License for Polygamy and the Spread of the Phenomenon of Informal Marriage: A Comparative Study between Islamic Law and Algerian Law Supported by Judicial Statistics

##plugins.themes.bootstrap3.article.main##

Abstract

In many Arab and Islamic countries, family law historically imposed few restrictions on polygamy beyond the conditions prescribed by Islamic jurisprudence. These conditions typically included limiting polygamy to up to four wives, the ability to provide adequate financial support for each wife and a commitment to ensuring justice and equity among them.

In Algeria, family law, as established in 1984, initially permitted polygamy as the default legal framework, albeit with specific restrictions designed to prevent its misuse by husbands. Among these restrictions were the requirements for financial capability and the fair treatment of all wives. However, the law did not mandate judicial authorization for the practice of polygamy.

In 2005, the introduction of Law No. 05/02, which amended the 1984 family law, altered this provision by instituting a requirement for judicial authorization before a man could take a second wife. This change necessitated that the husband obtain permission from the president of the court in the jurisdiction where the marriage was registered.

Keywords: License, polygamy, marriage, Islamic law, Algerian law.

Introduction

In many Arab and Islamic countries, family law historically imposed few restrictions on polygamy beyond the conditions prescribed by Islamic jurisprudence. These conditions typically included a limitation of up to four wives, the ability to provide adequate financial support for each wife and a commitment to ensuring justice and equity among them. However, with the independence of Arab and Islamic nations, their membership in the United Nations, and the ratification of various international human rights conventions, the landscape of family law has evolved in line with broader societal progress.

The endorsement of international agreements, most notably the 1967 Declaration on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women and the 1979 Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) has played a pivotal role in advancing the rights of women. These developments shifted the debate from a broader international arena to more localized, national discussions within each country.

As a consequence of these changes, many Arab countries revisited and amended their family laws to ensure alignment with the principles laid out in these global treaties, thereby granting women more rights and protection under the law.

In Algeria, family law, as established in 1984,[1] initially permitted polygamy as the default legal framework, albeit with specific restrictions designed to prevent its misuse by husbands.[2] Among these restrictions were the requirements for financial capability and the fair treatment of all wives. However, the law did not mandate judicial authorization for the practice of polygamy.

In 2005, the introduction of Law No. 05/02, which amended the 1984 family law, altered this provision by instituting a requirement for judicial authorization before a man could take a second wife. This change necessitated that the husband obtain permission from the president of the court in the jurisdiction where the marriage was registered.

While this amendment aimed to regulate polygamy more strictly, it inadvertently encouraged the growth of informal marriages (unregistered marriages), as some men sought to circumvent the new judicial requirements. These informal marriages could later be formalized, raising questions about the effectiveness of the legal amendments in controlling polygamy.

The central issue raised in this context is the following: To what extent has the Algerian legislator succeeded in balancing the religious and civil aspects of polygamy through the requirement for judicial authorization? Did this measure inadvertently make informal marriage a viable alternative to polygamy? And, to what degree has it effectively safeguarded Algerian families from potential disintegration, considering that the family is regarded as the cornerstone of society?

This study aims to explore the regulatory framework governing polygamy under Algerian law and to investigate the proliferation of informal marriages, assessing whether these marriages have emerged as an alternative to traditional polygamy.

The scope of the study is to analyze the legal texts governing polygamy in Algeria, examine the legal recognition of informal marriages, and gather field data reflecting the reality of informal marriage practices in Algeria. This will include an exploration of the factors that have contributed to the spread of informal marriages following the 2005 amendment to the family law.

- Regulations of Polygamy under Algerian Law

The Algerian legislator has historically allowed polygamy as a general rule but has sought to regulate the practice through a series of legal and religious constraints designed to limit its occurrence and ensure the dignity of women and the stability of society. These regulations ensure that polygamy is not reduced to a mere transient whim but is instead treated with the seriousness it deserves.[3]

1.1. Religious Restrictions on Polygamy

Islamic law permits polygamy but sets specific conditions:

- A man may have up to four wives;

- He must be able to provide justice and financial support to each of them.

- Maximum Number of Wives

Islam allows polygamy but limits the number of wives to four. Any attempt to marry more than four is strictly prohibited, a prohibition that is well-established in the Qur’an, the Hadith, and the consensus of scholars.

As stated in the Qur’an, Surah An-Nisa (4:3):

“If you fear that you will not deal justly with the orphans, then marry those that please you of [other] women, two or three or four. But if you fear that you will not be just, then [marry only] one or those your right hands possess. That is more suitable that you may not incline to injustice”.

It is reported that Qais ibn al-Harith, who converted to Islam and had eight wives, was advised by the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) to select four of them and divorce the others.[4]

- Ability to Ensure Justice

If a man is unable to maintain justice among his wives, he is prohibited from marrying more than one, as stated in the Qur’an:

“Then marry those that please you of [other] women, two or three or four. But if you fear that you will not be just, then [marry only] one or those your right hands possess. That is more suitable that you may not incline to injustice”. (Qur’an, Surah An-Nisa 4:3)

In such a case, limiting oneself to one wife is recommended if the man fears he cannot be just, and the verse is explicit in its guidance.

The Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) also said:

“If a man has two wives and he inclines to one of them, he will come on the Day of Judgment with his side leaning”.

The justice required between wives includes matters within human control, such as providing for their food, drink, housing, kind treatment, and time spent with each.[5]

- Ability to Provide Financial Support

Islamic law restricts polygamy to those who have the financial means to support more than one wife. If a person lacks sufficient means to provide for multiple wives, it is not permissible for him to marry more than one.

The ability to provide financially is directly tied to the ability to ensure justice, as this involves the material capacity to meet the necessary conditions for marital life.[6] According to a 1987 ruling by the Algerian Supreme Court, financial equality between wives must be maintained, and each wife is entitled to her separate living accommodation.[7] However, achieving this is extremely difficult in the current social and economic circumstances.

- Legal Restrictions on Polygamy

In addition to the religious requirements, the Algerian legislator has imposed legal conditions on polygamy, including the need to provide a valid reason for the marriage, to inform both the first and the prospective wife of the marriage, and to obtain judicial authorization. These legal constraints are as follows:

- Proof of a Valid Reason

The Algerian legislator requires a man to demonstrate a valid reason for polygamy; however, the law does not clearly define what constitutes a “valid reason”. To address this ambiguity, a ministerial circular issued by the Ministry of Justice on December 23, 1984, clarified that a valid reason for polygamy must be supported by a medical certificate from a qualified doctor, confirming the wife’s infertility or a serious, chronic illness.[8]

However, after the 2005 amendment to the family law (Order No. 05/02), the previously issued circular was no longer applicable. The definition of a valid reason was expanded to include any reason provided by the husband, provided it is substantiated. Judges were granted discretionary power to assess these reasons. It is recognized that valid reasons can vary depending on the time and circumstances and may include factors such as the husband’s dissatisfaction with his wife, frequent travel leading to prolonged absences, or other personal issues.[9]

By broadening the definition of a “valid reason” and granting judges discretionary authority, there is concern that many husbands wishing to practice polygamy may hesitate to disclose the true reasons behind their decision. If the reasons are less substantial than infertility or a serious illness, proving them in court becomes challenging, which may lead to the circumvention of formal marriage through informal (unregistered) marriages, especially when judicial authorization cannot be obtained.[10]

2.2. Requirement to Inform the First Wife and the Prospective Wife

According to Article 8, paragraph 2 of the Algerian Family Law, the legislator requires that the husband inform both the first wife and the woman he intends to marry about his desire to practice polygamy:

“The husband must inform the first wife and the woman he intends to marry about his intention to marry another”. Thus, the husband wishing to marry a second wife must notify his first wife of his intention, and similarly, he must inform the second woman of his previous marriage. While the law does not specify the exact method of notification, this could likely be done through formal means, such as a registered letter with acknowledgment of receipt or via a judicial officer. In either case, the court must confirm that these notifications were made before approving the marriage.

If the husband fails to comply with this requirement, the marriage is considered to have been concluded under fraudulent circumstances, and Article 8 Bis of the Family Law allows the first wife to file for divorce on the grounds of fraud.

2.3. Requirement for Judicial Authorization by the Court President

Article 8, paragraph 3 of the Family Law states:

“The president of the court may grant authorization for a new marriage if he is satisfied that both parties agree and the husband proves a valid reason, as well as his ability to provide justice and meet the necessary conditions for marital life”.

Additionally, paragraph 2 stipulates:

“The request for marriage authorization must be submitted to the president of the court where the marital residence is located”.

From an analysis of this article, it is evident that the legislator grants the judge broad discretionary power to either grant or deny permission based on the fulfillment of certain legal conditions. These conditions include proving a valid reason for the marriage, the ability to maintain justice, and the financial means to support the marriage. Furthermore, the approval must be accompanied by the informed consent of both parties, knowledge alone is one thing, but consent is another, as confirmed by the Algerian Supreme Court in its ruling on January 19, 2005, which stated:

“Since the appellant did not prove the respondent’s consent to the second marriage, knowing about it is one thing, and consenting to it is another”.[11]

The judge must also verify the husband’s financial status and his ability to ensure justice and provide for the wives based on concrete evidence, such as a salary certificate, after conducting the necessary investigations. As previously noted, the concept of a valid reason is left to the judge’s discretion.

With all these conditions governing polygamy, the situation becomes more complex with the introduction of Article 8 Bis 01 of the Family Law, which states:

“The new marriage is annulled before consummation if the husband has not obtained the necessary judicial authorization in accordance with the conditions outlined in Article 8 above”.

From the perspective of legal interpretation, particularly through the principle of qiyas (analogy), one might wonder about the status of the new marriage if judicial authorization is not obtained after consummation. There is a significant scholarly opinion that once the marriage is consummated, it becomes valid, even without the required authorization.

This view holds that the annulment decree issued by the judge would no longer apply once the marriage is consummated.[12] This interpretation could lead to the diminishing importance of Article 8, making informal marriage (which can later be legalized) a practical solution for some couples.

- Informal Marriage as an Alternative Solution to Polygamy

Given the constraints imposed on husbands wishing to practice polygamy, many turn to informal marriage as an alternative that allows them to bypass some of these legal requirements.

3.1 Definition of Informal Marriage

Informal marriage refers to an unregistered marital contract, which takes place through a mutual agreement between the man and the woman, typically documented through a private written contract that both parties sign. While the process follows the general formalities of marriage, including witnesses, the marriage is not formally registered with the authorities or a civil registrar, which is a legal requirement under Algerian law.[13]

As per Article 18 of the Family Law: “Marriage is contracted before a notary or a legally authorized official, in accordance with the provisions of Articles 9 and 9 Bis of this law”.

Furthermore, Article 4 of the same law states: “Marriage is a consensual contract between a man and a woman, conducted according to the religious law”.

Article 22 adds: “Marriage is established through an extract from the civil status register. If not registered, it is validated by a judicial ruling. The judicial ruling must be registered in the civil status register by the efforts of the public prosecutor”.

From the interpretation of these provisions, marriage is fundamentally a consensual contract, and the formal requirement is for its proof, not its formation. If a marriage is not registered despite fulfilling the essential conditions, any interested party can prove the marital relationship before the court based on Islamic jurisprudence. This is known as informal marriage.[14]

3.2. Informal Marriage as a Refuge for Those Seeking Polygamy

The Algerian legislator has imposed strict regulations on polygamy, requiring prior authorization from the president of the court in the jurisdiction where the marital residence is located. This measure is designed to provide legal safeguards, primarily to protect women’s rights within the institution of marriage. However, these stringent requirements have driven many individuals to seek alternative solutions, resulting in a significant rise in informal marriages, particularly after the amendments to the Family Law in 2005, especially those concerning Article 8.

Despite the mandatory requirement for mosque imams to refuse to officiate any marriage without a civil marriage certificate, an attempt to curb the rise of informal marriages, this prohibition has been largely ineffective. The disparity between the number of authorized polygamous marriages and informal marriages underscores this challenge.[15]

Statistics from the registry office of the Ain Témouchent Court reveal a troubling trend: between 2008 and May 2018, the court president issued only fifty judicial authorizations for polygamy. In contrast, during the same period, 1,350 cases were recorded for the recognition of informal marriages.[16]

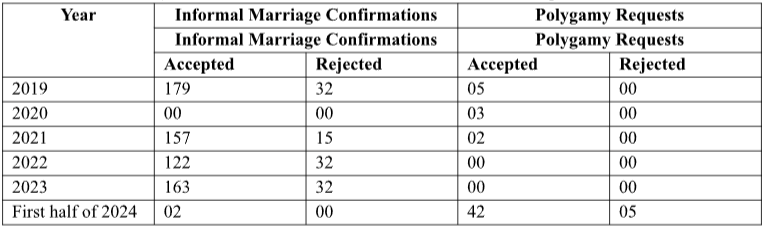

More recent statistics (from 2019 to the first half of 2024) show a continued pattern:[17]

An analysis of these statistics clearly shows that the number of recognized informal marriages consistently outnumbers the approved polygamy requests. This highlights a marked preference for informal marriages, likely driven by the bureaucratic hurdles and legal restrictions surrounding formal polygamy.

In these informal marriages, it is common for the second wife to eventually file a petition to officially recognize the union. This legal recognition enables the first wife to file for divorce, as polygamy is considered a valid ground for divorce under Article 53 of the Family Law.

Thus, the law, intended to restrict polygamy, has inadvertently fueled the rise of informal marriages, as individuals circumvent the formal requirements. Once the informal marriage is recognized through judicial intervention, it is formally registered in the civil status records by the public prosecutor, granting the second wife the same legal rights as if the marriage had been officially recognized from the outset.[18]

The Algerian Supreme Court further reinforced this understanding in its ruling of 1991, affirming that:

“Whenever an informal marriage meets all the necessary conditions and requirements, the court’s decision to validate this marriage, register it in the civil status records, and legitimize the children born from it is consistent with both Islamic law and the civil code”.

The Supreme Court’s rulings have established that informal marriages can be legally recognized through testimony from relatives, two male witnesses, or one male and two female witnesses. However, it is not permissible to establish the validity of a marriage based solely on the testimony of two women or a single witness.[19]

Additionally, one of the witnesses cannot be the legal guardian of the woman involved in the marriage. Importantly, there is no time limit for recognizing informal marriages, and such unions can even be validated after the death of one of the spouses, provided sufficient testimony and an oath are presented.

For the court to accept witness testimony, the witnesses must demonstrate that they were present at the marriage contract, the reading of the Fatiha (the opening chapter of the Quran), or at the marriage celebration and that their testimony is consistent with other available evidence. Judges are required to conduct thorough investigations to verify the facts, as rejecting a claim to confirm a marriage stemming from an illicit relationship is considered a sound judicial decision.[20]

Conclusion

The Algerian legislator, through the amendment of the Family Law by Order No. 05/02, has narrowed the scope of polygamy to protect women’s rights and preserve family stability. However, the focus has been primarily on safeguarding the rights of the first wife, overlooking the rights of the woman the husband intends to marry. If the husband cannot obtain the required authorization, informal marriage often becomes the alternative. This is particularly true in light of Article 08 bis 1 of the Family Law, which annuls a marriage before consummation if performed without the necessary permission, suggesting that after consummation, the marriage can only be later proven and registered.

Since the 2005 amendment, informal marriages have risen significantly, and these unions are increasingly brought before the courts for official recognition. This undermines women’s dignity, stripping them of basic rights like alimony, public benefits, inheritance, and other legal protections. The effects also extend to children born from informal marriages, who lose rights typically afforded to those born from formal unions, such as inheritance and familial rights.

Based on the above, we recommend the following:

- The legislator should consider religious principles underpinning the state and allow polygamy within Sharia law limits. Restricting polygamy may lead to an increase in illicit relationships, resulting in harmful consequences, especially concerning children and lineage. The European model, which prohibits polygamy, cannot be a suitable comparison given Algeria’s religious and cultural context;

- Annulments before consummation in polygamous cases without judicial authorization contradict Sharia principles if the marriage meets the essential requirements within Sharia law;

- Authorities should launch awareness campaigns to reduce informal marriages and illicit relationships. These practices negatively affect family and community stability and security.

Bibliography

Academic Articles:

- Omaran, F.M. (2005). Informal Marriage and Other Forms of Unofficial Marriage. Modern University Press, Alexandria.

Academic Articles:

- Mohamed Boumediene, The Authority of the Judge in Granting Permission for Polygamy: A Comparative Study, published online: https://platform.almanhal.com/Files/2/40548.

- Chouar, D. (2010). Legislative Gaps in Family Law Regarding Some Marriage Issues: Legal or Judicial Justice? Journal of Legal, Administrative and Political Sciences, Issue 10, Faculty of Law and Political Science, University of Abou Bakr Belkaid, Tlemcen.

- Cheikh, S. (2017). Informal Marriage as an Alternative Solution to Polygamy. Presentation delivered at the study day titled Family Law between Legal Phenomena and Social Deficiencies, Mediterranean Center for Legal Studies, University of Abou Bakr Belkaid, Tlemcen.

Theses and Dissertations:

- Mehdawi, H. (2009/2010). A Critical Study of the Amendments to the Family Law Regarding Marriage and Its Effects. Master’s Thesis in Family Law, Faculty of Law and Political Science, University of Abou Bakr Belkaid, Tlemcen,

- Addadi, S.E. (2015/2016). Polygamy: Unlimited or Restricted? Master’s Thesis in Family Law, Faculty of Law and Political Science, Dr. Taher Moulay Saida University,

Legal Texts:

- Order No. 84/11, dated 09.06.1984, Family Law, amended and supplemented by Order No. 05/02, dated 27.02.2005.

- Ministerial Circular No. 84/102, issued by the Ministry of Justice on 23.12.1984, detailing the implementation of Article 8 of the Family Law.

Judicial Decisions:

- Supreme Court Decision, Family Affairs Chamber. (1990). Case No. 45311, issued on 09.03.1987, Judicial Magazine, Issue 3.

- Supreme Court Decision. (2005).Dated 19.01.2005, published in the Supreme Court Journal, Issue 1.

- Supreme Court Decision, Family Affairs Chamber. (1991). published in the Judicial Magazine, Issue 4.

Footnotes

[1] Order No. 84/11, dated 09.06.1984, Family Law, amended and supplemented by Order No. 05/02, dated 27.02.2005.

[2] Article 8 of the Algerian Family Law.

[3] Addadi, S.E. (2015/2016). Polygamy: Unlimited or Restricted? Master’s Thesis in Family Law, Faculty of Law and Political Science, Dr. Taher Moulay Saida University, p. 10.

[4] Cited in Addadi, S.E., Op. cit., p. 9.

[5] Addadi, S.E., Op. cit., p. 11.

[6] Chouar, D. (2010). Legislative Gaps in Family Law Regarding Some Marriage Issues: Legal or Judicial Justice? Journal of Legal, Administrative and Political Sciences, Issue 10, Faculty of Law and Political Science, University of Abou Bakr Belkaid, Tlemcen, p. 114.

[7] Supreme Court Decision, Family Affairs Chamber. (1990). Case No. 45311, issued on 09.03.1987, Judicial Magazine, Issue 3, p. 61.

[8] Ministerial Circular No. 84/102, issued by the Ministry of Justice on 23.12.1984, detailing the implementation of Article 8 of the Family Law.

[9] Cheikh, S. (2017). Informal Marriage as an Alternative Solution to Polygamy. Presentation delivered at the study day titled Family Law between Legal Phenomena and Social Deficiencies, Mediterranean Center for Legal Studies, University of Abou Bakr Belkaid, Tlemcen, p. 2.

[10] Cheikh, S., Op. cit., p. 3.

[11] Supreme Court Decision. (2005). Dated 19.01.2005, published in the Supreme Court Journal, Issue 1, p. 325, quoted in Sheikh, S., Op. cit., p. 5.

[12] Cheikh, S., Op. cit., p. 5. See also Mehdawi, H. (2009/2010). A Critical Study of the Amendments to the Family Law Regarding Marriage and Its Effects. Master’s Thesis in Family Law, Faculty of Law and Political Science, University of Abou Bakr Belkaid, Tlemcen, p. 64 and onwards.

[13] Omaran, F.M. (2005). Informal Marriage and Other Forms of Unofficial Marriage. Modern University Press, Alexandria, p. 25.

[14] Cheikh, S., Op. cit., p. 6.

[15] Addadi, S.E., Op. cit., p. 60.

[16] Information obtained from the Registry Office of Ain Temouchent Court.

[17] Data derived from the Statistical Office of the Ain Temouchent Judicial Council, specifically from Ain Temouchent Court.

[18] Addadi, S.E. Op. cit., p. 61.

[19] Supreme Court Decision, Family Affairs Chamber. (1991). published in the Judicial Magazine, Issue 4, p. 50, referenced by Cheikh, S., Op. cit., p. 8.

[20] Cheikh, S., Op. cit., p. 8, citing a series of decisions issued by the Family Affairs Chamber of the Supreme Court.

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6665-6510

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6665-6510