Maritime Piracy: A Maritime Crime with an International Dimension

##plugins.themes.bootstrap3.article.main##

Abstract

Maritime piracy is recognized as an international crime, constituting a phenomenon that has posed a continual threat to the security and stability of the international community, undermining both freedom of navigation and the safety of international trade.

Piracy increased markedly in the late twentieth century, becoming prominent in many regions around the globe. Because this crime does not target any one State in particular but endangers the security and integrity of the international community as a whole, pirates have been regarded as enemies of humanity, and their criminal acts are treated as directed against the international community.

The gravity of this offence has compelled the international community to adopt the necessary measures and procedures to prevent, combat, and mitigate it, given its impact on global security and safety. In particular, the repercussions of piracy in the Gulf of Aden and off the coast of Somalia generated a broad international consensus on the need to put an end to this problem and to pool collective efforts in addressing it. A variety of methods and strategies have since been employed by States and international organizations to confront maritime piracy.

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC), in numerous resolutions, has voiced profound concern over the rise in pirate attacks against vessels off Somalia’s shores, which have come to represent a genuine threat to ships’ safety and to navigation in that region. This concern has led to the provision of assistance to States that face challenges in dealing with this crime.

Keywords: Sea pirate, seas, international efforts, crime, maritime piracy.

Introduction

The worldwide threat of piracy has existed since ancient times, and it disrupts personal safety and international commerce, which leads to political and security problems for nations. The crime received international recognition during the late twentieth century as media and communication technologies advanced rapidly. Maritime peace and security face an escalating danger that threatens the fundamental bases that support worldwide trade operations across oceanic routes. The international community faces a threat from pirates who attack all ships because they do not discriminate against specific countries, which makes them hostes humani generis—enemies of all humanity—who harm the entire global population. Under international customary law, states can seize pirate vessels on the high seas or in maritime areas outside state jurisdiction, while various international treaties also criminalize this offense. The crime receives criminalization through international customary law because it allows states to seize pirate vessels operating beyond state jurisdictional boundaries on the high seas and in unclaimed maritime territories.

Accordingly, the central question arises: What is the specific nature of maritime piracy?

Methodology

The research employs a doctrinal legal analysis complemented by comparative and case-based methods. The doctrinal approach examines the evolution of the international legal framework on maritime piracy, from the 1958 Geneva Convention on the High Seas to the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and subsequent instruments.

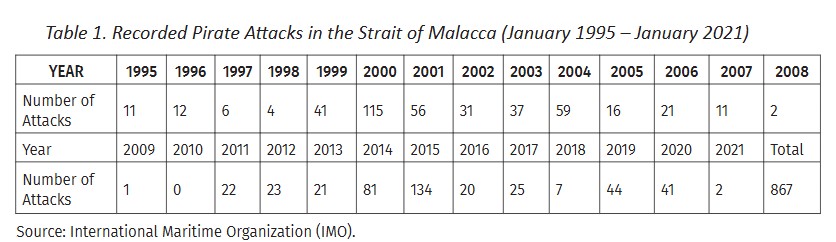

To reinforce the theoretical framework with empirical evidence, the study incorporates data and official reports from leading international institutions — including the International Maritime Organization (IMO, 2024), the International Maritime Bureau (IMB, n.d.), and the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC, 2020; 2021; 2023). These sources, such as the IMO’s Global Integrated Shipping Information System (GISIS) and UNODC’s Global Maritime Crime Programme and Pirates of the Niger Delta reports, provide verified statistical data and analytical insights on piracy trends, enforcement outcomes, and regional security initiatives.

In addition, the methodological framework is enriched by recent Scopus-indexed academic research applying quantitative and theoretical approaches to maritime piracy. Spatial and temporal models of piracy hotspots are considered (Tsioufis et al., 2024), along with theoretical interpretations of cyclical piracy dynamics (Frederick Boamah, 2023) and socio-economic perspectives highlighting the vulnerability of fishers and coastal communities (Amali Kartika Karawita, 2019).

This combined doctrinal–empirical–analytical design ensures both normative depth and data-based reliability. Accordingly, the study is structured around two main sections: the conceptual framework of maritime piracy (Section One) and the international efforts to combat this crime (Section Two).

To address this issue, we have decided to explore the conceptual framework of maritime piracy (Section One) and the international efforts to combat this crime (Section Two).

Section I: The Conceptual Framework of Maritime Piracy

Maritime piracy is considered one of the oldest issues that threatens the security and safety of maritime navigation, and it has undergone significant development. Therefore, a specific concept has been assigned to this crime (First Requirement). Additionally, this crime can only occur when its elements are present (Second Requirement).

A) The Concept of Maritime Piracy

Several definitions of maritime piracy have been proposed, including general definitions (Section One) and legal definitions (Section Two), along with an examination of certain regions where maritime piracy is most prevalent (Section Three).

1. The General Definition of Maritime Piracy

Maritime piracy is defined as a maritime crime that involves the robbery and plundering of ships, their crew, or the goods they carry. Many researchers have defined maritime piracy as the commission of one or more acts of violence against individuals and property in maritime facilities.

Maritime piracy is defined as theft committed at sea or sometimes on the shore by an agent not paid by any state or government. Some consider piracy to encompass all acts of violence committed against persons or property without legal justification on the high seas. Others define it as an armed assault carried out by a ship on the high seas, without authorization from any state, to obtain material gains through the seizure of ships, cargo, or persons.[1]

2. The Legal Definition of Maritime Piracy

The 1958 Geneva Convention on the High Seas was the first official framework for international law on maritime piracy. According to Article 15, the Convention defines piracy as having the following parts:

Any act of violence, illegal detention, or depredation perpetrated for personal gain by the crew or passengers of a private vessel or aircraft, aimed at:

- Another ship or plane on the open sea, or people or property on board such a ship or plane;

- Against another ship, plane, person, or thing in a place that is not under the control of any state;

- Any voluntary involvement in the operation of a vessel or aircraft with awareness of its participation in piracy;

- Any action that intentionally incites or helps someone commit the acts described in paragraphs (1) and (2).[2]

Similarly, Article 101 of the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) defines piracy as any of the following acts:

- Any unlawful act of violence, incarceration, or theft committed by passengers or crew members of a private aircraft or ship for their own benefit and directed:

- On the open sea, against another ship or plane, or against people or property on board;

- Against another ship, plane, person, or piece of property in a place that no state has control over;

- Any voluntary involvement in the operation of a ship or plane while knowing that it is engaged in piracy;

- Any act that incites the commission of one of the actions described in subparagraphs (a) or (b), or that intentionally facilitates their commission.[3]

It is clear from this article that the location of the offense is a defining element: piracy must occur either on the high seas or in areas beyond the jurisdiction of any state. This principle effectively places the duty of prosecution on all states, in accordance with the principle of universality. Conversely, anti-piracy measures within territorial waters fall under the exclusive jurisdiction of the coastal state; otherwise, such action would constitute unlawful interference with state sovereignty.[4]

It should also be noted that the definition of piracy in Article 101 of UNCLOS is restricted to unlawful acts committed in international waters. Acts of armed robbery at sea that occur within territorial waters are excluded, since international law does not permit the pursuit of pirates into the territorial jurisdiction of a sovereign state. In such cases, the coastal state itself bears sole responsibility for safeguarding its coasts and maritime domain. Moreover, the definition requires the involvement of at least two vessels: one being the victim, and the other serving as the platform from which the pirates launch their attack.[5]

While the 1982 UNCLOS did not substantially innovate upon the definition found in the 1958 Geneva Convention, a slight evolution is discernible. For the first time, it introduced the notion of “private ends” as the motivation behind acts of piracy (Article 101(a)). However, this terminology remains vague and open to multiple interpretations, as “private ends” may be construed flexibly depending on the interpreter’s perspective. It would arguably have been more precise for the drafters to specify that such ends are intended to achieve material gain or profit.[6]

The International Maritime Organization (IMO) oversaw the signing of the 1988 Convention for the Suppression of Unlawful Acts Against the Safety of Maritime Navigation (SUA Convention) in Rome. UNCLOS received partial criticism, which led to this convention being established as a response. According to Article 3(1) of the SUA Convention, the definition of unlawful acts extends beyond piracy and includes:

Any person who unlawfully and intentionally commits an offense through the following actions:

- Seizes or exercises control over a ship by force, threat of force, or intimidation;

- A person who performs violent acts against ship personnel will face prosecution when the act threatens ship navigation safety;

- Someone who damages or destroys a ship or its cargo in a way that could make it dangerous to navigate;

- A person who puts or causes to be put on a ship a device or substance that could destroy or damage the ship and make safe navigation impossible;

- A person who seriously damages maritime navigational facilities or seriously interferes with their operation in a way that endangers safe navigation;

- A person who provides false information that creates a danger to safe navigation;

- A person who harms or takes the life of someone while committing the mentioned offenses;

The SUA Convention provides the necessary legal framework to cover the gaps that UNCLOS leaves regarding territorial application, even though piracy remains unmentioned in its text. The SUA Convention surpasses UNCLOS by protecting unlawful acts which take place in territorial waters, together with archipelagic waters and internal waters as specified in Article 4.

This framework was further reinforced by the 2005 Protocol to the SUA Convention, which expanded the definition of unlawful acts by adding new provisions under Articles 3 bis, 3 ter, and 3 quater. These amendments incorporated additional offenses, thereby enhancing the comprehensiveness of the legal regime governing maritime security.

The 1988 Rome Convention, along with its 2005 Protocol, establishes a complete legal framework that protects maritime vessels from all potential forms of attack. The definition establishes boundaries that define both the goals and methods of these activities, thus making it applicable to a wider range of activities. The law protects all attacks against ships, which include those carried out by crew members and passengers against their own vessel. The 1958 Geneva Convention, together with the 1982 UNCLOS, failed to address this issue, which resulted in unclear interpretations of their rules.[7]

3. Manifestations of Maritime Piracy in Selected Regions: The Somali Coast, the Gulf of Guinea, and Southeast Asia as Case Studies

The Somali coastline stretches about 3,700 kilometers, and it overlooks vital international sea routes that connect the Indian Ocean and Arabian Sea to the Red Sea. The organized groups and gangs have proved their ability to control the area successfully. The groups maintain their own intelligence operations, which produce sophisticated maritime piracy activities through their combination of training and weaponry, and operational readiness. The group operates through shallow coastal waters where they use captured vessels as bases to conduct their operations while maintaining multiple armed support ships that carry weapons and fuel, and other necessary supplies. The target vessel detection leads them to send out fast boats, which carry armed personnel who use rifles and occasionally rocket-propelled grenades. The attackers use rope ladders to board their targets while they disguise their vessels as fishing boats to trick their victims and prevent early detection.

These groups use advanced communication equipment, which enables them to gather complete vessel intelligence before they start their attacks. Their operations are not random; rather, they carefully assess the type of ship, its cargo, and prevailing wind conditions. The experts who work in maritime fields say they spend no more than fifteen minutes to take control of the ship they want to capture. The main objective of these criminals involves demanding high ransom payments from victims who want to free their hijacked ships.

The maritime piracy activities that take place in Somali waters, as well as the Red Sea, create major security threats to nations because this waterway operates as a vital shipping route for international trade. The Red Sea creates an important shipping connection between seas and open waters while linking various continents together. The waterway serves as an essential shipping path for oil tankers, which move crude oil from the Arabian Gulf and Iran to international customers, and as a key trade route between Europe and Asia. The region has become dangerous for ships to sail because pirate vessels have increased their numbers and their aggressive behavior. Piracy operations have developed into an important business for various local communities, who now depend on them for their survival. The financial benefits from this activity exceed the dangers that exist when operating at sea. The modern form of piracy has developed into a profitable business enterprise.[8]

The spread of maritime piracy along the Somali coast can be attributed to two main categories of causes:

3.1 Internal causes

The problem of maritime piracy in Somalia emerged around 1991, coinciding with the outbreak of civil war. The central government lost control to insurgent groups, which caused wide instability to spread across the area. The region of Somaliland established independence through separatist forces, but international bodies refused to acknowledge this new political situation. The situation caused Somalia to transform into a nation that experienced deterioration and widespread insecurity, and lawlessness throughout its entire territory.[9]

The arrival of foreign ships into Somali waters became a major factor because local people viewed these vessels as foreign invaders who took advantage of their maritime territory. The Somali coast faced mounting pressure from foreign fleets that used modern trawling equipment to rapidly exhaust the abundant marine resources of the area. The Somali coastal area became a dumping ground for toxic waste because foreign ships started to dispose of their waste materials in this region. The local fishermen suffered a total loss of their daily fishing activities. The people of the region used basic tools to fight against foreign control, but their efforts led to harsh responses from the invaders. The fishermen reacted to foreign ships destroying their equipment by taking matters into their own hands because international organizations failed to protect them from illegal fishing activities.

3.2 External causes

There are several external factors that contributed, whether directly or indirectly, to the rise and spread of maritime piracy in Somalia. The most significant of these external causes was the American intervention in Somalia under the auspices of the United Nations in 1992. A massive force of 28,150 soldiers, in addition to 2,300 troops from 23 other countries, was deployed to disarm the militias. However, the outcome was the opposite of what many Somalis had hoped for. The confrontations resulted in casualties on both sides and caused extensive human and material losses. Moreover, these events left a profound psychological impact on Somalis, who perceived the intervention as an invasion that must be resisted. Consequently, many resorted to attacking ships on the high seas, which they regarded as a form of national defense.

It can therefore be said that acts of maritime piracy off the Somali coast have had a negative impact on the economies of the states bordering the region, on international trade in general, and on trade within the Arab and African regions in particular. These acts have increased the costs of international commerce due to the rise in commodity and product prices, driven by the additional expenses required for protecting large cargo vessels and by the higher insurance premiums imposed on ships and their cargoes by insurance companies. In addition, the states to which hijacked vessels belong, as well as the shipping companies that own them, are forced to bear the costs of paying ransoms demanded by pirates in exchange for the release of ships and their cargoes, especially oil tankers. Furthermore, victims themselves suffer substantial damages and losses.

To avoid the risk of exposure to maritime piracy in regions where such attacks are widespread, many ships and vessels have altered their routes, diverting instead to the Cape of Good Hope. This rerouting has resulted in increased costs, greater burdens, and longer travel times for voyages to reach their destinations.[10]

The Gulf of Guinea serves as a vital link between regional nations and international markets through its seaport trade operations for importing and exporting goods and services to major worldwide markets. The Gulf region holds substantial natural resources through its extensive marine life deposits and forest products, particularly fish and timber. The lack of strong national regulations for extraction and export makes the Gulf’s resources highly susceptible to various forms of exploitation.

The maritime insecurity in this region remains high because pirates continuously conduct attacks, which use innovative techniques to kidnap seafarers. The accumulation of maritime crimes has made it essential to implement a unified strategy for securing the region’s seas.

South China Sea piracy has existed since the 16th century through the 19th century. British naval forces, along with other state navies, effectively reduced pirate operations that took place on the South China Sea coastal areas. The end of colonial rule brought piracy back into existence. Most coastal nations inherited insufficient military forces, along with economic and political instability. Multiple scholars have demonstrated that the return of piracy emerges from widespread poverty, together with social inequality, alongside corrupt practices and nepotism, which postcolonial governments failed to address through proper governance and economic growth strategies.

Between 1983 and 2007, about 63% of all reported maritime piracy incidents took place in the Gulf of Guinea. The Gulf of Guinea remains under international scrutiny as a piracy-prone area, even though piracy rates decreased significantly in 2021 because recorded attacks happened every four to five days throughout 2016.[11]

It can therefore be argued that piracy has become a widespread phenomenon in the Gulf of Guinea since 2003–2004, making it undoubtedly the most dangerous region today. The Gulf, surrounded by mangrove forests and difficult-to-penetrate inland waters, is of strategic importance, as it holds the seventh-largest oil reserves in the world and the ninth-largest reserves of natural gas. It supplies the United States with 15% of its oil imports. While maritime traffic is not as dense as in the Strait of Malacca or the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, the Gulf is home to extensive industrial activity, particularly oil extraction, which requires reliable and predictable supply operations (supply vessels). The platforms are located about 20 nautical miles offshore, placing them either within territorial waters or in international waters. The Port Harcourt area, at the mouth of the Bonny River, is the most affected, as the city serves as a major hub for supplies, equipment, and the movement of personnel between offshore platforms and the mainland.[12]

According to the report prepared by the Secretariat of the United Nations Security Council on the main developments, trends, and considerations regarding piracy and armed robbery in the Gulf of Guinea, these activities have evolved in both nature and frequency.

In June 2021, the Global Maritime Crime Programme of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) traced the origins of piracy and armed robbery in the Gulf of Guinea to around 2005, when armed groups in Nigeria’s Niger Delta began attacking oil and gas infrastructure. At that time, incidents classified as “break-ins and thefts” accounted for 70% of reported cases, and more than 70% of all vessels attacked were support ships operating in the oil and gas sector.

Between 2005 and 2009, only about 15% of reported piracy incidents in the region fell under the category of “kidnapping for ransom”. However, the situation changed between 2010 and 2015, as certain pirate groups began to combine kidnapping of individuals with hijacking of ships, targeting primarily tankers carrying refined petroleum products—a pattern known as “oil piracy”.

Due to several factors, including the decline in global oil prices, incidents of tanker hijackings gradually decreased over time and had virtually disappeared by 2016.

From 2016 to 2021, pirate groups in the Gulf of Guinea shifted their operational patterns, focusing increasingly on kidnapping for ransom. According to a study conducted by the Global Maritime Crime Programme of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC)—which compiled data from multiple sources over the 2018–2020 period—this form of piracy peaked in 2020, when reports indicated that nearly 140 individuals were kidnapped at sea.

The pirate groups of previous years showed different behavior because they attacked all types of vessels without discrimination, while they extended their reach into distant offshore waters. The pirates demonstrated their ability to operate further from shore through multiple reported events, which took place at distances exceeding 200 nautical miles from the coast.

Positive developments became visible during the reporting period, while the previous events took place. The number of piracy and armed robbery incidents at sea, along with ransom kidnappings, decreased from 123 cases in 2020 to 45 cases in 2021. The Interregional Coordination Centre (ICC) for the Regional Strategy implementation of Maritime Safety and Security in Central and West Africa shows that maritime crimes stayed at a steady level during January to March 2021 because 20 piracy incidents took place during this period.

The number of maritime criminal activities has continued to decrease since April 2021 in the Gulf of Guinea, which includes both piracy and armed robbery offenses. For example, the Interregional Coordination Centre (ICC) recorded only nine incidents in the second quarter of 2021, and just eight incidents in the fourth quarter of the same year. The ICC recorded sixteen maritime crime cases during the first half of 2022, which showed a continuing downward trend from the previous year.

The Global Integrated Shipping Information System (GISIS) of the International Maritime Organization (IMO) supported this pattern through its records, which showed thirteen piracy and armed robbery incidents in the Gulf of Guinea from January to July 2022.[13]

The decrease in piracy activities throughout the Gulf of Guinea results from various connected elements. The Nigerian and Togo piracy convictions from July 2021 serve as a deterrent, and the Nigerian Navy has increased its naval patrols. The maritime security partners established better regional cooperation, which led to enhanced surveillance and response capabilities. The EU’s Coordinated Maritime Presences (CMP) initiative keeps Spanish, Italian, Portuguese, Danish, and French naval forces stationed in the area, which adds to the deterrent effect of outside naval deployments in the Gulf of Guinea. The navies of Russia, Brazil, Morocco United Kingdom United States, and India maintain regular patrols which have enhanced maritime security and reduced piracy incidents in the Gulf of Guinea. Pirate operations have spread across different global territories, with Southeast Asia becoming the primary area of operation. The ongoing effects of the worldwide financial collapse created conditions that led to increased criminal activities in this area. The attacks targeted the waters of the South China Sea and Malaysia, particularly in the zone stretching from northern Sumatra to the Philippine Islands. The South China Sea serves as a major shipping route that connects the Indian Ocean with the Pacific Ocean. The region contains strategic straits, including the Strait of Malacca and Singapore Strait, and also the Lombok and Sunda Straits of Indonesia. These maritime corridors experience about 8,000 vessels passing through them each year. However, the region’s geographic characteristics—its vast number of islands and complex terrain—have made it especially vulnerable to piracy. The natural environment provided ideal conditions for pirates to operate because they could attack quickly and then escape rapidly with their fast boats. International law defines maritime territories through coastal state territorial waters and archipelagic waters, contiguous zones, and related areas, which leave small portions of ocean classified as high seas. The Strait of Malacca operates as a vital international shipping corridor that runs through the territorial waters of three nations, including Malaysia, Singapore, and Indonesia. The geographic location enables pirate vessels to move between different states’ waters, which creates challenges for authorities to fight maritime piracy. The situation becomes difficult to enforce because the involved states have not established particular legal frameworks for enforcement. The states need to agree on joint actions and maintain open communication to fight against piracy in these areas.

Until 1980, piracy existed in East Asia but had not yet reached a large scale. The refugee crisis expanded because Vietnamese and Cambodian people fled their countries during multiple migration waves, which people called the “Boat People”. The 1958 Convention on the High Seas required Malaysia and Thailand to begin taking security measures in 1981 as both countries became signatories. The enforcement activities followed the rules stated in Articles 14 and 21 of the Convention. The implemented measures failed to control the increasing crime rate despite their implementation. The International Maritime Bureau (IMB) issued a warning to the global community about increasing maritime piracy incidents, which became more prevalent after 1992, especially in Southeast Asia. The financial crisis of 1997 in Asia made the situation worse than before. The economic crisis in Asia forced many Indonesians to relocate to Singapore because they needed improved financial prospects, so they moved to islands near Singapore, which included Riau Islands and Batam, and Bintan. The free-trade zone in Singapore experienced major population growth during this time, but it faced negative impacts from the regional economic slump. The maritime piracy incident index for the year 2000 showed a significant increase when compared to previous years. The Strait of Malacca experienced 75 pirate attacks along with 119 additional piracy events throughout Southeast Asia during that year. The alarming statistics forced coastal states to increase their maritime security measures while fighting piracy more aggressively. The MALSINDO Regional Agreement came into existence through this initiative when Malaysia joined Singapore and Indonesia to form a partnership in 2004. The agreement established joint naval patrol operations, which led to a significant decrease in piracy activities by 2009 around the Natuna and Anambas and Mangkai, and Tioman Islands.

The operational methods of pirates in Southeast Asia, which people call modus operandi, have undergone continuous development from a legal perspective. Pirate operations start on land before using “mother ships” to move from the territorial waters of states to reach open sea areas. Southeast Asian pirates have adopted Somali piracy methods to increase their operational activities, according to recent reports.[14]

4. Examples of Ships Subjected to Maritime Piracy

This section presents two illustrative cases of ships that were subjected to acts of maritime piracy: the Sirius Star and the Maersk Alabama.

4.1 The hijacking of the Sirius Star:

Maritime piracy off the coast of Somalia reached unprecedented levels in 2008, the year when the massive oil tanker Sirius Star was hijacked. That same year, pirates began targeting larger vessels carrying cargoes of far greater value than ever before.

The French luxury yacht Le Ponant, along with its thirty crew members, became a hostage to Somali pirates in April of that year. The military forces of France, who were stationed in Djibouti, moved to the incident location to free the captured crew members. The pirates received a monetary payment, which served as ransom to obtain their release.

The Ukrainian vessel M/V Faina became a victim of Somali pirates who called themselves the Central Regional Coastal Guards on September 25, 2008, during its journey to Mombasa port in Kenya. The ship transported military equipment which had a value of about thirty million dollars, including multiple T-72 tanks and RPG launchers, and anti-aircraft guns. The operation stood out because the pirates usually attacked civilian ships and oil tankers instead of military vessels. The vessel was released only after its owner paid a ransom exceeding 3.2 million U.S. dollars, following threats by the pirates to blow up the ship.

The Sirius Star incident occurred on November 17, 2008, when a group of pirates hijacked the supertanker, which was sailing under the Liberian flag and bound for the United States via the Cape of Good Hope. The hijacking took place approximately 450 nautical miles southeast of Mombasa, near the coast of Kenya.

The Sirius Star tanker operated with a crew of twenty-five people who came from multiple countries, which included Croatia and Britain and the Philippines and Poland, and Saudi Arabia. The tanker served as the second unit within a series of six identical vessels built by Vela International Marine Ltd., which functions as a maritime transport company under Saudi Aramco. The company operates a large fleet of vessels of different types, sizes, and functions, all constructed by Daewoo Shipbuilding & Marine Engineering (DSME), a South Korean shipbuilding corporation.

Vela International functions as a crude oil transportation company that links Ras Tanura Port in Saudi Arabia to European destinations and Gulf of Mexico ports through the Suez Canal and Cape of Good Hope routes. The Sirius Star stood as DSME’s 100th supertanker, which they built at their Okpo Shipyard located in South Korea.

4.2 The hijacking of the Maersk Alabama by Somali pirates

The worldwide public drew their attention to the Maersk Alabama hijacking by Somali pirates in April 2009 because it exposed dangerous maritime security weaknesses and revealed multiple economic and political consequences for the surrounding region. A group of pirates operating in Somali waters captured this vessel because they wanted to obtain ransom payments. The international media spotlighted this event because Richard Phillips became a hostage when the ship’s captain, which led to a situation that required the United States military to perform a direct rescue operation.

The Maersk Alabama operated as a cargo vessel in Somali waters, which served as a known hotspot for maritime piracy activities. The political instability in Somalia and the widespread poverty across the country have been among the principal causes behind the proliferation of piracy in the region. The current circumstances make vessels operating near Somali waters at high risk of being targeted by attacks.

The Maersk Alabama served as one of the targeted vessels which operated as a container ship built to handle massive amounts of goods through shipping containers. The ship played a vital role in worldwide trade because it could transport various types of cargo including industrial products and consumer goods. The Maersk Alabama followed specific shipping routes that traveled through important global trade routes that connected different international ports. The trade routes faced ongoing pirate threats because criminal organizations took advantage of Somalia’s economic difficulties. The event shows how vital maritime security functions to protect worldwide trade operations from increasing security threats.

The incident began in April 2009, when the Maersk Alabama was sailing from the Port of Oman to Mombasa, Kenya. The hijacking incident, which occurred in the Gulf of Aden, became a major international news story. The ship’s American crew became victims of the pirates as they captured the vessel during their assault.

Captain Richard Phillips of the Maersk Alabama received warnings about pirate attacks in Somali waters before he started his voyage. He chose to ignore the advice that was given to him. The next day, the crew detected a distant small boat that carried four armed pirates. The crew tried to defend their ship by firing flares and spraying water, but the pirates managed to board the vessel and take control. The attackers faced resistance from Captain Phillips and his crew members until they managed to capture some of them, who took hostages on the ship’s bridge.

The Maersk Alabama hijacking by Somali pirates became the most notorious maritime kidnapping event of the 21st century, which drew worldwide attention because of its intense hostage situation. The legal response to the incident involved rescue operations, judicial proceedings in the United States, and international cooperation in the broader fight against maritime piracy.

The United States government reacted immediately by deploying U.S. naval, air, and ground forces to conduct a rescue mission. Captain Phillips remained captive on a small lifeboat in open waters while the pirates tried to reach the Somali coast. The U.S. Navy forces executed a precise rescue mission on April 12, 2009, which led to the death of three Somali pirates who held the captain hostage and the capture of one pirate alive. The rescue operation brought Captain Phillips back to safety with physical health intact, but his mental state remained severely affected by the traumatic experience.

The surviving pirate, Abduwali Abdukhadir Muse, was apprehended by U.S. forces and brought to the United States to stand trial. He was one of the five pirates involved in the hijacking of the Maersk Alabama. Muse faced trial at a U.S. federal court in New York, where he admitted guilt to piracy and hostage-taking, and robbery charges during his 2010 plea. The federal court delivered a prison sentence to him in the United States in 2011.

The United States government showed its commitment to justice and maritime crime prevention through its naval rescue operation and pirate prosecution. The case shows how international piracy response requires multiple countries to work together because piracy activities span across different national territories and involve various international participants. The analysis requires examination of social and economic factors that sustain piracy activities across international waters.

The Maersk Alabama incident reaffirms the significance of applying international legal principles in combating transnational crimes such as maritime piracy. The prevention of crime requires both effective law enforcement and crime prevention systems to operate together. The United States executed all necessary legal steps through its rescue operation and offender prosecution to show its commitment toward an open and rigorous criminal justice system for handling these serious crimes. The case established a key legal precedent that became part of international law for fighting maritime piracy.

Muse stood with other pirates who faced death or capture during the Maersk Alabama rescue operation. Authorities transferred most of the arrested individuals to courts that held jurisdiction over their crimes because these offenses took place either inside their borders or involved their citizens. The world started paying attention to piracy when the Maersk Alabama got hijacked in 2009 because it showed how dangerous piracy had become in the Gulf of Aden and near Somalia. The hijacking demonstrates how piracy has transformed into a major problem that disrupts worldwide commercial shipping operations.

The international community responded to this threat by increasing its anti-piracy efforts through multiple international naval patrols. The European Union operates Operation Atalanta as its main security initiative to protect shipping operations in this particular area. The creation of an international task force that includes maritime nations like the United States and the United Kingdom represents a major development in this field. The joint initiative focuses on enhancing maritime security through efforts to decrease piracy attacks, which damage worldwide economic systems while protecting seafarers who operate in dangerous maritime zones.

Ship hijackings in international waters, such as the Maersk Alabama incident, create two major problems because they put human lives in danger and violate essential human rights to safety and secure employment. The protection of sailors’ rights and the international legal order requires essential measures to increase maritime surveillance and worldwide cooperation against piracy.

International trade route disruptions through criminal activities lead to major financial harm, which affects both state entities and business organizations, thus creating long-term economic damage. The world will experience major economic stability benefits through international collaboration to eliminate piracy, and when nations establish efficient preventive systems.

The Maersk Alabama hijacking by Somali pirates demonstrated why international and domestic legal systems must work together to fight cross-border offenses and protect human rights while combating piracy and hostage situations in international waters. The United States government deployed U.S. Navy special forces to conduct rescue operations because international law permits states to protect their citizens when they face threats from hostage-taking or piracy. The battle against transnational criminal activities depends on international legal frameworks, which define state powers to enforce laws beyond their national limits.

The United States used its domestic court system to handle the Abduwali Abdukhadir Muse trial, which took place within its borders for crimes committed outside its territory. The case demonstrates how international piracy requires worldwide cooperation because it occurs in international waters and affects various international criminal offenses that need a collective response. Operation Atalanta and the international working group established by the EU show how multinational collaboration becomes essential for addressing this threat. The solution to piracy requires maritime stakeholders to work together because piracy disrupts international trade routes.

Piracy continues to be a problem, which has led to debates about creating international courts or national courts that would handle cases of crimes committed in international waters to hold perpetrators accountable. The case shows how piracy crimes get handled through the combined use of international law and domestic criminal law and interstate cooperation. The system achieves victim justice through its dual role of defending global maritime security and protecting the interconnected world from rising security threats.[16]

B) The Elements of the Crime of Maritime Piracy

For the crime of maritime piracy to be established, all of its constituent elements must be present. These include the legal element (Section One), the material element (Section Two), the moral element (Section Three), and finally the international element (Section Four).

1. The Legal Element of the Crime of Maritime Piracy

The legal element of any crime refers to the existence of a legal provision that criminalizes the act and prescribes a penalty for it. Maritime piracy is criminalized under public international law, both through its established principles and through international conventions, given that such acts involve assaults on persons and property.[17]

Accordingly, the legal element of the crime of maritime piracy refers to the commission of acts of plunder by a ship’s crew or by passengers on board. It makes no difference whether such acts are directed against property or individuals, nor whether they involve physical harm or merely the restriction of the victims’ freedom.

However, the mere commission of an act of violence or coercion does not, in itself, constitute piracy. For example, an individual who kills another person on board a ship or steals his property is not considered a pirate but is instead deemed to have violated the laws governing the vessel’s flag state. Thus, for coercion to qualify as an element of piracy, it must be directed against another ship, or the ship itself must play a role—whether passive or active—in the acts that constitute piracy.[18]

Article 101 of the 1982 UNCLOS defines piracy as illegal acts of violence or detention or depredation by private ship or aircraft crew members or passengers which target vessels or aircraft or property or persons aboard in high seas areas outside state jurisdiction.

The article defines specific criminal activities that constitute piracy. Any person who knowingly participates in operating a vessel or aircraft that functions as a pirate ship or aircraft commits an unlawful act of violence. Those who provoke or deliberately help in the commission of the acts outlined in subparagraphs (a) or (b) of Article 101 face legal consequences according to this provision.[19]

2. The Material Element of the Crime of Maritime Piracy

The material element of maritime piracy consists of acts of violence or detention, or depredation, which the crew of a ship or aircraft or its passengers carry out. The 1958 High Seas Convention, together with the 1982 UNCLOS, specifically defines these unlawful acts. The illegal acts target persons and property alike, while physical injuries or freedom restrictions remain irrelevant to the definition. The critical factor remains that violent acts must be executed against a ship or aircraft that functions as the criminal instrument. The legal framework of piracy excludes attacks between individuals on board when the ship or aircraft remains uninvolved in the offense, since these incidents become flag state violations.

The crime of maritime piracy exists even if the perpetrator fails to complete the entire act since the attempt to perform the material act stands as sufficient. The material element of piracy reaches completion only when the act of piracy happens on the high seas or in territories that fall outside any state’s jurisdiction. According to international law, piracy does not exist when the act occurs in a state’s territorial sea or exclusive economic zone because the state holds full jurisdiction over these areas.

To prevent impunity, Article 101, paragraph 3, of UNCLOS criminalizes any act of incitement to commit the offenses specified in paragraphs (a) and (b), as well as the intentional facilitation of such acts. Furthermore, under Article 101, paragraph 2, liability also extends to any person who participates in the commission of acts of piracy.[20]

3. The Mental Element of the Crime of Maritime Piracy

This element is one of the most important aspects of crimes in general. It refers to the offender’s intention to commit the legally prohibited act, with full awareness and understanding of the crime and its consequences. A group of international criminal law scholars considers maritime piracy to be an intentional crime, where the criminal intent consists of two elements:

3.1 Knowledge

Knowledge refers to the awareness of the facts surrounding the perpetrator, particularly the awareness of the activity the perpetrator is about to engage in (the material element of the crime). The pirate must know that the actions they are committing constitute the crime of maritime piracy. If the pirate commits these acts while believing there is a legal justification for them, criminal intent is not present.

3.2 Intention

Intention means that the perpetrator’s will is directed toward achieving the result of their act.[21] Maritime piracy is considered a crime with multiple intents, as the perpetrator aims to steal or plunder property or goods. However, a more severe outcome may occur, such as when pirates murder the crew members, commit acts of torture, pollution, or similar crimes. In such cases, the penalty for the more serious crime is applied.[22]

4. The International Element of Maritime Piracy

The international element is a fundamental condition for the crime to be considered international. There are differing opinions in international legal doctrine regarding its nature. Due to the limitations of various doctrinal approaches in providing a precise standard free from criticism, some scholars have adopted a criterion characterized by development and flexibility, which is found in international law. This criterion is the “international interest” standard, which distinguishes between international legal actions and domestic legal actions. It is a flexible standard that aims to ensure the security, stability, and welfare of the international community.

It is notable that the crime of maritime piracy does not specifically threaten a particular state but instead threatens the security and safety of the entire international community. Therefore, it is free to describe the unlawful conduct as constituting an international crime, as it infringes upon the international interest worthy of protection under international criminal law, which is the safety of maritime shipping activities and navigation. It also poses a threat to international peace and security in the region.[23]

Section II: International and Regional Efforts to Combat Maritime Piracy

Given the severity of the crime of maritime piracy, many efforts have been made at both the international and regional levels to combat and reduce the crime of maritime piracy.

A)International Efforts to Combat Maritime Piracy

International efforts to reduce the crime of maritime piracy are reflected in the efforts of international institutions (First section) and international agreements (Second section).

1. Efforts of International Institutions to Combat the Crime of Maritime Piracy

Expressing deep concern over the growing prevalence of armed robbery and ship hijackings off the coast of Somalia in recent years, the UNSC issued several resolutions, among them the following:

- Security Council Resolution 1814 (15 May 2008, Session 5893): This resolution served as a preliminary step regarding the issue of maritime piracy. In paragraph 11, it expressed support for the contributions made by certain states and regional organizations to protect humanitarian aid convoys to Somalia. The resolution also emphasized, in its preamble, the importance of building institutions in Somalia to end violence and conflict, identifying these as the root causes of the country’s instability. Furthermore, it highlighted the Council’s intention to strengthen the effectiveness of arms embargo measures and to take action against those obstructing or undermining legitimate political processes;[24]

- Security Council Resolution 1816 (2 June 2008, Session 5902): This resolution is considered one of the most significant measures adopted by the Security Council in relation to piracy. It authorized states, for a period of six months and with the consent of Somalia’s Transitional Federal Government, to enter Somali territorial waters to combat acts of piracy and armed robbery at sea.

Exercising its authority under Chapter VII of the United Nations Charter, the Council decided in paragraph 7 of Resolution 1816 that:[25]

“States which support the Transitional Federal Government of Somalia in their anti-piracy and sea robbery operations and give prior notice to the Secretary-General can perform the following during six months from this resolution: (a) conduct operations in Somalia’s territorial waters to stop piracy and sea robbery according to applicable international law provisions for high seas operations; and (b) employ all required methods in Somalia’s territorial waters based on applicable international law provisions for high seas operations to combat piracy and armed robbery”.[26]

The Security Council passed Resolution 1838 on October 7, 2008, under Chapter VII of the United Nations Charter. It said that countries that care about maritime security need to do something about piracy on the high seas near the Somali coast. The resolution called for the use of naval ships and military planes in accordance with UNCLOS. Western and Asian naval forces heavily deployed their fleets across the Gulf of Aden under the stated purpose of fighting piracy. The deployment endangers Arab national security while potentially turning the Red Sea into an international zone, and it comes with multiple related resolutions.[27]

The Security Council issued over thirty binding resolutions between May 2008 and December 2019 concerning maritime piracy in Somali territorial waters through Chapter VII of the United Nations Charter, while declaring the situation in Somali waters as an international peace and security threat. Through this authority, the Council can assign the task of suppressing such crimes, along with armed force, to particular states. According to some legal experts, the Council took such actions and issued comparable resolutions for other worldwide matters because piracy continued to rise and created a significant hazard to maritime transport and navigation freedom, which harmed major world financial institutions and global economic systems.

The current resolutions, which started in May 2008, state that foreign military action to fight piracy needs written authorization from the Federal Government of Somalia. The Somali Transitional Government gave the United Nations Secretary-General a document that authorized specific states to chase pirates in Somali waters. The Council allows regional organizations to fight illegal activities through its resolutions. The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the European Union established two naval operations named “Ocean Shield” and “Atalanta” under this framework to fight piracy in the Gulf of Aden. The operations have maintained their presence in Somali territorial waters since their start, which marks twelve years of continuous activity.

The Security Council made its decisions regarding the Somali issue based on Chapter VII of the United Nations Charter when it reviewed the list created by the Somali Transitional Government. The Council’s coercive measures implementation requires binding cooperation from all UN Member States, although the original list submitted by the Somali Transitional Government specified only certain states. The Somali Government’s list of authorized states included a few nations, but the Council took it into account since piracy threatens international peace and security. The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda received its establishment through Council resolution in 1995, which mandated full cooperation from all states, while any non-compliance became a security threat to international peace.[28]

Multiple initiatives alongside these measures have proven effective in reducing Somali water piracy attacks, which peaked in 2011 before declining until 2017. The methods designed to fight piracy need to continue to exist, while authorities must work to enhance them as part of their strategy against piracy. The Somali scenario demonstrated the need to boost anti-piracy operations, which work on both sea and land territories. Piracy represents more than just ship attacks since it emerges from economic problems alongside social issues and weak government control.[29]

The UNSC passed multiple resolutions that dealt with maritime piracy in the Gulf of Guinea through Resolution 2018 (2011) and Resolution 2039 (2012). The Security Council under Resolution 2018 (2011) denounced every instance of piracy along with sea-based armed robbery which occurred in the waters surrounding Gulf States. The resolution expressed support for the planned summit of Gulf State leaders who would meet to create a regional security plan while urging member states and regional bodies to establish a joint strategic framework for maritime security in the region. The resolution established the necessity for regional entities to unite their efforts in providing guidance and assistance to vessels traveling through the Gulf while stressing coordination between states, regional organizations, and the shipping and insurance sectors.

The Secretary-General’s assessment mission report about Ghana’s piracy situation led to the Security Council’s adoption of Resolution 2039 (2012). The resolution established the Republic of Ghana as the main entity responsible for fighting against piracy and armed robbery at sea. The Secretary-General received instructions to assist the joint summit organization through UNOWA and UNOCA according to the provisions set out in Resolution 2018 (2011). The Security Council required UNOWA and UNOCA to provide continuous reports about piracy and armed sea robbery activities in the Republic of Ghana for the Security Council’s evaluation.[30]

The UNSC passed Resolution No. 2634 of 2022, which became effective after receiving unanimous approval from its 15 members. The Council expressed severe disapproval of all maritime piracy and armed sea robbery acts, including assassinations and kidnappings, and hostage-taking within the Gulf of Guinea. All States in the region need to include these actions as criminal offenses in their national laws while conducting investigations to prosecute and extradite those responsible. The Council demanded that all member States within the region take immediate national and regional action for the implementation of national maritime security strategies while receiving international assistance to establish a coordinated legal system that targets piracy and armed maritime crimes.

The most recent resolution on this topic was Resolution No. 2039 of 2012, which addressed piracy and armed robbery at sea in the Gulf of Guinea. The Council adopted Resolution No. 2634 as its first resolution in ten years. The Security Council adopted the resolution after six months of negotiations, which Norway and Ghana initiated as joint sponsors.[31]

The IMO, established in 1958 to facilitate cooperation and the exchange of technical information regarding ship safety and the security of those on board, has likewise been attentive to incidents of maritime piracy. Since 1980, when the IMO Council formed a working group composed of 18 States along with several other maritime organizations, the Organization has been engaged in discussions on maritime piracy and its negative impact on shipping. This working group presented a series of recommendations to the IMO Council.

In 1974, the IMO established the Maritime Safety Committee, tasked with collecting data and statistics on piracy and its geographic distribution. The Committee began receiving reports from member States and issuing comprehensive reports on piracy incidents, initially on a semiannual basis, then quarterly, and later monthly. In 1986, the Committee began following up on reports with States whose vessels were subjected to piracy, consistently urging them to submit information on incidents. Subsequently, the Committee issued Circular A.683(17), calling on governments and relevant bodies to mobilize resources for combating maritime piracy.

The IMO General Assembly passed Resolution A.922(22) in November 2001, which included the Code of Practice for the Investigation of the Crimes of Piracy and Armed Robbery Against Ships. It also included Resolution A.923(22), which included measures to stop the registration of fake ships. The International Ship and Port Facility Security (ISPS) Code was also created. It changed the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) to include rules that specifically protect ships from armed robbery and piracy.[32]

Thus, it is evident that the IMO, through its numerous resolutions, has consistently sought to combat this phenomenon. It has called upon all States to confront maritime piracy and established the Maritime Safety Committee to monitor navigational security. These efforts, combined with those of maritime offices and other international organizations, represent an ongoing global endeavor to curb this transnational crime.[33]

2. Efforts of International Agreements to Limit Maritime Piracy

International agreements are considered a source of international law and serve as legislation within the international legal system. Accordingly, maritime piracy has been criminalized based on international agreements as follows:

- Under the United Nations system, the Geneva Convention on the High Seas, signed on June 29, 1958, first criminalized maritime piracy on a contractual basis.

This convention is considered the cornerstone that laid the basic principles for the criminalization of maritime piracy in international criminal law. The convention enumerates the acts that constitute maritime piracy, and Articles 14 to 23 of the convention specifically address the criminalization of piracy on the high seas and in any area not under the sovereignty of any state, obligating the signatory countries to impose penalties on those who commit such acts.

Among others, the UNCLS, 1982, defines maritime piracy as an illegal act of violence or detention. Article 105 of the Convention addresses the concept of international jurisdiction to punish maritime pirate offenders. It says that any country may, on the high seas or in any other location beyond the authority of any other country, take any pirate ship or arrest the people on board, as well as confiscate any goods discovered on the vessel. The courts of the state that executed the seizure are empowered to rule on the property and set the penalty applied. The state also has the right to choose the method to be followed for the ships, planes, or property, with appropriate consideration to the rights of bona fide third parties. Whether on the high seas, in the territorial sea, or in international waters, these authorities include the right to seek, arrest, imprison, prosecute, and punish offenders of maritime piracy.[34]

B) Regional Efforts to Combat the Crime of Maritime Piracy

Regional initiatives against the crime of marine piracy include the Regional Cooperation Agreement on Combating Piracy and Other Unlawful Acts in Asia (First part), NATO’s activities (Second section), and the African Union’s involvement in restricting this crime (Third section).

1. The Regional Cooperation Agreement on Combating Maritime Piracy and Other Unlawful Acts in Asia (RECCAP)

The ten member states of the Asian Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), as well as China, Japan, South Korea, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh, met and signed the Regional Cooperation Agreement on Combating Piracy and Other Unlawful Acts Against the Safety of Navigation in the Asia Region (RECCAP Agreement) in response to the growing use of regional organizations for security cooperation globally since the end of the Cold War. Signed in November 2004, this agreement became operative on December 4, 2005.

The goal of this agreement, the first of its kind between countries, is to create a regional framework for coordination and collaboration between the contracting parties in order to stop and prosecute armed robbery and piracy against ships in the region’s waters. To ensure that the agreement does not conflict with the rights and obligations of the contracting states under international law, specifically the 1982 UNCLS, UNCLOS, the contracting states must implement it in conformity with their national laws and regulations.

Moreover, the exercise of this right does not provide any contracting state with the power to hunt for or stop pirates in another contracting state’s territorial seas. This clause highlights the coastal state’s exclusive legal authority over offenses like piracy and other illegal activities carried out inside its territorial waters.

According to the Regional Agreement (RECCAP), the Regional Information. In order to prevent and repress acts of piracy and armed robbery against ships, the Exchange Center was founded, with its headquarters located in Singapore. Its goal is to promote close regional cooperation among the contractual parties. Either direct bilateral collaboration between the center and the contractual parties or reference to the center’s bodies is used to carry out this cooperation.

In the fight against maritime piracy and other illegal activities against ships in Asia, especially Southeast Asia, this pact is seen as an effective example of regional collaboration.[35]

2. NATO’s Efforts to Limit Maritime Piracy

Since October 2008, NATO has conducted three maritime operations in the Horn of Africa region to provide necessary protection for ships. These operations include:

- Operation Allied Provider: Between October and December 2008, NATO launched Operation Allied Provider to protect global food aid ships passing through the Gulf of Aden and off the coast of Somalia in order to deliver humanitarian assistance to Somalia;

- Operation Allied Protector: NATO initiated this operation in 2009 to assist in preventing and disrupting pirate activity in the area, therefore enhancing the safety of international navigation and economic marine routes;

- Operation Ocean Shield: In August 2009, NATO carried out Operation Ocean Shield to assist the countries of the region, at their request, in developing their own capabilities, such as strengthening coastal patrols to combat piracy activities.[36]

3. The Role of the European Union in Limiting the Crime of Maritime Piracy

In 2021, the European Union’s efforts to combat maritime piracy included the military mission EUNAVFOR Somalia (Operation Atalanta), which concentrated on disrupting and deterring piracy, particularly off the Horn of Africa. At the same time, the UNODC’s Global Maritime Crime Programme (GMCP), supported by the EU, focused on strengthening regional capacities through legal reforms, training for law enforcement and judicial personnel, and developing mechanisms for prosecution and the exchange of evidence in affected regions such as the Gulf of Guinea.

3.1 Military measures and deterrence

- Operation Atalanta: The EU Naval Force Somalia continued its counter-piracy mission in the western Indian Ocean and off the Horn of Africa;

- Disruption: Military assets were deployed to neutralize suspected pirate groups by rendering them unable to continue their activities once intelligence reports confirmed their operations.

3.2 Capacity-building and legal support

- Judicial capacity: With EU funding, the UNODC’s GMCP supported partner states by training prosecutors and judges to address maritime crime cases, including through simulated trials and reviews of existing legal frameworks;

- Law-enforcement training: The programme provided training for maritime law-enforcement officers in surveillance, interdiction, and operational response, often through the development and implementation of standard operating procedures (SOPs);

- Legal reform: Support was extended for regional legal assessments and the preparation of recommendations aimed at improving legislation related to maritime crime;

- Cooperation: The EU also assisted in establishing Memoranda of Understanding (MOUs) to facilitate the prosecution of suspects and the transfer of evidence among states.

3.3 Regional focus and additional activities

- Gulf of Guinea: Efforts in the Gulf of Guinea were reinforced through regional initiatives such as the Yaoundé Code of Conduct, intended to address piracy, drug trafficking, and other illicit activities;

- Mediterranean: In 2021, the UNODC launched new projects to strengthen maritime law enforcement and border management capabilities in the Mediterranean, in coordination with EU initiatives such as Operation IRINI.[37]

According to UNODC’s 2023 report, EU efforts against maritime piracy include contributing to the Global Maritime Crime Programme (GMCP) and the Support to West Africa Integrated Maritime Security (SWAIMS) program, which focus on capacity-building, legal assistance, and operational coordination. These initiatives involve training law enforcement and justice officials to handle piracy cases, developing legal frameworks, and strengthening regional cooperation in areas like the Gulf of Guinea and the Horn of Africa.

3.4 EU initiatives and their goals

- Global Maritime Crime Programme (GMCP): The EU partnered with UNODC through this program to counter maritime crime. The training of more than 8,500 maritime officers from 106 nations will help develop operational skills. The plan focuses on developing better surveillance systems and response capabilities, and interdiction methods;

- Support to West Africa Integrated Maritime Security (SWAIMS): This program was designed to improve maritime security in West Africa. The program requires UNODC, together with other agencies, to provide unified regional support through the Yaoundé Architecture system;

- Capacity Building and Legal Support: A key component is strengthening the judicial response to maritime crimes through training for prosecutors, judges, and investigators. The project focuses on creating standardized evidence collection methods and enhancing prosecution success rates;

- Operational Support: The EU supports regional coordination and operational response through initiatives like the Coordinated Maritime Presences (CMP), which facilitates coordination between vessels and coastal states in key maritime areas;

- Addressing Root Causes: The EU supports efforts to eliminate piracy causes in the Horn of Africa through its backing of fishing operations and coastal villages and its support for Somali judicial institutions.[38]

According to a 2023 UNODC report, the European Union employs a multi-faceted strategy to combat maritime piracy in the Gulf of Guinea, focusing on capacity-building, financial aid, and a non-naval operational presence. The main initiatives involve regional maritime security projects funded with €55 million and legal framework development for piracy prosecution and the Coordinated Maritime Presences concept, and Yaoundé Architecture support and land-based piracy root cause solutions. Read the full UNODC report at unodc.org.[39]

4. The Role of the African Union in Reducing Maritime Piracy

Given the increasing number of maritime piracy attacks along African coastlines, particularly the Somali coast, the African Union has played a significant role by holding the 15th African Union Summit, expressing grave concern over the continuation and expansion of maritime piracy. The Union reaffirmed its support for the efforts of African states to prepare and implement a continental strategy for managing maritime navigation in Africa, as well as participating in the African force against organized crime and legal fisheries.

The Peace and Security Council held its meeting in Addis Ababa in 2010 to discuss the increasing activity of pirates. The Council reaffirmed the African Union’s commitment to strengthening and enhancing security, creating a safe and suitable environment for international fishing off the coasts of Somalia and Africa, as well as for global trade. It strongly supported the increase of the African Union mission to Somalia from 4,000 to 12,000 personnel to reduce acts of maritime piracy.

In addition, both East and West Africa have established maritime codes of conduct, which include standards for cooperation between states in combating maritime crimes. The IMO evaluated the Djibouti Code of Conduct, considering it the leading framework as it aims to encourage regional training, information exchange, and emphasizes the need for the development of national legislation. This code was developed to include not only maritime piracy and armed robbery but also any crimes that may appear on monitoring systems, such as smuggling, trafficking in illicit arms, drugs, and the sale of crude oil. In 2013, the countries of West and East Africa signed the Yaoundé Code of Conduct on Maritime Rules of Behavior in Cameroon. This code included similar legal violations with an additional obligation for its members to cooperate in maritime security through information exchange and communication with the relevant parties within the framework of the code. It also granted naval forces of those countries the authority to conduct legitimate activities, apprehend criminals, and prosecute them, while ensuring full care and attention to the maritime crew who may be exposed to crimes, with a commitment to repatriating them to their home countries.[40]

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have found that maritime piracy is one of the oldest crimes and a major issue threatening the security and safety of maritime navigation. It has evolved significantly, which has led to concerns within the international community. Maritime piracy is based on the same elements as other crimes; however, it differs from ordinary or domestic crimes in its international element.

Numerous efforts, both at the international and regional levels, have been made to combat and reduce maritime piracy. However, it continues to be widely committed in the seas and oceans.

Study Recommendations

This brings us to present the following recommendations:

- The necessity of continuing and strengthening international efforts to combat this phenomenon;

- Encouraging countries to cooperate in all matters related to ensuring maritime security for their ports and ships, to prevent them from becoming launching points for pirates;

- Establishing an international agreement specifically criminalizing maritime piracy;

- Setting binding rules for international cooperation in combating maritime piracy, including providing all available information related to the crime, as well as cooperation in the extradition of criminals.

References

Scholarly Literature:

Aamara, L. B. (2014). Maritime piracy in the Gulf of Guinea: Reality and challenges (2003–2013). Master’s thesis, University of Algiers 3, Faculty of Political Science and International Relations;

Aouacheria, R. (2011). Suppressing maritime piracy in light of international law rules: An evaluative study. Paper presented at the Third International Symposium on Maritime Disaster Management, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, October 8-12;

Attafi, M. (2020). Combating unlawful acts committed at sea. Doctoral dissertation, University of Boudaou, Faculty of Law;

Boamah, F. (2023). The role of the UN Security Council in the fight against piracy in the Gulf of Guinea. Central European Journal of International and Security Studies, 17(3);

Bouhajila, A. (2021). Maritime piracy on the high seas in light of international law of the sea. Doctoral dissertation, University of Frères Mentouri Constantine 1;

Boukjouta, F. (2013). Maritime piracy between international practice and international law. Master’s thesis, University of Algiers 1, Faculty of Law;

Bousna, A. (2014). The law of the sea and the rules applicable to ships in territorial waters. Master’s thesis, University of Constantine 1, Faculty of Law;

Fakhoury, A. (2015). International legal regime against piracy off the coast of Somalia. Journal of Law, 1;

Ghafaflia, A. Y. (2025). The efforts of the United Nations and Interpol in combating maritime piracy. Journal of Legal and Economic Research, 8(1);

Karawita, A. K. (2019). Piracy in Somalia: An analysis of the challenges faced by the international community. Jurnal Ilmu Sosial dan Ilmu Politik, 23(2);

Magsood, S. (2020). The Security Council and repression of maritime piracy: The case of Somalia. Transactions on Maritime Science, 9(2);

Mohieddine, C. (2024). Continental frameworks for maritime security protection in Africa: Ambitions and challenges. Journal of the Faculty of Politics and Economics, 22;

Omrani, N. (2013). Maritime piracy and its distinction from similar acts. Journal of Legal and Political Research and Studies, 6;

Proutière-Maulion, G. (2013). Globalization, sustainable development and human rights: The example of maritime piracy. Neptunus, 19(3);

Redha, R. D. M. A.-D. A. (2015). The role of the international criminal judge in combating the crime of maritime piracy. Journal of Law, 40;

Salimah, S. M. (2014). Maritime piracy. Riyadh: Law and Economics Library;

Sultan, M. S. (2011). Maritime security and combating piracy: Security requirements and international responses – Towards a joint international approach to combating maritime piracy. Paper presented at the Third International Symposium on Maritime Disaster Management, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, October 8-12;

Taybaoui, O., Rabhi, L. (2022). The relationship between maritime piracy and terrorism. Journal of Rights and Freedoms, 10(1);

Treves, T. (2009). Piracy, law of the sea, and use of force: Developments off the coast of Somalia. European Journal of International Law, 20(2);

Zahir Ali, J., Labaki, G. (2025). The international community’s confrontation of maritime piracy. Journal of Human and Natural Sciences, 6(3);

Zayed, A. A. (2013). Maritime piracy in international law and state applications: A case study of Somalia. University of Sharjah, Journal for Sharia and Legal Sciences, 10(2).

Normative Acts:

Convention on the High Seas. (1958). United Nations Treaty Series, 450. (Reprinted in 2005);

Maritime Safety Committee. (2021). Reports of incidents in Malacca, January 1995–January 2021. London: International Maritime Organization (GSIS);

United Nations. (n.d.). www.un.org.

United Nations, Secretary-General. (2022). Report of the Secretary-General to the Security Council: Situation of piracy and armed robbery at sea in the Gulf of Guinea and its underlying causes (S/2022/818);

United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. (December 10, 1982). 1833 U.N.T.S. 397, Art. 101. Ratified by Algeria under Presidential Decree No. 96-53 (January 22, 1996);

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. (2021). Global Maritime Crime Programme: Annual Report 2021. Vienna, Austria. https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/data-and-analysis/wdr2021.html.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. (2023). Global Maritime Crime Programme: Annual Report 2023. Vienna, Austria. https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/piracy/index.html.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. (2023). Pirates of the Niger Delta: An update on piracy trends and legal finish in the Gulf of Guinea (Part 2). Vienna, Austria.

https://www.unodc.org/documents/Maritime_crime/UNODC_GMCP_Pirates_of_the_Niger_Delta_Part_2.pdf.

Footnotes

[1] Aamara, L. B. (2014). Maritime piracy in the Gulf of Guinea: Reality and challenges (2003–2013). Master’s thesis, University of Algiers 3, Faculty of Political Science and International Relations, 29.

[2] Convention on the High Seas. (1958). United Nations Treaty Series, 450, 82. (Reprinted in 2005).

[3] United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. (December 10, 1982). 1833 U.N.T.S. 397, Art. 101. Ratified by Algeria under Presidential Decree No. 96-53 (January 22, 1996).

[4] Bousna, A. (2014). The law of the sea and the rules applicable to ships in territorial waters. Master’s thesis, University of Constantine 1, Faculty of Law, 230-231.

[5] Aamara, L. B, op. cit., 30.

[6] Ghafaflia, A. Y. (2025). The efforts of the United Nations and Interpol in combating maritime piracy. Journal of Legal and Economic Research, 8(1), 584.

[7] Attafi, M. (2020). Combating unlawful acts committed at sea. Doctoral dissertation, University of Boudaou, Faculty of Law, 37-39.

[8] Zayed, A. A. (2013). Maritime piracy in international law and state applications: A case study of Somalia. University of Sharjah, Journal for Sharia and Legal Sciences, 10(2), 169-171.

[9] Fakhoury, A. (2015). International legal regime against piracy off the coast of Somalia. Journal of Law, 1, 17.

[10] Zayed, A. A, op. cit., 170-171.

[11] Boamah, F. (2023). The role of the UN Security Council in the fight against piracy in the Gulf of Guinea. Central European Journal of International and Security Studies, 17(3), 67, 72-73.

[12] Proutière-Maulion, G. (2013). Globalization, sustainable development and human rights: The example of maritime piracy. Neptunus, 19(3), 3.