to provide free legal services to a poor accused by pleading financial or administrative hardships. In the State of Maharashtra v. Manubhai Pragaji Vashi,[30] the Supreme Court has made it quite clear that it is now well-established rule of law that the failure to provide free legal aid to an accused at the cost of the State, unless refused by the accused, would vitiate the trial.

On the recommendations of Justice Iyer Committee on Legal Aid (1973) and Justice Bhagawati Committee for Implementing Legal Aid Schemes, the Parliament of India has enacted the National Legal Services Authorities Act of 1987. This Act has constituted permanent legal services institutions viz. the NALSA, the SLSA, the DLSA, the Taluka Legal Services Authority (TALSA), the Supreme Court Legal Services Committee (SCLSC) and the High Court Legal Services Committee (HCLSC). The procedure for the empanelment and allotment of legal aid counsels by these institutions has been described under the NALSA Act, 1987. Section 12 of this Act spells ‘means test’ for the beneficiaries, which under clause (g) includes detainees eligible for State-sponsored defense lawyers without any discrimination as to caste, sex, income or nature of the offence charged with.

- 2. EMPANELMENT AND ALLOTMENT OF DEFENSE COUNSEL BY THE DLSA

To empanel lawyers at the DLSA for a maximum period of three years,[31] the DLSA has to invite applications, accompanied with proof of the professional experience and preference of type of cases to be entrusted with,[32] from legal practitioners not having less than three years experience at the bar.[33] These applications are scrutinized and selection of the panel lawyers for the District and Taluka level is made by the Executive Chairman or Chairman of the DLSA in consultation with the District Attorney or Government Pleader and the Monitoring and Mentoring Committee at the DLSA.[34] While selecting panel lawyers, the Executive Chairman or Chairman of the DLSA has to consider competency, integrity, suitability and experience of lawyers[35] as well as representation of the Scheduled Castes, the Scheduled Tribes, women and differently-abled lawyers in the panel.[36] This list of panel lawyers is further approved by the Executive Chairman of the State Legal Services Authority.[37] The Executive Chairman or Chairman of the DLSA has to maintain separate panels for dealing with different types of cases like Civil, Criminal, Constitutional Law, Environmental Law, Labour Laws, Matrimonial disputes, Juvenile Justice, etc.[38] However, the Member-Secretary or Secretary of the DLSA may assign a case to a panel lawyer other than for which he has been empanelled.[39] For a period fixed by the Executive Chairman of the SLSA, and with his consultation, the chairman of DLSA may designate maximum ten Retainer Lawyers out of the panel lawyers at honorarium of minimum fifteen thousand rupees per month in addition to the honorarium or fee payable to him for the cases entrusted by the DLSA.[40] A panel or retainer lawyer may be withdrawn or may withdraw from a case by order of the Member-Secretary or Secretary of the DLSA.[41] Performance of panel lawyers has to be supervised by the Monitoring and Mentoring Committee at the DLSA[42] and they should be periodically trained as per modules prepared by the NALSA and the SLSA.[43]

As far as allotment of criminal defense lawyers is concerned, the DLSA does it either by order of the court or at the request of the accused person. The accused person gets defense lawyer from the DLSA in Sessions trial and Magistrate trial by order of the concerned court if he is not represented by a lawyer and the court is satisfied that he has no sufficient means to engage a lawyer.[44] On the other side, on its satisfaction that there is prima facie case to defend,[45] the DLSA allocates defense lawyer at the request of accused person who is a member of Schedule Caste of Schedule Tribe, a woman or child, disabled, in custody, or having annual income less than rupees nine thousand.[46] The Indian scheme of defense counsel to the detainees makes no distinction as to his caste, sex, age or annual income. He is entitled to a defence lawyer from the DLSA. If any detainee is applying to the DLSA for defense counsel, the DLSA has to provide him skilled defense counsel of his choice without inquiring his caste, sex or annual income. The detainee has the right to replace defense counsel from the DLSA if he is complaining that the previously allotted counsel is not satisfactorily defending his case.

- 3. IMPACT OF DIGITIZATION ON DLSA: INTERVIEW OF OFFICERS, LACs AND BENEFICIARIES OF SURGUJA (CHHATTISGARH STATE OF INDIA)

An intensive interview of the DLSA’s officers, Legal Aid Counsels (LACs), and beneficiaries of Surguja district has been conducted in this research work to assess impact of digitization on functioning of DLSA to dispense criminal justice to detainees. The size of sample chosen for this work is 67, which includes officers, LACs, and beneficiaries as target group. Separate questionnaires have been designed and served to these target groups.

- 3.1 INTERVIEW OF OFFICERS OF THE SURGUJA DLSA AT AMBIKAPUR

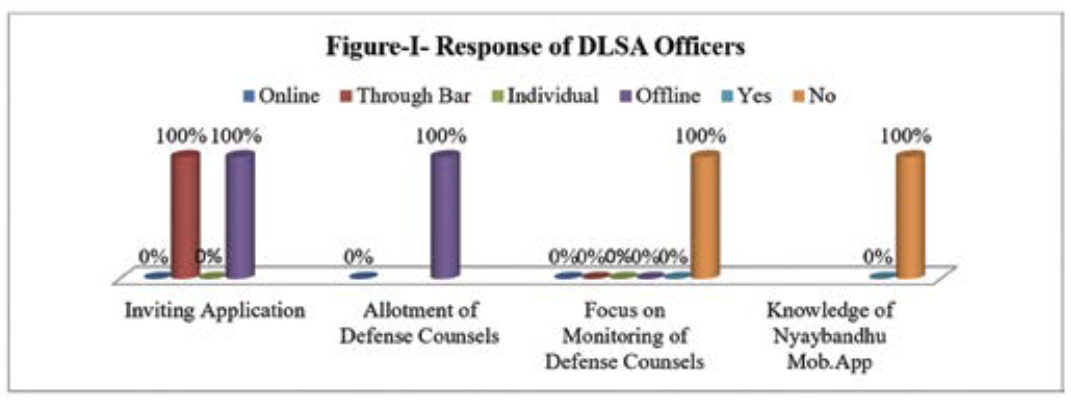

The chairperson and secretary of Surguja DLSA rightly refused to fill out the questionnaire; however, they participated in an oral interview. One clerk of Surguja DLSA has filled out the questionnaire. They were questioned about the procedure of appointment of LACs and Retainer Counsels (RCs), allotment of defense counsels to the detainees, monitoring of defense counsels and use of digital technologies to execute mandates of the NALSA Act, 1987. We get very shocking results. They said they invite applications for empanelment of LACs through the district bar only. They don’t invite applications from interested lawyers through advertisement publishing on their websites or newspapers. They consider applications forwarded by bar only, not individual applications. They don’t entertain interviews of applicants. They don’t look into lawyers’ commitment to social justice. Empanelment of lawyers is done very casually under the pressure of the district bar association. They give the least weight to new advocates with at least three years of bar experience. They appeared very reluctant about the appointment of RCs. They accepted that they don’t classify RCs and LACs according to expertise in civil, criminal and revenue matters and do allotment of defense counsels to the detainees without considering the choice of the detainees and expertise area of the counsels. They don’t accept online applications filed through the website or the Nyay Bandhu mobile App recently launched by the Ministry of Law and Justice of the Government of India. The DLSA website is non-functional for online applications, and DLSA officers are unaware of the Nyay Bandhu mobile App. They have been found careless about monitoring progress in cases assigned to defense counsels. One officer said, “once we have allotted defense counsel, we detach ourselves from further affairs. Now, it is a deal between the detainee and defense counsel. (Ek bar humane bachav adhivakta pradan kar diya, usake baad hum mamale men se bahar hut jaate hain. Ab yah kaidi aur bachav adhivakta ke beech kaa mamala ho jata hai.)”(See Figure-I)

- 3.2. INTERVIEW OF DEFENSE COUNSELS (LACS) APPOINTED BY THE SURGUJA DLSA TO THE DETAINEES

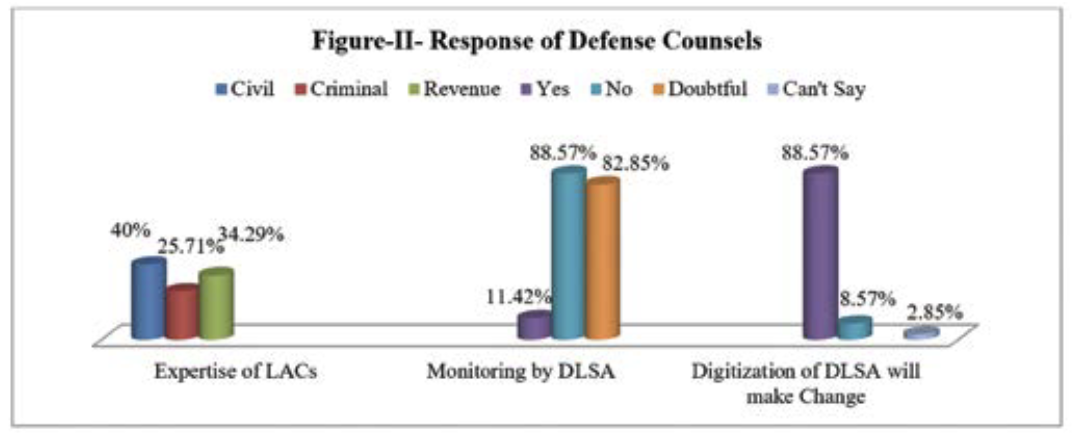

We conducted interviews with 35 LACs. They appeared very generous and comfortable to respond to our questionnaire. Out of 35 LACs, 27 counsels had applied through the bar, three counsels had applied directly to the DLSA, five counsels hadn’t applied but were selected for legal aid services because the bar had recommended names of 2 counsels, and three counsels were already working as LAC. The expertise of 26 defense counsels appointed through the DLSA was in civil or revenue matters only nine defense counsels were experts in criminal matters. 31 defense counsels had no information about the reporting of case status to the DLSA or monitoring of their works by the DLSA, only four defense counsels knew about it. They, too, don’t submit their reports to the DLSA. The allotment of defense counsels was seen as doubtful by 29 defense counsels. On the question of digitization of the functioning of DLSA for the appointment, allotment and monitoring of LACs, 31 defense counsels responded affirmatively. They thought that digitization would bring transparency in the appointment of LACs and the allotment of criminal cases to them. They were very anxious about the offline allotment of criminal cases to the LACs, which is being done without considering the expertise of LACs and their performance in previous cases. (See Figure-II)

- 3.3. INTERVIEW OF DETAINEES AT THE AMBIKAPUR CENTRAL JAIL

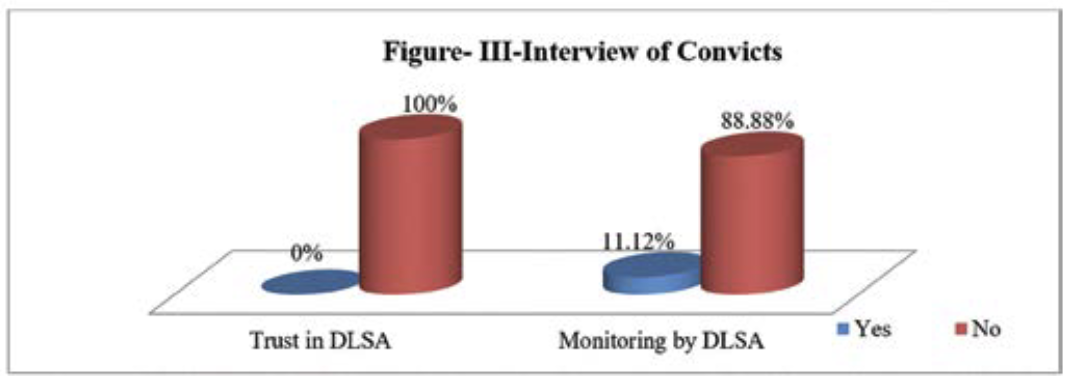

We interviewed 29 detainees charged with different offences; nine were convicts, and 20 were under-trial prisoners. None convict had heard from any of the Surguja DLSA officers about the scheme of free defense counsel; they knew it either through the jail officers or their next friends. Four convicts had no trust in the defense counsels of DLSA, therefore they didn’t apply for free defense counsel to the DLSA but rather engaged defense counsels at their own expense. The DLSA gave two convicts defense counsel on the court order, and three convicts were allotted defense counsels from the DLSA on their application. These five convicts reported that their defense counsels had never visited them in prison or their family members outside the prison, nor had they presented their case efficiently, due to which they had been held guilty. Two convicts said they had no information about complaints against their defense counsels otherwise, they would have made a complaint against them. Two convicts complained to the court about the insincerity of their defense counsels, but no action was taken. One convict said that his complaint was entertained by the DLSA, which re-allotted defense counsel to him. (See Figure- III)

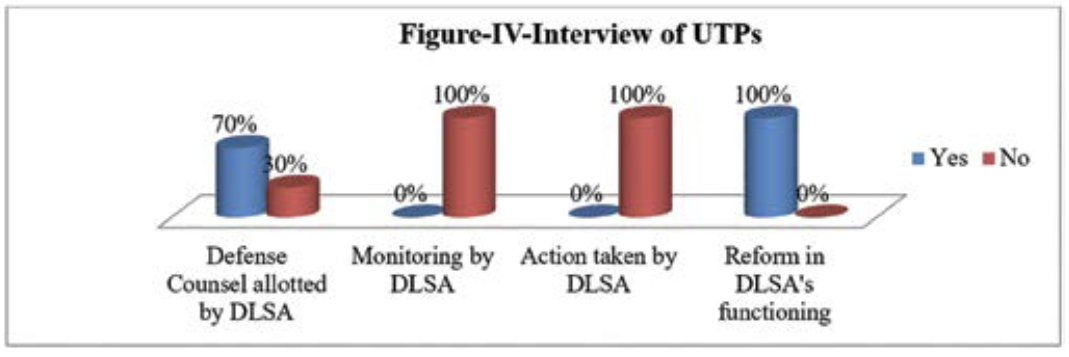

We interviewed 20 under-trial prisoners (UTPs). About free defense counsel, 14 UTPs came to know through jail officers, four UTPs came to know through jail officers and DLSA officers, and only two UTPs knew it solely from the DLSA officers. 14 UTPs were provided free defense counsels from the Surguja DLSA. 5 UTPs were happy with defense counsels, but 9 UTPs were unhappy with defense counsels, however only 3 UTPs had information that they could complain against insincere works of their defense counsels and they did compliant to the court, and Surguja DLSA but no action was taken due to which 2 UTPs engaged private defense counsels. 6 UTPs didn’t trust DLSA defense counsel; they engaged defense counsels at their expense. Nine UTPs were aggrieved that the defense counsels allotted to them by the DLSA had never communicated to them about the progress in their case; 3 UTPs were told about their case status by defense counsel before or after an appearance in the court, while only two UTPs were contacted in prison by defense counsels. All 14 UTPs were worried about the non-monitoring of the State-sponsored defense counsels by the Surguja DLSA. They wanted better mechanisms to ensure accountability in the functioning of Surguja DLSA than the present. (See Figure- IV)

- CONCLUSION AND SUGGESTIONS

The criminal courts at district level are pivotal in criminal justice administration. They are basically criminal courts of first instance for trial and determination of criminal liabilities of accused persons for any offence. The National Judicial Data Grid (NJDG) reports that about 34 million criminal cases are pending in District and Taluka Courts across India.[47] The Surguja district of Chhattisgarh contributes 11452 pending criminal cases.[48] This study reveals that around 70% of detainees are dependent upon the State-sponsored defense counsels provided by the DLSA.[49] Improper empanelment, allotment and monitoring of LACs by the DLSA have diluted confidence of detainees in the justice administration system. In spite of reiterated directions of the Supreme Court of India, the detainees are far behind in the free legal aid benefits, although there are well-crafted mechanisms under the NALSA Act of 1987.

It is noteworthy that most countries are now shifting their justice administration functions from manual to digital and receiving more public trust. Many countries have digitized their legal aid schemes, too. For example, Northern Ireland introduced a new digital Legal Aid Management System (LAMS) on 1 July 2019, accessible on various electronic devices. Now, calls for applications for legal aid, allotment of the LACs and payment of their fee are done online. It has speeded up processing times, reduced form-filling and use of paper, eliminated postage costs and, made provision of duplicate information and improved data accuracy.[50] The LAMS has brought transparency and accountability in the functioning of LSAs in the empanelment, allotment and monitoring of LACs. It has provided an open platform for legal aid seekers to get LACs of their choice and report their satisfaction or dissatisfaction to the LSAs.

Since 2007, India has introduced eCourts Integrated Mission Mode Project for the computerization of Districts and subordinate courts to improve access to justice using technology.[51] The NALSA, SLSA, SCLSC and HCLSC have initiated digitization of their functions. Various DLSAs in India’s districts have digitized their functions, but their digital services are practically in ideal condition. Recently, the Law Minister, Mr. Ravi Shankar Prasad, has promoted two legal aid mobile applications- Nyaya Bandhu and Nyaya Mitra to focus on access to legal aid services in the remotest areas in the country.[52] Astonishingly, the DLSA officers of the Ambikapur know less about these two mobile applications; LACs and detainees also have no information about it. However, most stakeholders in the legal aid scheme have shown their interest in digitizing the functioning of DLSA. They thought digitization would bring transparency in the empanelment of LACs and accountability in the allotment and monitoring of LACs.

Based on responses gathered from the stakeholders of the legal aid scheme, the following suggestions are proposed to make the functioning of DLSA more effective and carry out the mission of criminal justice:

- The empanelment, allotment and monitoring of LACs and RCs should be done by the DLSA through digitized mode only;

- The DLSA should display a list of criminal lawyers empanelled as LACs and RCs on its website;

- The DLSA should display report cards of LACs and RCs appointed for defense of detainees on its website;

- The DLSA should display action taken on complaints of detainees against defense LACs and RCs on its website;

The DLSA should endeavour to popularize the Nyaya Bandhu and Nyaya Mitra mobile applications for allotting and monitoring defense LACs and RCs.

Bibliography

Books

- Esmein, A. (2000). A history of continental criminal procedure: with special reference to France. pp. 67-78. Lawbook Exchange. ISBN: 978-1-58477-042-8.

- Jacobson, J., Hunter, G., & Kirby, A. (2015). Inside Crown Court: Personal experiences and questions of legitimacy (1st). Bristol University Press. pp. 111-138. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1t89fks

- Manning, D.S. (2009). Development of a Civil Legal Aid System: issues for Consideration. In Making legal aid a reality: A resource book for policy makers and civil society. Public Interest Law Institute. p. 61. ISBN 978-963-88337-0-9 .

- Reichel, P. L. (2018). Comparative criminal justice systems: A topical approach (7th ed). Pearson. ISBN: 978-0-13-455898-1.

- Young, R., & Wall, D. (Eds.). (1996). Access to criminal justice: Legal aid, lawyers & the defence of liberty. Blackstone Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-85431-502-1.

Article

- Johnston, K., Prentice, K., Whitehead, H., Taylor, L., Watts, R., & Tranah, T. (2016). Assessing effective participation in vulnerable juvenile defendants. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 27(6). pp. 802–814. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789949.2016.1208264

- Kirby, A. (2017). Effectively engaging victims, witnesses and defendants in the criminal courts: a question of “court culture”? Criminal Law Review pp. 949-968. ISSN 0011-135X. < https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/19508/3/19508.pdf> . [Last Access: 15 February 2024].

- Mulcahy, L. (2013). Putting the defendant in their place: Why do we still use the dock in criminal proceedings?, British Journal of Criminology, 63(6). pp. 1139–1156. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azt037

- Silva, A. (2000). The right to be informed of the grounds of arrest in criminal proceedings as guaranteed by the constitutions of the South‐Asian states and the European convention on human rights. The International Journal of Human Rights, 4(2), 44–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/13642980008406875

- Willey, P. (2014). Trials in absentia and the cuts to criminal legal aid: A deadly combination? The Journal of Criminal Law, 78(6), 486–510. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022018314557412

- Willey, P. (2014). Trials in absentia and the cuts to criminal legal aid: A deadly combination? The Journal of Criminal Law, 78(6). pp. 486–510. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022018314557412

Legal Acts

- The Code of Criminal Procedure (1973). Department of Justice. <https://lddashboard.legislative.gov.in/sites/default/files/A1974-02.pdf>. [Last Access: 15 February 2024].

- The Constitution of India (1950). Legislative Department. <https://cdnbbsr.s3waas.gov.in/s380537a945c7aaa788ccfcdf1b99b5d8f/uploads/2023/05/2023050195.pdf>. [Last Access: 15 February 2024].

- The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1966). UNGA. <https://treaties.un.org/doc/publication/unts/volume%20999/volume-999-i-14668-english.pdf>. [Last Access: 15 February 2024].

- The Legal Services Authorities Act (1987). Department of Justice. <https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/19023/1/legal_service_authorities_act%2C_1987.pdf>. [Last Access: 15 February 2024].

- The National Legal Services Authority (Free and Competent Legal Services) Regulations, 2010. National Legal Services Authority. <https://nalsa.gov.in/acts-rules/regulations/national-legal-services-authority-free-and-competent-legal-services-regulations-2010>. [Last Access: 15 February 2024].

- The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948). UNGA. <https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights>. [Last Access: 15 February 2024].

Newspaper

- Prasad, R.S. (3 June 2019). Law Ministry to focus on digitization of legal services. Business Standard. <https://www.business-standard.com/article/news-ians/law-ministry-to-focus-on-digitization-of-legal-services-prasad-119060300603_1.html>. [Last Access: 15 February 2024].

Official websites

- National Judicial Data Grid (2024). <https://njdg.ecourts.gov.in/njdgnew/?p=main/index&state_code=22~18&dist_code=4&est_code=undefined>

- Department of justice (2024). National Mission for Justice Delivery and Legal Reforms. Ministry of Law and Justice, Government of India. <https://doj.gov.in/vision-document/>

Gabriela, K. (2013). Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers. United Nations General Assembly. <https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/HRBodies/HRCouncil/RegularSession/Session23/A-HRC-23-43-Add3_en.pdf

Footnotes

[1] Manning, D.S. (2009). Development of a Civil Legal Aid System: issues for Consideration. In Making legal aid a reality: A resource book for policy makers and civil society. Public Interest Law Institute. p. 61. ISSN 978-963-88337-0-9.

[2] Young, R., & Wall, D. (Eds.). (1996). Access to criminal justice: Legal aid, lawyers & the defence of liberty. Blackstone Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-85431-502-1.

[3] Willey, P. (2014). Trials in absentia and the cuts to criminal legal aid: A deadly combination? The Journal of Criminal Law, 78(6), 486–510. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022018314557412

[4]The Constitution of India (1950). Article 22(1). Legislative Department. <https://cdnbbsr.s3waas.gov.in/s380537a945c7aaa788ccfcdf1b99b5d8f/uploads/2023/05/2023050195.pdf>. [Last Access: 15 February 2024]. International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1966). Article. 9(2). <https://treaties.un.org/doc/publication/unts/volume%20999/volume-999-i-14668-english.pdf>. [Last Access: 15 February 2024]. Silva, A. (2000). The right to be informed of the grounds of arrest in criminal proceedings as guaranteed by the constitutions of the South‐Asian states and the European Convention on Human Rights. The International Journal of Human Rights, 4(2), 44–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/13642980008406875

[5]The Constitution of India (1950). Article 22(2). Legislative Department. <https://cdnbbsr.s3waas.gov.in/s380537a945c7aaa788ccfcdf1b99b5d8f/uploads/2023/05/2023050195.pdf>. [Last Access: 15 February 2024]. International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1966). Article. 9(3). <https://treaties.un.org/doc/publication/unts/volume%20999/volume-999-i-14668-english.pdf>. [Last Access: 15 February 2024].

[6]International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1966). Article. 9(5). <https://treaties.un.org/doc/publication/unts/volume%20999/volume-999-i-14668-english.pdf>. [Last Access: 15 February 2024]. Rudul Shah v. State of Bihar (1983) 4 SCC 141 (India)

[7] The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948). Article 11(1). <https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights>. [Last Access: 15 February 2024]. International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1966). Article. 14(2). <https://treaties.un.org/doc/publication/unts/volume%20999/volume-999-i-14668-english.pdf>. [Last Access: 15 February 2024].

[8]The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948). Article 10. <https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights>. [Last Access: 15 February 2024]. International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1966). Article. 14(1). <https://treaties.un.org/doc/publication/unts/volume%20999/volume-999-i-14668-english.pdf>. [Last Access: 15 February 2024].

[9]The Constitution of India (1950). Articles 21, 22(1) and 39A. Legislative Department. <https://cdnbbsr.s3waas.gov.in/s380537a945c7aaa788ccfcdf1b99b5d8f/uploads/2023/05/2023050195.pdf>. [Last Access: 15 February 2024]. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948). Article 11(1). International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1966). Article. 14(3)(d). <https://treaties.un.org/doc/publication/unts/volume%20999/volume-999-i-14668-english.pdf>. [Last Access: 15 February 2024]. Khatri II v. State of Bihar (1981) 1 SCC 627.(Supreme Court of India)

[10] Johnston, K., Prentice, K., Whitehead, H., Taylor, L., Watts, R., & Tranah, T. (2016). Assessing effective participation in vulnerable juvenile defendants. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 27(6). pp. 802–814. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789949.2016.1208264

[11] Willey, P. (2014). Trials in absentia and the cuts to criminal legal aid: A deadly combination? The Journal of Criminal Law, 78(6). pp. 486–510. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022018314557412

[12] Ibid.

[13] Mulcahy, L. (2013). Putting the defendant in their place: Why do we still use the dock in criminal proceedings?, British Journal of Criminology, 63(6). pp. 1139–1156. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azt037

[14] Jacobson, J., Hunter, G., & Kirby, A. (2015). Inside Crown Court: Personal experiences and questions of legitimacy (1st ed.). Bristol University Press. pp. 111-138. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1t89fks

[15] Kirby, A. (2017). Effectively engaging victims, witnesses and defendants in the criminal courts: a question of “court culture”? Criminal Law Review 12. pp. 949-968. ISSN 0011-135X. < https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/19508/3/19508.pdf> . [Last Access: 15 February 2024].

[16] Esmein, A. (2000). A history of continental criminal procedure: with special reference to France. pp. 67-78. Lawbook Exchange. ISBN: 978-1-58477-042-8.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Id.

[19] Id.

[20] Id.

[21] Gabriela, K. (2013). Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers. United Nations General Assembly. <https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/HRBodies/HRCouncil/RegularSession/Session23/A-HRC-23-43-Add3_en.pdf>. [Last Access: 15 February 2024].

[22] Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963). <https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/372/335/#:~:text=Wainwright%2C%20372%20U.S.%20335%20(1963)&text=In%20a%20unanimous%20decision%2C%20the,appoint%20attorneys%20on%20their%20behalf.> [Last Access: 15 February 2024].

[23] Reichel, P. L. (2018). Comparative criminal justice systems: A topical approach (7th ed). Pearson. ISBN: 978-0-13-455898-1.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Id.

[26]The Constitution of India (1950). Seventh Schedule, entry 3, list-II Sate List. Legislative Department. <https://cdnbbsr.s3waas.gov.in/s380537a945c7aaa788ccfcdf1b99b5d8f/uploads/2023/05/2023050195.pdf>. [Last Access: 15 February 2024].

[27] (1978) 3 SCC 81.

[28] (1980) 1 SCC 98.The court referred to the decisions of Meneka Gandhi v. Union of India, [1978] 1 SCC 248; M.H. Hoskot v. State of Maharashtra, [1978] 3 SCC 544; Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 US 335; 9 L.ed. at 799; John Richard Argersinger v. Raymond Hamlin, 407 U.S. 25: 35 L. ed. 2d 530 at 535-36.

[29] AIR 1981 SC 262.

[30] AIR 1996 SC 1.

[31] The National Legal Services Authority (Free and Competent Legal Services) Regulations, 2010. Selection of legal practitioners as panel lawyers. Regulation 8 (13). National Legal Services Authority. <https://nalsa.gov.in/acts-rules/regulations/national-legal-services-authority-free-and-competent-legal-services-regulations-2010>. [Last Access: 15 February 2024].

[32] Ibid.Regulation 8 (1).

[33] Ibid.Regulation 8 (3).

[34] Ibid.Regulation 8 (2).

[35] Ibid.Regulation 8 (5).

[36] Ibid.Regulation 8 (6).

[37] Ibid.Regulation 8 (4).

[38] Ibid.Regulation 8 (7).

[39] Ibid.Regulation 8 (8).

[40] Ibid.Regulation 8 (9), (10), (11) and (12).

[41] Ibid.Regulation 8 (14) and (15).

[42] Ibid.Regulation 10.

[43] Ibid.Regulation 8 (18).

[44]The Code of Criminal Procedure (1973). Right of person against whom proceedings are instituted to be defended. Section 304. Department of Justice. <https://lddashboard.legislative.gov.in/sites/default/files/A1974-02.pdf>. [Last Access: 15 February 2024].

[45]The Legal Services Authorities Act (1987). Entitlement of legal services. Section 13. Department of Justice. <https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/19023/1/legal_service_authorities_act%2C_1987.pdf>. [Last Access: 15 February 2024].

[46]The Legal Services Authorities Act (1987). Criteria for giving legal services. Section 12. Department of Justice. <https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/19023/1/legal_service_authorities_act%2C_1987.pdf>. [Last Access: 15 February 2024].

[47]National Judicial Data Grid (2024). Pending Criminal Cases in India. <https://njdg.ecourts.gov.in/njdgnew/?p=main/index&state_code=>. [Last Access: 15 February 2024].

[48]National Judicial Data Grid (2024). Pending criminal cases in Surguja district of Chhattisgarh. <https://njdg.ecourts.gov.in/njdgnew/?p=main/index&state_code=22~18&dist_code=4&est_code=undefined>. [Last Access: 15 February 2024].

[49] This data is based upon response of the detainees of Ambikapur Central Jail, Surguja, Ambikapur.

[50]Department of Justice (2024). Digitisation of legal aid. Northern Ireland. <https://www.justice-ni.gov.uk/topics/legal-aid/digitisation-legal-aid>. [Last Access: 15 February 2024].

[51] Ministry of Law and Justice (2024). Digitization of Courts. <https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1896034>. [Last Access: 15 February 2024].

[52] Prasad, R.S. (3 June 2019). Law Ministry to focus on digitization of legal services. Business Standard. <https://www.business-standard.com/article/news-ians/law-ministry-to-focus-on-digitization-of-legal-services-prasad-119060300603_1.html>. [Last Access: 15 February 2024].