CRUISING DOWN THE STREETS OF JUDICIAL DISCRETION: CONSTRUING THE EQUITABLE RELIEF IN COMMON-LAW BANGLADESH

##plugins.themes.bootstrap3.article.main##

Abstract

Anizman Philip states that discretion starts at the dusk of law and has the potential to inflict justice and injustice. The legal realm of common-law Bangladesh historically evolved from stare decisis, which is mostly discretion in the conventionally accepted form. To better understand, specific reliefs, statutory interpretation, grant of bail in a non-bailable offence, and so on are discretionary equitable reliefs. This empirical qualitative study was conducted to expound the undefined concept of judicial discretion, its curb and extent, its possibility of misuse, and its application in the judiciary. Through this study, it has been settled that the scope of the misapplication of discretionary power is comprehensive. External factors such as the good character of a litigant influence discretionary decision-making immensely. Discretion is to courts like water is to a fish. It is inherent, whereby it finds its silver lining in ex debito justitiae. The scope of discretion is voluminous; thereby, greater are its concerns.

Keywords: Court’s Discretion; Judicial Discretion; Discretionary Jurisdiction; Discretionary Power; Suo Moto.

- Introduction

‘When law ends, discretion begins, and the exercise of discretion may mean either beneficence or tyranny, either justice or injustice, either reasonableness or unreasonableness.’[1]

Anizman Philip

Conceptually, discretionary jurisdiction is deferred statutory authority on judges[2] to evaluate facts within the premise of principles laid out by law,[3] especially at the juncture of a dilemma between multiple valid courses of action.[4] Whereby the doctrine of balance and comparative analysis is applied between various legal principles to determine the significance, relevancy, and applicability of each principle to a particular case[5] in order that conclusive outcomes forwarding justice are excavated wherever the use of such discretionary power is legislatively permitted.[6] Speaking of being statutorily allowed in Bangladesh, such notion is provided by any enactment containing phraseologies such as ‘the Court may suo moto,’ ‘as the Court otherwise directs,’ ‘as the Court deems proper,’ ‘as the Court thinks reasonable,’ etcetera[7] or confers discretionary power by the discreet use of the jargon. Courts electing to manifest such discretionary jurisdiction can base its decision on stare decisis or on established principles, policies, or prudence, on rights or relationships between an individual and state, identities,[8] which on an important note must be reasonable, logical, and probable based on bonafide deductions of facts to secure justice.[9] The perception that discretion strategically extends jurisdiction is not invalid. However, the preference lies on the broader prospect that discretion is jurisdiction itself,[10] extending to civil and criminal proceedings and private and public laws.[11] Furthermore, Court’s discretionary power in Bangladesh is not constrained to the provisions of law. It, however, relies heavily upon and extends its exercise on sound judicial principles.[12] Griffith (1994), in his report providing guidelines for sentencing and judicial discretion for the then Australian Government, delineated discretion, stating that arbitrariness in decision-making could be vanquished by deliberating policy on a requirement basis to promote confidence between the state and its subject through belief in the fairness of the process.[13] Numerous instances call on discretion to resolve a dispute (Fletcher, 1984).[14] In Bangladesh, neither such instances nor the term ‘discretion’ has been expounded, and its parameters have been undefined.[15] This study identifies and expands the concept of discretion, its scope of misapplication, its reach and curb, and its applications in the courtroom.

- Problem Statement

History is irrefutably evident that the independence of the Judicial Organ of Bangladesh exists only on paper. The organ of last resort is overshadowed by the executive authority of the Ministry of Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs, exercising exorbitant control over all its affairs like appointments, promotions, administration, dismissals, training, etcetera.[16] In the Government of Bangladesh v Advocate Asaduzzaman Siddiqui[17] popularly known as the 16th Amendment Case, the obiter dictum of the Appellate Division recognized that the constitutional responsibilities conferred on judges could not be performed diligently, with ease of mind, unless the judicial organ is separated completely in its truest sense. Surprisingly, the Masdar Hossain case relating to the independence of the lower judiciary has been called on for review to establish a balance of power by the finance minister.[18] Time has sufficiently disclosed that political variables and affinity towards wealth, displayed mainly through the ascension of the judicial hierarchy, disproportionally influence a judge’s discretion.[19] In compliance with such, claims that the judicial organ of Bangladesh is incoherently politicized suffice the antagonism and distrust between the two dominant political parties of the State. Furthermore, elevation in judicial ranks is a product of the political discretion of the ruling party. Hence, such political discretion demands favours of judicial discretion from the elected appointees.[20] In respect of the above, the statement by Anizman Philip comes to mind as the variables directing the path of discretion are likely to invite unreasonableness and recur tyranny and injustice. Therefore, it is essential to reveal how the undefined discretionary jurisdiction of the Court functions. In Bangladesh, civil reliefs are moderated by the discretionary power of the Court, admissibility of evidence, permissive judicial presumptions are discretionary, and procedural aspects, both civil and criminal, allow discretionary intervention.

- Aims and Scope

It has already been established hereinbefore that the concept of discretion and its parameters have not been defined in Bangladesh[21] and without definite standards lies the risk of discrimination and misapplication[22]. Considering such, this research undertakes to enlarge the followings viz.

- Expound the Concept of Discretion,

- Analyse the Equitable Relief factor of Discretionary Jurisdiction.

- Explore the probable misapplication of Discretionary Jurisdiction.

- Study the Applications of Discretionary Power in the Courts of Bangladesh.

- Investigate the limits of discretionary jurisdiction.

Not much work has been done on the current topic from the perspective of Bangladesh and since judicial discretion covers a wide array of legal affairs, hence, this study entices social prominence within the prospect of law.

- METHODOLOY

The course of this study is empirical, whereby the qualitative data analysis approach was adopted to extract its results. A qualitative study deploys in-depth scrutiny en route revealing the relevant interconnection and interdependency between concepts.[23] Primary and secondary documents, e.g., relevant scholarly articles, news reports, relative laws of Bangladesh like the Specific Relief Act of 1877, the Code of Criminal Procedure 1898, the Code of Civil Procedure 1908, and reports of local and international organizations, was extensively studied and analyzed. It is well-settled that Bangladesh regulates within the legal system of the common law.[24] Wherein any decision of the Apex Court not subjected to per incurium by the same division gracefully maintains the status of stare decisis.[25] Moreover, the law declared by the Apex Court extends an irrebuttable binding effect on all other Courts inferior to it.[26] Keeping the doctrine of stare decisis and practical approach in mind, law journals, decisions of higher Courts of Bangladesh, and other countries relevant to the scope of this research have been elaborately analysed.

- RESULTS & DISCUSSIONS

This study embarked on the journey to elaborate on the notion of discretion, and it is an equitable relief. This study also set out to discover the probable scope of misapplication of discretionary jurisdiction, its limits, and applications within the judicial system of Bangladesh. The following sections attend to all those queries.

- Expounding Discretion

Imagine a crossroad, and each road presents itself as a viable travelling option. Like the crossroad, discretion empowers a judge to opt and choose between alternative options, and each option is viable and lawful.[27] State v Hazi Osman Gani[28] narrowed the crossroad of discretion to distinction evolved from one's conscience and judgement of facts parallel to the statutory guidance between right and wrong. In a broader sense, discretion implies freedom of conscious choice.[29] The legal standpoint of judicial discretion is best depicted and understood via the doughnut theory, i.e., like the hole in the doughnut, judges may only elect to exercise discretionary jurisdiction on instances where legislative loophole or scope for such exists.[30] The solid dough represents the guidelines of such jurisdiction, or better, the constraints of it.[31] Considering the solid dough, the frosting is served best when the discretion is sound and sprinkled with the combination of non-arbitrary, reasonable, and lawful stance as the toppings.[32] On another note, discretion is delegated authority conferred as an aid to draw substantive and procedural decisions,[33] especially on occasions when circumstantial fairness demands action by the Court given a litigant is disentitled to such as a matter of right.[34] Furthermore, judicial discretion plays an integral role in dispensing justice.[35] Given that discretionary power is founded on a judge's individual judgment and conscience, subject to general and special limits. Therefore, discretionary jurisdiction acts as an element of the legal status of a judge within the norms of duties and responsibilities.[36] According to Hart, discretionary jurisdiction, like precedent and legislation, potentially relates to a credible source of law.[37] Figure 1 depicts the various statutorily allowed discretionary provisions of Bangladesh.

- Discretion & It’s Principles

According to Bushway and Forst (2013),[38] discretion is appraised on outcomes anticipated to be generated from it, as the employment of discretionary jurisdiction is moulded of rules and obtained as a by-product of extensive inquiry. Such by-product of substantial inquiry is categorized into two specific ideologies, i.e., primary discretion and secondary discretion. The former allows a greater array and independence of choice, which is the general undertaking of the subject by professionals and academics of law. On the other hand, the latter is restricted mainly by rules and principles, thus permitting criticism of the correctness of such discretion.[39] In re above, it is apparent that secondary discretion governs judicial prudence in Bangladesh. Navigating further into the categorization, given the established grounds that discretion in Bangladesh is secondary, i.e., it is subjected to rules and generated as a result of judgement and bonafide conscience. Discretion and legal approach to rules can be correlated by delimiting a precise line of variation between discretion and judicial conduct regulated by rules and legislations.[40] Conceding to the above, discretion does not exist independently but with rules to exert intra-vires and is structured according to policy[41] or to deter from being a threat to the rule of law[42] or a technical unnecessity. Such scourges of discretionary jurisdiction exist based on its prospective of being deployed capriciously and arbitrarily.[43] Moreover, Kotskulych[44] proposed a few elite canons of judicial discretion and its functionality, viz.

- Principle of Justice:

provides the Court with the challenge of choosing from evidential information provided by litigants.

- Principle of Pragmatism:

The Court must obviate from jumping to any conclusion without scrutiny and conclusion of proceedings.

- Principle of Devising:

The presiding judge must weigh between evidence based on its significance to the matter presented.

- Principle of Professional Optimism:

The Court must adhere to the corresponding legislation in an effort to promote faith in it.

- Principle of Prudence:

The Judge must decide to apply bonafide conscience, knowledge and skill specific to the situation, justified by law with due regard for moral values, rationality and legal actuality.

- Principle of Dynamic Acclimatization:

The Court presiding must be equipped with skilful and prompt knowledge to implement legal proceedings.

- Principle of Ethical Accountability:

The Judge must assume to assist the moral demands of society and differentiate between social right and wrong and decide considering human emotions.

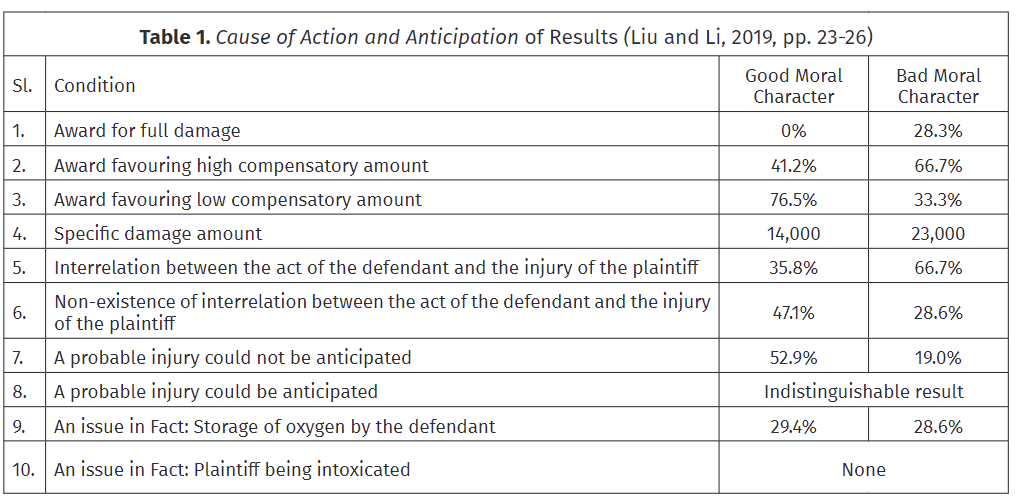

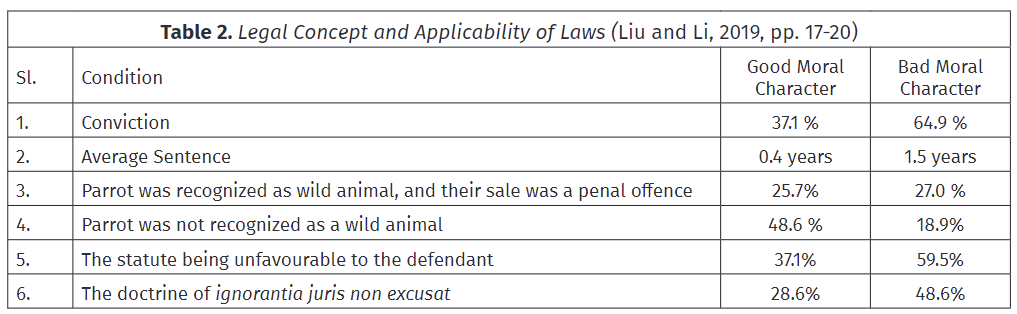

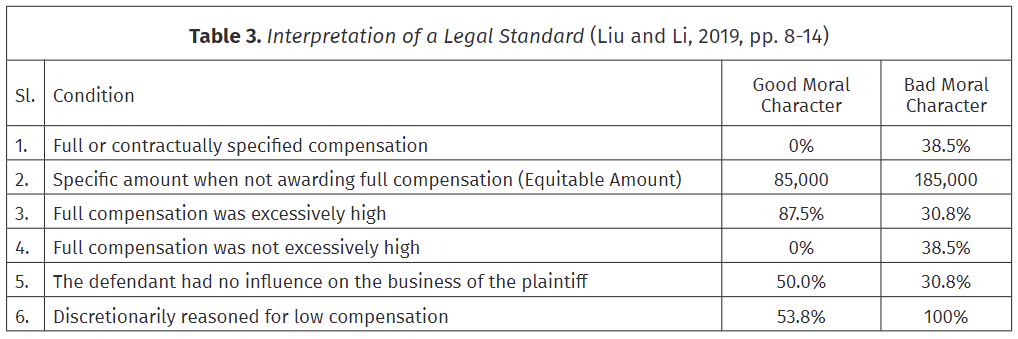

Liu and Li devised an experiment forwarding stimulated questionnaires to judges on the subjects of a cause of action and anticipation of results, legal concept and applicability of laws, and interpretation of legal standards to be discretionarily decreed. The experiment was designed around two distinct categories of defendants, viz. defendant of good moral character and defendant of bad moral character[45] (hereafter numerically represented in that respective order). Though, the character and morals of a litigant are nugatory aspects of the law. However, the results cumulated were auspicious and are tabulated below:

In the study on the cause of action and anticipation of results, the scenario presented to the 38 participant judges was a claim for medical damage resulting from injuries incurred on the plaintiff from attempting to extinguish a village fire caused by the explosion of oxygen tanks. In contrast, the plaintiff was intoxicated by alcohol. Only one participating judge applied the reasoning of character. The results, however, speak for itself.

The test on legal concepts and applicability of laws dealt with an endangered parrot. Out of the 72 participating judges, only 1 ruminated the character of the defendant in the decision.

This study presented a classic example of a delay in the performance of a contract. The scenario was that a rental contract for two units was established between the lessor and the lessee containing a specific amount of damage. The delivery of possession was delayed two days prior to the move-in date. The plaintiff's claim was the specified amount due to incurred loss of business and the shifting expenses, while the defendant argued that the liquidating damage was excessive.

This study's pertinence to the Bangladeshi legal scenario is prominently immaculate, relating to the fact that judges in Bangladesh account for the character, social status, previous criminal history, etcetera., of the litigant while employing discretionary jurisdiction.

- Equitable Relief

It has been determined beyond every query that a Judge is empowered via the statutory incorporation of the phrases ‘the Court may suo moto,’ ‘as the Court otherwise directs,’ ‘as the Court deems proper,’ ‘as the Court thinks reasonable,’ etcetera to apply discretionary jurisdiction.[46] Whenever a Judge commits to employ such legitimized discretionary power, it must ascertain that the use of such discretionary power expediate lawfulness and fairness via comprehensible judicial act and must not be a substitute for judicial arbitrariness.[47] A comprehensible judicial act denotes acquiring a solution that displays a direct juridical link, justice, accuracy, justifiability, and rightness[48] as justice must not only be done but must also be seen to have been done.[49] Adhering to constitutional principles is the perfect example of a direct juridical link.[50] Courts are the connectors of the missing link and possess the potential and responsibility to bring constitutional and democratic principles to task by reviewing the arbitrary use of discretionary power.[51] Arbitrary or fanciful use of discretionary power must be evidenced in Court for it not to be overturned.[52] According to Wright and Davis, discretionary decision-making allows flexible empirical growth of the common law by extending the scope of procedural fairness.[53] Thereby, judges could impose procedural obligations of consultative nature on the legislature[54] and not ignoring the fact that common law is judge-made law, i.e., law formulated from the knowledge, understanding, and discretion of judges. On every instance a Court elects to utilize discretionary jurisdiction, it acts as a Court of Equity. It, therefore, must conform not to deliver any of the parties into a position of undue advantage over the other,[55] it must also conform conduct of the parties, i.e., the willing performance of the committed transaction as equity repudiates to remedy the one that aids to the impossibility of performance.[56] It is unethical to demand a remedy after callously forcing a situation into the dark room of intervening impossibility. The maxim ex turpi causa non oritur actio, i.e., the fraudulent behaviour of a man cannot be the basis of an action,[57] comes to the rescue. Discretionary equitable relief attempts to solidify justice by practicing freedom of circumscribed choice to implement conscious judicial functions.[58] Additionally, a conscious judicial functioning is more of an equilateral balance between awareness and action, i.e., the litigants are vigilantibus non-dormantibus jura subveniunt, i.e., the litigants are aware of the rights and laches and vigorously assert their rights as equitable relief only comes around when such conditions are uncompromised.[59] A notable example of such would be any objection relating to the usage of discretionary jurisdiction must be raised at the earliest possible occasion, as discretionary jurisdiction, once exercised unobjected, cannot be meddled with simply due to the availability of alternate efficacious remedy.[60] In Bangladesh, equity governs the rights of parties[61] and embodies discretionary equitable relief. For example, the common law courts in the country preside on matters relating to evidence, i.e., its relevancy, admissibility, granting or refusing an injunction, specific performances, amount of alimony, grant or refusal of bail, etcetera., at its discretion.[62] Furthermore, equitable reliefs hold the factor of time to high prospect notwithstanding the inclusion or exclusion of a specified time clause. It requires the completion of every agreed-upon task within a reasonable span. However, the inclusion of time constraints and the intent to treat it as the essence of a contract may displace the presumption provided such is evidenced by circumstances.[63] In Bangladesh, statutes like the Specific Relief Act of 1877, the Limitation Act of 1908 equitable grant relief. The Specific Relief Act formally makes mention of the discretionary aspect of its execution. On the other hand, the Limitation Act strives to eliminate laches and maintain ease of procedure whereby the calculation of the time is discretionary, e.g., in Akbar Ali v State,[64] it was held that working days of the court are the days on which the court officially sits that excludes all public holidays and private leaves, condonable delays supported by reason, etcetera.[65]

- Limitations & Scope for Misuse

In Government of Bangladesh v Advocate Asaduzzaman Siddiqui,[66] the Apex Court held that the malafide exercise of discretionary jurisdiction attracts nullity, amounts to abuse, and is bad in law. Adding to the obiter dictum of the Apex Court, however much it is argued upon, discretion occupies a part in the various legal systems based on the recourse of subjecting it to the plethora of control.[67] The undeviating correlation between limitation and scope for abuse MUST NEVER be overlooked, as when limitation exhausts, abuse engages. Relating the previous concept to the doughnut analogy, it is safe to consider that discretion is illusory except when an opening is visible.[68] Concurring therefrom, a defined minimum standard must adhere to eliminate decisional autonomy[69] or discriminative/ prejudiced application of statutorily empowered discretionary jurisdiction.[70] Such exists under the presumption that provisions of law regulate society as a unit and that discretion is an individualized opinion susceptible to influence.[71] To address susceptibility to influence the human nature of the judges must not be ignored. Higgins & Rubin (1980) experimented on the Eighth Circuit district court judges, therein, the presumption of enforcing values on society through presiding over landmark judgements, human inclination to a particular party, urge to accumulate wealth in the form of professional accolades, political views, etcetera., were shown to relatively influence discretion.[72] Discretionary jurisdiction, when mathematically considered, represents a probability dependent on personalized overviews, with the upper limit being equity and the lower limit being due regard for the conferring statute.[73] A set of ground rules to contain the arbitrary deployment of judicial discretion proposed by Azarova were viz.

- Opportunities provided to judges are based on the commitment to resolve questions according to the provisions of the law.

- providing reasonable argument as to the solution of a question of law with clarity

- opportunities to fill existing gaps in the law

- moral and professional etiquette of the judge[74]

Somehow, discretion is always shaded under the agape criteria of good faith.[75] The pursuit of upright judging is essentially the quest for unbiassed principles,[76] i.e., sound discretion guided by law, reason and logic.[77] In those spirits, constitutional doctrines such as nondelegation and nullity for ambiguity vitally chain down abuse of discretionary power.[78] The maxims optima lex quae minimum relinquit arbitrio judicis and optimus judex qui minimum sibi, i.e., law is best when it leaves least to judicial discretion as unregulated discretionary jurisdiction of a judge is deemed ‘law of the oppressors’ by Spindle on the accounts of human shortcomings.[79] To better understand, the notion of expanding discretionary authority stands contrary to the doctrine of precedent as untamed discretion does not bind a judge to text or stare decisis;[80] e.g., the principle of per incurium and its applicability is confined only to err in law.[81] Similarly, an exercise of discretion is reversed when such is abused or stands contrary to ordinary prudence or sound judgement.[82] In re arbitration, a judge may expand the discretionary horizon subject to the approval of the parties of the arbitration[83] which, however, en route judicial proceeding is constricted within the laws of evidence.[84] In conclusion, to avoid discretion from presuming tyranny, unfettered unnecessary discretionary power should be eliminated.[85]

- Interpretation

The interpretation of statutes indeed requires discretion,[86] knowledge of the laws, etcetera., while following the guidance of the widely prevalent cannons of construction. Discretion finds its silver lining in statutory interpretation when broad scenarios such as ‘good faith’ are present in the picture, which without failure, affect the content and the sought outcome.[87] For example, the concept of good faith is mentioned numerously in the General Exceptions chapter of the Penal Code (1860). Furthermore, judicial discretion pays homage to its roots when it comes to interpretation pertaining to the fact that plural legal development is probable.[88] It is settled that a right to review legislature also exists as a suo moto rule. In the United States, Courts apply the arbitrary and capricious test primarily focusing on procedural violations when reviewing administrative rulemaking,[89] as a judge’s discretion to interpret the law is directly proportional to legal indeterminacy.[90] The concept of indeterminacy of law finds its causes in incomprehension, i.e., the availability of multiple referrable legal materials and ambiguity of language preferred in the legislation.[91] The decision of Gias Kamal Chowdhury and others v Dhaka University and others[92] dictates negating all alternative remedies when the interpretation of the law is involved as discretionary jurisdiction of interpretation exists with high aspirations to help diminish vagueness, ambiguity or contribute to eradicate indeterminacy of law and not add to it.[93]

- Evidential Discretion

The laws of evidence in Bangladesh assert greater responsibilities on judges as evidence naturally regulates the pathway of any litigation. Consider the doctrine of res gestae as an example; it demands materiality of time, place, and event; however, no definite standard can be formulated for applying such principle.[94] Significant aspects such as the admissibility of evidence or a witness, presumption of the existence of a specific material fact, etcetera., are direct products of discretion. This section contemplates such grounds related to evidence.

- Admission

The admissibility of any evidence depends on the test of relevance or its relation to the fact in issue, i.e., every form of evidence preferring admission must either be relevant or be related to the fact in issue.[95] While determining the relevancy, relation to fact in issue, or eligibility of evidence submitted to be placed on record,[96] the Judge must exercise discretion with utmost caution while having consideration of the possibility and consequence of error.[97] It is commendable to address questions related to admissibility as it is encountered[98] as an effort to preserve time.[99] Section 136 of the Evidence Act (1872) explicitly mentions the prospect of discretion transpiring upon admission of evidence. The provision uses the phrase ‘if the judge thinks’ the fact aspired to be proved would be relevant, applying the same condition on the relevancy of the asserted fact. Government of Bangladesh v Amikun [100] held that re-examination is allowed by the exercise of discretionary jurisdiction, permitted specifically to clarify or introduce evidence. It is settled that admission raises presumption, which generates an adverse reaction on the burden of proof on the opposition, hence, establishing the substance of admission of evidential components.

- Presumption

It is conclusive that judicial presumption causes Courts to incline towards the party favoured with such presumption. The comprehensive scenario of evidential presumption effectuates either,

- rebuttable mandatory presumption of law designated using the word ‘shall presume,’[101]

- permissive rebuttable presumption of fact employing the word ‘may presume,’[102]e., the scope of this study.

Contradictory views of the obligatory nature of rebuttable mandatory presumption have been expressed vide Bangladesh Water Development Board v GA Faiyaz Haider.[103] The legislative intent behind using such phraseology is to allow the passage for discretion.[104] However, such is confined to the ordinary course of events, human nature,[105] and the existence of any fact that intrigues the judicial mind to likely have happened subject to relevancy to the specific case.[106] Considering a few examples, every piece of legislation is judicially presumed to be reasonable and errorless,[107] documents such as letters, notices, and summons sent by the registered post containing the correct address of the recipient, even when refused is presumed to have been duly served,[108] etcetera. The implications of the permissive rebuttable presumption of fact are analysed hereinafter, keeping Section 114 of the Evidence Act as its focal point.

- Suits of Civil Nature

Rebuttable presumptions are directing arrows guiding on whom the onus of proof lies, which on being addressed by the concerned party with reasonable evidence, eliminates such presumption.[109] The law dictates, as of principle and prudence, that all pertinent facts must be stated in the prosecution or defence by the respective parties.[110] The argument behind such is that evidence cannot be adduced at a later stage. Unless such has been declared in the pleadings[111] or the pleading has been amended lawfully for such evidence to be entertained.[112] Regarding pleadings, every positive assertion made therein must be denied explicitly by the opposition as the failure of such raises the presumption of admittance of every undenied allegation.[113] Keeping in mind that every denial must be precise and not elusive[114] to such a degree that withstands the significant judicial deduction against non-denial as courts do not entertain any question on the related subject at any later stage.[115] Dayal Chandra Mondal v Assistant Custodian, ADC (Rev) Dhaka[116] directed the Courts below to abstain from dismissing suits resorting to abstract assumptions, especially when the defendant fails to deny the assertions of the plaintiff specifically. Permissive presumptions exist to save procedural time[117] as it occasions to centre its focus on substantial proof against it, e.g., publications in the official gazette such as a list of abandoned buildings,[118] abandoned properties, etcetera,[119] are presumed correct unless the contrary is proved by substantial evidence because abandonment relates to deserting possession of the property. Possession of the same subject fosters the presumption of ownership in favour of the person in possession of the property,[120] provided the possession is neither prima facie proscribed nor is the title proved against such possession.[121] A defective title is good against all, but the true owner who asserts proprietorship of such property via evidence[122] as such presumption is always rebuttable.[123] In the suit of GM Bangladesh Railway v Sharifjan Bibi[124] the rebuttable presumption of the RS record was cast aside on the submission of a copy of an official gazette published in 1933 and the land’s plan, which was older than thirty years. Likewise, official gazettes, a duly registered instrument, endorse the same pre-emptive presumption.[125] Essentially, registration is a certification that raises the presumption of its correctness as provided by section 79 of the Evidence Act.[126] Permissive presumption admits complete discretion to the Court to decide whether a party should be allowed such favour[127] unless witnesses are available, whereby again the Court may discretionarily elect not to embrace such presumption.[128]

- Cases of Criminal Jurisdiction

A presumption of fact alludes to the extensive discretion of the Court.[129] When a rule of law and prudence hits the highway of divergence, circumstantial evidence comes in handy. Rashed Kabir v State[130] addressed the contradicting views between the principles relating to an accomplice provided in Section 133 and Illustration (b) of Section 114. Therein, the Court insisted on corroboration of such insofar as it incriminated the accused. Generally, a confession recorded by a competent Magistrate possesses quasi-judicial characteristics and comes attached with the presumption of its genuineness, professed voluntarily without coercion.[131] However, in the case of an accomplice, it comes with the tendency to be tainted. Hence, materializing the necessity of corroboration. A presumption exists only on evidence produced as a record in a judicial proceeding. The significance of that statement can be seen in the case of Hossain alias Foran Miah v State.[132] Therein, the statement recorded and the medical reports marked as exhibits were not done according to law, which renders it unadmitted, whereby presumption ceased to exist. On the subject of cessation of presumption, suppressing material evidence or witness evolves adverse presumption, i.e., presumption turns its table towards the opposition.[133] Exempli gratia, the unexplained non-production of a witness,[134] exclusion of a material witness,[135] etcetera raises the adverse presumption against the prosecution. However, not every charge sheeted witness is material, and the non-production of any such witness does not lead to an adverse presumption against the prosecution.[136] Material witnesses are those who have experienced the event first-hand. Inferring from such, every eyewitness is a material witness. Non-examination of a few witnesses named in the charge sheet who are not eyewitnesses does neither fulfil the criteria of a material witness nor does the non-examination of such witness suffer at the expense of negative presumption.[137] Documents are material evidence, especially the ones certified or official records; such document walks hand in hand with the presumption of its authenticity.[138]

- Discretion: Civil Jurisdiction

In this section, discretionary power provided by various civil statutes, such as the Specific Relief Act of 1877 and the Code of Civil Procedure 1908, etcetera empowering various civil judges, is extensively discussed. Tayeeb (Md) v Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh[139] reconfirmed that the Superior Court's jurisdictions provided under the sacred sanctity of the Constitution must never be thwarted by rules. The suo moto rule exists as a mode of reassurance of law safeguarding the interest of the helpless.

- Discretionary Inherent Power

Commonwealth courts in Bangladesh have been exercising inherent jurisdictions long before the codification of the procedural laws. Inherent jurisdiction is complementary to the rest of the procedural laws[140] based on its characteristic vastness, residuum nature and not controlled by any other provision.[141] Such immensity of power is tempting. Isn't it? However, the language used in the provision often presents inherent power as unfettered,[142] which is figuratively true, but prudence speaks otherwise. MH Ali v J Abedin[143] provides that the inherent power is not an absolute discretion or a blank cheque for the Court to fill according to its whims. The denomination of inherent power is inherent within the essence of ex debito justitiae,[144] i.e., the absolute necessity for the ends of justice or to prevent abuse of power (MH Ali v J Abedin, 1985). To simplify, the Court's inherent power erases the boundaries. It empowers the Court to pass any order at its discretion to secure justice[145] and enhances confidence in the justice system. The intention behind conferring such jurisdiction is apparent in the impossibility of the legislature to even fathom contemplating all surroundings which may emerge in future litigations,[146] and time has been evidence of it. Undoubtedly inherent powers are vast, and within its vastness, it must display due cognizance to the express provisions of law[147] while aiming at the ends of justice,[148] applying its judicial mind and being satisfied on the facts and circumstances of each individual ease.[149] Alluding to the expression' ends of justice,' contextually, it literally means to disregard the established principles and norms of law to ensure justice.[150] On the other hand, the term ‘disregard’ is never synonymous with an arbitrary, fanciful, wrongful exercise of such discretionary jurisdiction.[151] In conclusion, the inherent discretionary jurisdiction is not unfettered. Such must be exercised having due regard to the express provisions of law and principles of equity,[152] as one who seeks equity must do equity and act promptly to secure ends of justice because justice neither knows nor entertains dirty hands or negligence.

- Amending Discretion

- Discretion to Amend Time

In Idris Shaikh v Jilamon Bewa,[153] the Court reserved the discretionary jurisdiction for extending time even in cases where the decree limits time for execution. Discretion relating to the enlargement of time contemplated under section 148 of the Civil Procedure Code, 1908, extends to proceedings in all suits, excluding the suits wherein time is statutorily demarcated.[154] The discretion and the scope of the relevant provision are minimal as it cannot materially affect the decree.[155]

- Discretion to Rectify

Vide the provisions of Section 152 of the Civil Procedure Code, 1908; the court is allowed to rectify its errors[156] of clerical or mathematical nature[157] surfacing from accidental slip or omission.[158] The said provision is the legislative acknowledgement of the court's inherent power.[159] However, amendments of substantial nature are discouraged.[160] Additionally, a judgement cannot be altered or affected with any addition after a judgement has been approved by attaching the presiding court's signature.[161] In Ismailullah v Sukumar Chandra Das,[162] the adjudged property was excluded from the category of the suit land, which according to the Apex Court, can be revised under section 152 while upholding the preliminary decree, and there exists no limitation of time relating to such amendment.

- Discretionary Transfer of Suits

‘Justice must not only be done, but it must also appear to be done’[163] is an established principle within the legal realm of Bangladesh. Keeping such in view, section 24 of the Civil Procedure Code, 1908 provides extensive discretion on the District Judge in matters relating to transfer and withdrawal of suits, appeals and other proceedings[164] available only to occasion ends of justice.[165] Further, it is inarguable that ends of justice can only be secured when discretion under the provision of section 24 is exercised judiciously, having applied judicial mind for the common convenience of both parties of the litigation.[166] For the sake of justice, the guidelines relating to transfer in Md. Jamal Hossain v Md Mazid[167] comes as an aid, viz.

- The litigant reasonably apprehends that justice shall be forsaken in the Court wherein the suit is pending:

Apprehension contemplated within the purview of this section must be justifiable, reasonable, and genuine, supported by specific concrete grounds.[168] In Kashem Khan (Md) v Md Shamsul Hoque Bhuiyan,[169] the submission of apprehension was that the defendant was seen to have entered the chamber of the Assistant Judge, which raised suspicion of receiving an unfair trial. Such grounds are invalid to invoke the provisions of transfer.

- Prevent multiplicity of proceedings or clashing decisions:

In Integrated Services Ltd v Khaleda Rahman,[170] the petitioners fraudulently secured an order of ad-interim injunction by suppressing the information of lis pendens of an earlier suit hence violating the clean hand requirement of equity. The Apex Court declared the order of injunction void and found the withdrawal of the first suit and its transfer for trial proper.

- The presiding judge is prejudiced towards one party and interested in the other:

In prudence, every presiding judge should maintain an impartial view while conducting the litigation and become funtus officio immediately after passing the decree.[171] However, in the event of an allegation of compromised impartiality, the onus lies on the applicant to show such prejudice to attain discretionary transfer of suit. Allegations of omission to record evidence in Sirajul Islam Shikder (Md) v Suruj Miah[172] were found immaterial and unreasonable. The allegation of bias must be real and cannot be based on mere assumptions, better understood vide the suit of Shahida Khatun v Abdul Malek Howlader and others,[173] therein the groundless allegation was that the party in opposition being a District Judge was presumed to be favoured.

- Common questions of law and fact arise between the parties in two or more suits, i.e., where a joinder of suits is possible.

- Balance of ease between both parties:

It is evident from the title itself that the transfer must be convenient for both concerned litigants,[174] e.g., the money suit of Shah Sekandar Molla v New Sagurnal Tea Co[175] was suo moto transferred for trial alongside another money suit for the ease of both parties.

- Wherein the cause of action is the same in two different suits instituted in two different courts:

Bijoy Kumar Basak v Narendra Nath Datta[176] held that suo moto transfer of a suit is administrative, discretionary, and exercised in the interest of justice. In the aforenamed suit, the two suits instituted in two different courts were transferred collectively for trial analogously; hence complications of proceedings could be avoided.

- Avert the suit from being delayed and cutting redundant expenses:

The Apex Court in Jamal Hossain (Md) v Md Mazid [177] found that the transfer of the suit inflicts immense trouble and heavy expenditure on both parties; hence rejected such prayer exercising discretion.

- Wherein the suit involves a significant question of law or a substantial Public Interest Litigation:

Justice should not only be done, but it should appear to have been done.[178] In Sree Satya Narayan Misra v Shamsuzzoha (1984),[179] the learned Additional District Judge was the trial court and also the presiding appellate Court in the same suit. Hence, the case was remanded to be heard for appeal by another judicial authority other than the alleged Additional District Judge.

- Deter the misapplication of the process of Court:

Zahir Sheikh v Md Yakub Ali (1991)[180] established that a Court is competent to try a suit relating to an immovable property beyond its territorial jurisdiction, provided a competent authority transfers such a suit. A suo moto order of transfer of suit must be notified to the other party and allowed the opportunity of being heard of its objections.[181] Every unobjected transfer of a suit is judicially presumed to have eliminated all grounds of apprehension.[182] Such does not amount to an abuse of the process of the Court.

- Discretionary Specific Reliefs & Exceptions

This study itself is solemn evidence that equity is the GPS[183] directing the pathway of discretion.[184] Principles of equity, like coming to the Court with a clean slate,[185] the conduct of the parties, circumstances of execution,[186] etcetera govern discretion. Equity also anticipates the plaintiff's willingness to perform the share of affairs.[187] The Specific Relief Act (1877) has explicitly defined every relief under the statute as discretionary. Given that discretion is endowed with characteristic broad jurisdiction, such vast powers cannot be constricted to a prescribed set of rules when it comes to granting a discretionary specific relief.[188] However, refusal of such relief is constrained to the provisions of Section 22 of the aforementioned statute.[189] Having mentioned that contracts are usually regarded as the foundation of all civil aspects, e.g., paperwork related to establishing a business facility is an implied contract between the government and the institution: the grounds being the facility furnishes the government with the imposed taxes, and in return, the business facility is permitted to sale its commodities, the sale of both movable and immovable property is a contract, marriage according to the Muslim traditions is a contract of civil union, etcetera. Therefore, civil reliefs revolve around the centerpiece of the contract in the form of specific performance, including assertive or preventive remedies like reinstating possession of forceful dispossession of immovable property, an injunction to maintain the status quo of immovable property, etcetera., respectively.[190] A contract appropriately executed have inviolability of its own[191] and by virtue raises the presumption of the crucial elements of a contract like genuineness,[192] thereby delivering the Court in a position to execute its discretionary power more independently than its ordinary jurisdictions.[193] From the trend above, it is well settled that the Courts are empowered to exercise broad scope of judicious,[194] non-arbitrary, reasonable, sound discretion, guided by judicial principles[195] in granting specific performance. On the other hand, refusal of such equitable relief is scrutinized at par with the entirety of the provisions of Section 22 of the Specific Relief Act.[196] However, in either of those cases, circumstantial evidence is a prominent source of adjudication.[197] The principles relating to non-granting of specific performance enunciated in Latifur Rahman v Golam Ahmed Shah[198] have been reaffirmed in numerous succeeding decisions like Shah Alam v Abdul Hashem Bepari (2002).[199] In those spirits, the constraining grounds provided in Section 22 of the Specific Relief Act, 1877 are enlisted hereinbelow:

- Instances wherein the plaintiff attains undue advantage over the defendant.

- Instances whereby the specific performance puts the defendant in a position of unforeseen/unwarranted burden, whereas its non-performance does not affect the plaintiff.

- Instances wherein the plaintiff is inflicted with irreparable loss due to the performance of substantial acts of the contract.

- Exception: Attainment of Undue Advantage

The discretionary decree of specific performance under the Specific Relief Act 1877 is a revolting one. Based on the fact that there exists no binding clause on the Court to grant such relief just because it is lawful, even in instances whereby the disputed contract is proved, but the prosecution comes to the Court not doing equity but expecting equity.[200] Such equitable relief may be rejected. In Jahangir Alam Sarkar v Motaleb,[201] the plaintiff orchestrated unclean hands by premediating to grab the suit property unlawfully. Along with the subsistence of a lawful contract, specific performance stands on the grounds of being denied provided the alleged contract was not duly executed,[202] non-payment of the due consideration,[203] good faith of the plaintiff is non-existent, a third party is disadvantaged,[204] the purpose of the contract was not upheld,[205] the unwillingness of performance of obligations within a justifiable period,[206] laches or delayed enforcement of the infringed rights,[207] etcetera, therefore, failing to attract judicial confidence and belief.[208] Every grant of specific performance must not otherwise fall within the mischief of allowing undue advantage to the plaintiff. In Jogesh Chandra Das v Farida Hasan,[209] the plaintiff allowed the defendant to remain in possession of the disputed property and did not attempt to gain possession. Such disengagement to obtain possession could not be reasonably accounted for by the plaintiff, also additionally, the defendant remaining in possession invested and brought about developments to the disputed property. Keeping all those factors in mind, the Court concluded that the plaintiff would be advantaged over the defendant if specific performance is decreed. Equitable standards, hereinabove, must always succeed the 'being reasonable' test, i.e., being proper, fair, unprejudiced, or moderate.[210] To consider a few examples, the consideration money must be reasonably adequate.[211] A third-party purchaser must never be deprived of rights of ownership; the proper course is to decree specific performance; hence the third party does not suffer loss.[212] Furthermore, the significance of the maxim vigilantibus iura scripta sunt, i.e., in this context, the necessity of establishing a written contract, cannot be accentuated enough.[213] Keeping in mind that the plea of specific performance of an oral contract encumbers the heavy onus of proof on the prosecuting party.[214] It obliges proof of the legitimacy of such oral contract by consistent evidence.[215] Addressing legitimacy in Chairman, RAJUK v Manzur Ahmed,[216] the very instrument of power of attorney failed to appeal to the judicial mind on the equitable grounds that the defendant had passed away at the initial stages of the suit. Legitimacy is a question of bonafide claims that fall within the purview of the law. To better understand the above, trespassing is a criminal offense, and trespassers cannot claim the title on an intruding property and is liable to be evicted.[217] Regarding a bonafide claim being an equitable relief, the plaintiff usually attains an undue advantage over the defendant when an agreement inclines towards the factor of time as its essence. The mere inclusion of a void clause after the passage of a particular period is not sufficient grounds for denying specific performance.[218]

- Exception: Unwarranted Burden

Inevitably equity acts in personam.[219] The relief of specific performance is a discretionary relief which, therefore, cannot be entertained as a rule based on the proof of the existence of the alleged contract. The Court, at its discretion, can elect to reject specific performance on the grounds of hardship.[220] The ground of hardship in prudence finds its cognoscibility in ab inconvenienti. It essentially denotes privation, adversity, or suffering,[221] which is to be considered against the circumstances existing at the time of the contract.[222]

Regarding privation, none should suffer at the expense of another, especially an innocent third party who, in good faith, purchases a property and is inflicted with hardship at the hands of the law.[223] Furthermore, when hardship befalls both parties, the Court applying the doctrines of equity looks to establish balance. For example, in Yousuf (Md) v Al-Haj MA Wahab,[224] the submission of the hardship of the defendant was rejected as the defendant would not become shelter-less and had alternative accommodation available in Dhaka and the contrary for the plaintiff. Sentimental values, such as homelessness, occupy prominent regions of the grounds of hardship.[225] Let's consider the case of Tahera Khatun v AKM Shafiul Islam and others,[226] whereby the plea of the hardship of the respondent having no other house in town and the appellant having no house in the country was compared parallel to each other. The Court recognized the significant hardship enveloping the appellant and decreed accordingly.

Furthermore, when hardship affects both sides, the safest guide and the safest approach is to examine the admitted facts and circumstances.[227] On another note, the plea of hardship resting on the argument of the sprouted price of a disputed property[228] or fluctuations of price[229] does not constitute a hardship. Plea of hardship does not always vitiate specific performance.[230] Along with such a plea, the additional grounds of equity, such as clean hands, etcetera., discussed above must be complied with.[231] Desperate times call for desperate measures, and one such despairing situation was the ground for rejecting the specific performance of a buy-sale contract in the case of Rash Behari Moshalkar v Hiran Bala Debi.[232] Therein the house of the defendant was listed for sale given the requirement of money for the treatment of one bedridden defendant and the educational expenses for the other defendant's son are satisfied. Such purposes were defeated. The plaintiff firstly falsely claimed payment of the consideration money in its totality hence not coming to the Court with clean hands; secondly, defeated the purpose of the agreement and thirdly, caused hardship on the defendant since the value of money depreciated over time. Moreover, a contract to establish a contract for the sale of land unreasonably burdens the selling party and is illegitimate and unenforceable in law.[233] Courts in Bangladesh discretionarily determine the legitimacy of the unwarranted burden on individual facts of each case. Such determination should not be arbitrary but the opposite, i.e., sound and reasonable, guided by judicial principles.[234]

- Discretion in Awarding Interest

Subject to the particular facts and circumstances of individual suits, the Courts are empowered to discretionarily award interest acting judiciously under the shade of judicial principles.[235] Nevertheless, discretion is never unfettered and is extinguishable by statutory provisions.[236] Generally, in civil suits, the award of interest is discretionary as provided by Section 34 of the Code of Civil Procedure 1908, which in the suit of Chalna Marine Products Ltd v Reliance Insurance Ltd and others [237] was suspended by the insertion of Section 47B of the Insurance Act, 1938. Such provision prescribed a five percent (5%) higher rate than the prevailing bank rate.

- Solatium

Courts in Bangladesh have adopted the view to discretionarily award solatium or compensation in cases involving hardships.[238] Whereby the award of solatium is an equitable relief against the non-grant of specific performance.[239] The compensatory award of solatium is the payment in addition to the consideration[240] and, like all discretionary processes, considers equitable aspects such as the award amount must be reasonable.[241] For example, Abdus Sobhan v Md Ahsanullah[242] held that solatium paid only considering the property's current market value defeats the principles of ab inconvenienti or the purpose of denying specific performance on the grounds of hardship as hardship can be nonfinancial. Furthermore, solatium is usually not denied because considerable time has elapsed from the execution of the contract to decree as price elevation due to elapsed time is a considered factor in calculating the solatium award.[243] However, the elevation of price is not a proper ground for hardship.[244] In Tobarak Ullah v Rani Gupta (1990),[245] the Apex Court increased the amount of solatium awarded by the High Court from Tk. 10,000 to Tk. 30,000 in total based on similar grounds as hereinabove.

- Discretion: Criminal Jurisdiction

The criminal statutes in Bangladesh embrace the doctrine of an 'act done in good faith.' Principally, the concept allows vast discretion and interpretation. Section 54 of the Penal Code, 1860 concerns due care and attention to every act claimed bonafide or done in good faith. The magnitude of care and attention is directly proportional to the degree of danger, i.e., the greater the peril, the greater the caution.[246] Moreover, the court's inherent power is no stranger to the criminal procedure, and the court(s) does not shy away from exercising discretion to secure the ends of justice. This section discusses a few instances whereby the court(s) discretionary resolves a matter.

- Discretion to Grant Bail

Conventionally, the term 'bail' denotes the temporary release of an arrestee. Such release demands assured attendance on a specific date, time, and at a particular place[247] and is a subject of judicial discretion guided by Constitutional and Statutory provisions.[248] Discretion related to bail is exercisable only for offenses prescribed 'non-bailable'[249] while having due judicial consideration of the circumstances of each individual case.[250] Captain (Rtd.) Nurul Huda v State[251] established that when exercising discretionary jurisdiction relating to bail for a non-bailable offense punishable with death or life imprisonment must not be proceeded on the presumption that it must be refused in all cases. Simply the heinousness of the offense is not sufficient for refusing bail without appreciating the materials on record.[252] Expanding on that thought, bail for offenses designated 'bailable' is granted as a matter of right,[253] and the Court has no discretionary power to refuse such statutory right.

Furthermore, granting bail as a matter of right for a non-bailable receives conflictive views. The High Court Division views it as a matter of concession.[254] However, such views can be overlooked vide the Apex Court decision of Begum Khaleda Zia v State.[255] Therein, procedural incompetence such as unfinished investigation,[256] inordinate delay in conducting the hearing of the case,[257] etcetera confers bail in a non-bailable offense as a matter of right. On revisiting the very definition of bail, along with the condition of secured attendance or non-abscission.[258] The granting of bail also demands non-interference with the investigation process, non-tampering of evidence, aversion from further committing any punishable offense,[259] elude recommissioning of the original offense,[260] etcetera. On similar standards, the High Court Division is endowed with broad discretionary jurisdiction to grant bail in cases relating to non-bailable offenses;[261] such broad discretion must, as a requirement, satisfy reason and logic while appreciating the evidence on record[262] and direction of law. Such judicious application of discretion is usually not impeded but for the interest of justice,[263] exempli gratia the enlarging of an accused on anticipatory bail for an indefinite time.[264] Within the circumference of comprehensive discretionary power exists sanctions for granting bail discretionarily for nonbailable offenses with prescribed short sentences.[265] Exercising such broad scope, the court(s) discretionarily grant bail in a non-bailable offense to establish a coherent equilibrium between characteristic traditional offenses and communal interest and divergent rights of individual freedom.[266] Assuming that varied faces of offense are on the rise, the Court(s) must adopt additional caution, judiciousness, and careful implementation of discretion with defined ground rules to prevent erroneous decisions or avoid the miscarriage of justice. Every miscarriage is pejorative to the mainstream interest of society.[267]

- Discretion in Awarding Sentence

In re awarding sentences, the penal provision in Bangladesh authorizes judges to apply discretion based on observations of the facts and circumstances of individual cases. To clarify, injuries inflicted by a sharp cutting weapon are usually grievous in nature; however, the severity of the offense is also to be measured by the inflicted body part, i.e., a sentence for a grievous hurt of the eye and that of the finger caused by the same weapon should not be the same.[268] Moreover, the penal laws extend the scope of discretion by providing multiple sentencing choices using the word ‘or.’ Considering the example of grievous hurt above, section 326 allows the presiding judge to award life imprisonment or imprisonment not exceeding ten years with fine.[269] The higher judicial body recognized the task of discretionarily awarding sentences as a ‘difficult assignment.’[270] In an effort to resolve the difficulty, Bushway & Forst proposed the notion of optimal sentence whereby the awarded sentence shall just be appropriate to accomplish its preferred outcome.[271] Such optimum sentence can be awarded by the balance of aggregate between the magnitude of the offense and the mitigating circumstances surrounding the offense[272] within the legislative proposition and expectation of the society at large, as justice must not only be done, but it must also appear to have been done.[273] Mitigating factors such as private defence, the plea of instigation, etc., are substantial compelling reasons which allow judges to travel the distance outside the sentencing guidelines.[274] While on the topic of sentencing guidelines, law academics in the United States professed the necessity of definitive sentencing based on its wide disparity. Hence came about the sentence reformation, which broadly focused on restricting judicial discretion.[275] Inconsistency of sentencing[276] is very consistent and compliant given the fact that the story behind every case is different, the offense is perpetrated differently, and the parties of the case are different humans.

- CONCLUSION

The doughnut theory perfectly demonstrates that discretion exists as a method of reassuring the general mass that equitable relief exists when the road of law appears to have come to an unprecedented end. The rule especially assures the socially considered helpless class of citizens that the hands of justice extend beyond view and that their interests are preserved. The above finds its roots in the combined principles of ex debito justitiae and ab inconvenenti. Therein, the Court's discretionary power is exercised to satisfy the ends of justice. Moreover, the truth of optima lex quae minimum relinquit arbitrio judicis and optimus judex qui minimum sibi must always be noticed as unsupervised discretionary jurisdiction is volatile and can be detrimental to law and order of any state. Phrases such as the Court thinks fit, the Court may suo moto, as the Court directs, as the Court deems proper, etcetera, empower the Court to apply discretion.

Furthermore, the vital aspect of any legal proceeding, i.e., evidence and witness, are admitted discretionarily by the Court. The Courts are permitted to presume any fact by exercising their discretion within the provisions provided by the Evidence Act. Every specific relief is an act of discretion, and the Court's discretion directs many procedural aspects of a trial. The above causes one to put on the thinking hat and analyse the predicament in the context of the statement by Anizman Philip, as truly discretion begins at the dawn of law and can inflict justice and injustice. Every occasion where injustice prevails due to discriminatory discretionary power must be considered a slap on the face of justice. The secondary type of discretionary power, i.e., supervised/ controlled/ monitored/ limited by rules and principles, whereby criticism of its correctness is allowed prevails within commonwealth Bangladesh. Such comforts the heart, knowing that the opportunity to inflict injustice is kerbed at least in black and white.

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author(s) take due cognizance of the blessings showered by Allah, the Eternally Gracious, the Everlasting Merciful. This research would not have arrived at its expected results without open access to late Advocate S.M Nazrul Islam Thandu’s law library, Ullapara. In due recognition of such, the author(s) salute the ethical professional accomplishments of the late learned Advocate and pray for his honour in the hereafter. This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

- CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Conflict of interest between the author(s) in all matters relating to this article is non-existent.

Bibliography

- Abani Mohan Sana vs. Assistant Custodian (SDO) Vested Property, 39 DLR (AD) 223 (1987).

- Abdul Aziz vs. Tafazzal Hossain, 50 DLR 487 (1998).

- Abdul Jabbar Sheikh vs. Md Rafiqul Islam, 16 BLC 639 (2011).

- Abdul Motaleb and others vs. Shahed Ali and others, 47 DLR (AD) 9 (1995).

- Abdul Munim vs. Mst. Hazera Zaman, 21 BLD 338 (2001).

- Abdur Rob Mollah vs. Shahbuddin Ahmed, 13 MLR (AD) 319 (2008).

- Abdus Sobhan (Md) vs. Md Ahsanullah, 21 BLC (AD) 268 (2016).

- Abdus Sobhan vs. Md Ahsanullah, 14 BLC 801 (2009).

- Abul Boshar (Md) vs. Minakhi Begum, 63 DLR 519 (2011).

- Abul Hossain vs. Amjad Hossain, 62 DLR (AD) 436 (2010).

- Abul Kaher Shahin vs. Emran Rashid, 25 BLC (AD) 115 (2020).

- ACC vs. Barrister Nazmul Huda, 60 DLR (AD) 57 (2008).

- Afroza Khatun vs. Momtaz Begum, 2 BLC (AD) 41 (1997).

- Agrani Bank vs. Orbit Enterprise Ltd, 61 DLR 710 (2009).

- Aja, N. C. (2022). Hart on Judicial Discretion: Sustaining Citizens’ Confidence in the Law. Humanities and Arts Academic Journal, 2(2), 10–16. https://www.cirdjournal.com/index.php/haaj/article/view/665

- Akbar Ali vs. State, 40 DLR 29 (1988).

- Akteruzzaman Zakir vs. Md Enamul Kabir Khokan, 73 DLR (AD) 376 (2021).

- Aljaber, M. J., & Al-Raqqad, A. M. (2021). The Discretionary Powers of the Civil Judge in Determining to Approve the Use of Personal Evidence as a Mean of Proof or Not. Journal of Legal, Ethical and Regulatory Issues, 24(3S), 1–13. https://www.abacademies.org/articles/the-discretionary-powers-of-the-civil-judge-in-determining-to-approve-the-use-of-personal-evidence-as-a-mean-of-proof-or-not-11846.html

- Amena Khatun vs. Chairman, Court of Settlement, 63 DLR (AD) 1 (2011).

- Amir Hossain Sowdagar vs. Harunur Rashid, 65 DLR (AD) 130 (2013).

- Anizman, Philip (ed.) (1975) A Catalogue of Discretionary Powers in the Revised Statutes of Canada, 1970. Ottawa: Law Reform Commission of Canada

- Aslam Khan vs. Haji Abdur Rahim, 12 MLR (AD) 149 (2007).

- Atiar Rahman & others vs. Mahatabuddin & others, 40 DLR 496 (1988).

- Azarova, E. (2019). Judicial discretion as an element of developing judicial law. Proceedings of the 1st International Scientific Practical Conference “the Individual and Society in the Modern Geopolitical Environment” (ISMGE 2019), 331. https://doi.org/10.2991/ismge-19.2019.13

- Azharul Islam vs. Md Idris Ali, 39 DLR 342 (1987).

- Babul vs. State, 42 DLR (AD) 186 (1990).

- Bachu Sheikh vs. State, 4 MLR 111 (1999).

- Bangladesh General Insurance Co Ltd vs. Chalna Marine Products Co Ltd, 51 DLR 357 (1999).

- Bangladesh Vs. Luxmi Bibi and others, 46 DLR (AD) 158 (1994).

- Bangladesh Water Development Board vs. GA Faiyaz Haider, 22 BLC (AD) 85 (2017).

- Bari SM. (2022). The legal aspect of rape: a review of the 2020 amendment of Nari O Shishu Ain (Act no VIII of 2000), Asian J. Soc. Sci. Leg. Stud., 4(2), 58-67, https://doi.org/10.34104/ajssls.022.058067

- Baude, W. (2020). Precedent and Discretion. 2019 the Supreme Court Review, 313-334 https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/journal_articles/10063/

- BD Shilpa Bank vs. Bangladesh Hotels, 38 DLR (AD) 70 (1986).

- Begum Khaleda Zia vs. State, 72 DLR (AD) 80 (2020).

- Bijoy Kumar Basak vs. Narendra Nath Datta, 43 DLR 68 (1991).

- Biplob Chandra Das vs. Biren Chandra Das, 52 DLR 586 (2000).

- Black, H. (2016). Black’s Law Dictionary(B. A. Garner, T. Jackson, & J. Newman, Eds.; Ninth, p. 534) [Review of Black’s Law Dictionary]. Thomson Reuters.

- Blaesser, B. W. (1994). The Abuse of Discretionary Power. Design Review, 42–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-2658-2_5

- BLAST and Others v Bangladesh & Others, 1 SCOB (AD) 1 (2015)

- Bodrul Ahsan vs. Janata Bank Ltd, 22 BLC 597 (2017).

- Bushway, S. D., & Forst, B. (2013). Studying Discretion in the Processes that Generate Criminal Justice Sanctions. Justice Quarterly, 30(2), 199–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2012.682604

- Bushway, S. D., Owens, E. G., & Piehl, A. M. (2012). Sentencing Guidelines and Judicial Discretion: Quasi-Experimental Evidence from Human Calculation Errors. Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, 9(2), 291–319. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-1461.2012.01254.x

- Captain (Rtd.) Nurul Huda vs. The State, 25 BCR (AD) 66 (2005).

- Catherine Masudvs. Md Kashed Miah, 70 DLR 349 (2018).

- Chairman, Bangladesh Agricultural Development Corporation (BADC) vs. Abedunnessa, 73 DLR (AD) 196 (2021).

- Chairman, Bangladesh Textile Mills Corp vs. Nasir Ahmed Chowdhury, 22 BLD (AD) 199 (2002).

- Chairman, RAJUK vs. Khan Mohammad Ameer, 26 BLC (AD) 219 (2021).

- Chairman, RAJUK vs. Manzur Ahmed @Manzoor Ahmed, 68 DLR (AD) 337 (2016).

- Chalna Marine Products Ltd vs. Reliance Insurance Ltd and others, 50 DLR ((AD) 100 (1998).

- Christie, G. (1986). An Essay on Discretion. Duke Law Journal, 35(5), 747–778. https://scholarship.law.duke.edu/dlj/vol35/iss5/1/

- CILEx Law School. (2018). Chapter 2: Equitable Remedies: Specific Performance. http://www.cilexlawschool.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/HQ05-Equity-and-Trusts-Sample-2018.pdf

- Correspondent, S. (2015, July 4). Masdar Hossain case verdict should be reviewed: Muhith. Bdnews24.com. https://bdnews24.com/bangladesh/masdar-hossain-case-verdict-should-be-reviewed-muhith

- Dayal Chandra Mondal vs. Assistant Custodian, ADC (Rev) Dhaka, 3 MLR 18 (1998).

- Desai, M.C (1996). Venkataramaiya’s Law Lexicon with Legal Maxims (2nd ed., Vol 1., p. 681). Law Publishers (India) Private Limited

- Dewan Abul Abbas vs. Muna Haque and others, 57 DLR 310 (2005).

- Dhanu Mia vs. State, 43 DLR (AD) 119 (1991).

- Divisional Estate Officer, Bangladesh Railway, Rail Bhaban, Dhaka vs. Jashimuddin, 24 BLC (AD) 36 (2019).

- DPEO vs. Joynal Abedin, 8 BCR 151 (1988).

- Durgarani Sarkar Vs. United Bank of India, 43 DLR 121 (1991).

- Dworkin, R. (1963). Judicial Discretion. The Journal of Philosophy, 60(21), 624. https://doi.org/10.2307/2023557

- Enamul Haque vs. Md. Ekramul Haque, 16 BLC 263 (2011).

- Ezaher Meah and others vs. Shaher Banu and others, 49 DLR (AD) 85 (1997).

- Feroja Khatoon Brajalal Nath, 43 DLR 160 (1991).

- Field, C. (1990). Law of Evidence (11th ed., Vol. 1, pp. 350–351). Law Publishers (India) Private Limited. (Original work published 1872)

- Field, C. (1990). Law of Evidence (11th ed., Vol. 5, pp. 4768–4769). Law Publishers (India) Private Limited. (Original work published 1872)

- Fletcher, G. (1984). Some Unwise Reflections about Discretion. Law & Contemp. Probs., 47(4), 269. https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship/1074/

- Gias Kamal Chowdhury and others vs. Dhaka University and others, 52 DLR 650 (2000).

- GM Bangladesh Railway vs. Mst. Sharifjan Bibi, 43 DLR (AD)112 (1991).

- Gouri Das vs. ABM Hasan Kabir, 55 DLR (AD) 52 (2003).

- Government of Bangladesh vs. Advocate Asaduzzaman Siddqui, 71 DLR (AD) 52 (2019).

- Government of Bangladesh vs. Amikun, 25 BLC (AD) 73 (2020).

- Goyal, R., Khan, I. M., Sharma, D., Kumar, R., & Nagar, U. S. (2022). Judicial Discretion. Uttarakhand Judicial & Legal Review, 2(1), 58. https://ujala.uk.gov.in/files/Ch8.pdf

- Grey, J. (1979). Discretion in Administrative Law. Osgoode Hall Law Journal, 17(1), 107–132. https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/ohlj/vol17/iss1/3/

- Griffith, G. (1994). Sentencing Guidelines and Judicial Discretion: A Review of the Current Debate (p. 8). NSW Parliamentary Library.

- Habibur Rahman alias Khorshed (Md) vs. Sree Brindaban Chandra Biswas, 26 BLC 725 (2021).

- Haji Md. Elias vs. Mrs. Suraya Rahman, 1 BCR 49 (1981).

- Hamida Begum Chowdhury vs. Ahamad Hossain Khan and ors, 50 DLR 276 (1998).

- Hari Rani Basak vs. Govt of Bangladesh, 13 BLC 1 (2008).

- Hasina Akhtar vs. Md Raihan & another, 66 DLR 298 (2014).

- Higgins, R. S., & Rubin, P. H. (1980). Judicial Discretion. The Journal of Legal Studies, 9(1), 129–138. http://www.jstor.org/stable/724041

- Hossain alias Foran Miah vs. State, 24 BCR (AD) 64 (2004).

- Idris Shaikh vs. Jilamon Bewa and others, 50 DLR (AD) 161 (1998).

- Integrated Services Ltd vs. Khaleda Rahman, 5 BLC (AD) 69 (2000).

- Ishaque Hosain Ch. vs. Shamsun Nessa Begum, 8 BCR 199 (1988).

- Ismailullah vs. Sukumar Chandra Das, 38 DLR (AD) 125 (1986).

- Jahangir Alam Sarkar vs. Dr. Motaleb, 11 MLR 273 (2006); 11 BLC 391 (2006).

- Jalaluddin Miah vs. Md Younus, 2 BCR 277 (1982).

- Jamal Hossain (Md) vs. Md Mazid, 12 BLC 452 (2007).

- Jogesh Chandra Das and others vs. Farida Hasan, 4 BCR (AD) 127 (1984).

- judicial discretion. (2020). LII / Legal Information Institute. https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/judicial_discretion#:~:text=Judicial%20discretion%20refers%20to%20a

- Kabir, L. (2019). Lectures on the Penal Code: With Leading Cases (A. Rakib, Ed.; 10th ed., pp. 47–49). Ain Prokashan.

- Kashem Khan (Md) vs. Md Shamsul Hoque Bhuiyan and others, 10 BLC 392 (2005).

- Kazi Fazlus Sobhan vs. Government of Bangladesh, 72 DLR (AD) 222 (2020).

- Kazi Rafiqul Islam vs. Md Anwar Hossain Advocate, 25 BLC (AD) 150 (2020).

- Kazuki, M. (2019). Politics and Independence of the Judiciary in Bangladesh. In IDE-JETRO (pp. 1–3). https://www.ide.go.jp/English/Publish/Reports/Rb/2018/2017240003.html

- Khairuzzaman (M) (Major Retd) vs. State, 4 MLR 75 (1999).

- Kilasonia, N. (2018). Judicial Control of Discretionary Power Used in Administrative Rule-making. Journal of Law, 1(1). https://jlaw.tsu.ge/index.php/JLaw/article/view/2574

- KN Enterprise vs. Eastern Bank Ltd, 63 DLR 370 (2011).

- Kotskulych, V. V. (2019). Specifics of Implementation of Judicial Consideration within Judicial Discretion. Jurisprudence Issues in the Development of Legal Literacy and Legal Awareness of Citizens, 100–116. https://doi.org/10.36059/978-966-397-151-3/100-116

- Kudrat Ali Mia vs. Aftabuddin Mia & others, 4 BCR (AD) 133 (1984).

- LaBattaglia, M. (2016). American Hospital Association v. Burwell: Correctly Choosing but Erroneously Applying Judicial Discretion in Mandamus Relief Concerning Agency Noncompliance. Maryland Law Review, 75(4), 1066. https://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/mlr/vol75/iss4/5/

- Latfur Rahman vs. Golam Ahmed Shah, 39 DLR (AD) 242 (1987).

- Latifur Rahman and others Vs. Golam Ahmed Shah & ors, 6 BCR (AD) 138 (1986).

- Li, L. (2014). Judicial Discretion within Adjudicative Committee Proceedings in China: A Bounded Rationality Analysis (p. 146). Springer. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-642-54041-7

- Liu, J., & Li, X. (2019). Legal Techniques for Rationalizing Biased Judicial Decisions: Evidence from Experiments with Real Judges. Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, 16(3), 1–41. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jels.12229

- Mascini, P. (2020). Discretion and the quest for controlled freedom (T. Evans & P. Hupe, Eds.). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-19566-3_9

- Mathura Mohan Pandit being dead his heir Sudhir Chandra Das vs. Hazera Khatun, 48 DLR 190 (1996).

- Jaker Ali vs. Abdur Rashid and others, 4 BCR (AD) 68 (1984).

- Jamal Hossain vs. MD Mazid, 11 MLR 409 (2006).

- Meyerson, D. (2015). Why Should Justice Be Seen to Be Done? Criminal Justice Ethics, 34(1),64–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/0731129x.2015.1019780

- MH Ali vs. J Abedin, 5 BCR (AD) 259 (1985).

- Mia Nuruddin (Apu) vs. State, 68 DLR (AD) 290 (2016).

- Monir, M. (1984). Principles and Digest of the Law of Evidence (Short Edition, p. 54; pp. 593-594). University Book Agency. (Original work published 1967)

- Monirul Islam vs. State, 22 BLC 414 (2017).

- Mosammat Kamrun Nessa vs. Abul Kashem, 2 MLR (AD) 220 (1997); 3 BLC (AD) 218 (1997).

- Mosammat Rohima Khatoon & anor Vs. Md. Abdur Rashid & the Govt of Bangladesh, 18 MLR 449 (2013).

- Moslimuddin Ahmed and others vs. Chandra Nath Ghosh and ors, 6 BLC (AD) 139 (2001).

- Moudad Ahmed vs. State, 71 DLR (AD) 25 (2019).

- Mozibur Rahman Moznu vs. Abdul Halim, 53 DLR (AD) 93 (2001).

- Mukherjee, T., & Singh, K. (1982). The Law Lexicon (3rd ed., Vol. 1, p. 530). Central Law Agency.

- Mullan, D., & Galligan, D. J. (1988). Discretionary Powers: A Study of Official Discretion. The University of Toronto Law Journal, 38(4), 420. https://doi.org/10.2307/82569

- Nasiruddin vs. Md Mozanunel Hossain, 63 DLR 303 (2011).

- Nayeb Ali (Md) vs. Md Abdus Salam Khan, 26 BLC (AD) 174 (2021).

- Nurul Islam and others vs. Jamila Khatun and others, 53 DLR (AD) 45 (2001).

- Pauline Kim. (2018, August 8). Lower Court Discretion. NYU Law Review. https://www.nyulawreview.org/issues/volume-82-number-2/lower-court-discretion/

- Pranay Kumar Malakar vs. Chowdhury Makhlisur Rahman, 26 BLC (AD) 40 (2021).

- Pratt, A. C. (1999). Dunking the Doughnut: Discretionary Power, Law and the Administration of the Canadian Immigration Act. Social & Legal Studies, 8(2), 199–226. https://doi.org/10.1177/096466399900800203

- Quazi Din Mohammad vs. Al-haj Arzan Ali and another, 47 DLR (AD) 48 (1995).

- Rakhal Chandra Dey vs. State, 7 BLC (AD) 84 (2002).

- Ram Chandra Das & ors, vs. Md. Khalilur Rahman and another, 4 BCR (AD) 364 (1984).

- Rash Behari Moshalkar vs. Hiran Bala Debi and another, 4 BCR (AD) 193 (1984).

- Rashed Kabir vs. State, 22 BLC (AD) 345 (2017).

- Reliable Jute Traders and another vs. Sonali Bank and others, 7 BLC 16 (2002).

- Reyes Molina, S. A. (2020). Judicial Discretion as a Result of Systemic Indeterminacy. Canadian Journal of Law & Jurisprudence, 33(2), 369–395. https://doi.org/10.1017/cjlj.2020.7

- Roberts, J. V. (2011). Sentencing Guidelines and Judicial Discretion: Evolution of the Duty of Courts to Comply in England and Wales. British Journal of Criminology, 51(6), 997–1013. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azr044

- Robi Axiata Ltd., Alias Axiata (Bangladesh) Ltd vs. First Labour Court, 21 BLC (AD) 218 (2016).

- Rupali Bank vs. Shawkat Ara Salauddin, 24 BCR (AD) 315 (2004).

- Sadrul Amin Budhu (Md) vs. Asaduzzaman and others, 4 BLC 340 (1999).

- Saimuddin vs. State, 43 DLR (AD) 151 (1991).

- Saipreethi, S., & Udayavani, V. (2018). A General Study on Inherent Powers of Courts Under Civil Procedure Code. International Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics, 120(5), 2529–2542. https://acadpubl.eu/hub/2018-120-5/3/213.pdf

- Sarafat Ali vs. Pranballav Sarkar, 18 BLD 157 (1998).

- Saroj Kumar Sarker vs. Monoj Kumar Sarker, 14 BLC 40 (2009).

- Schulz, W. F., & Davis, K. C. (1969). Review of Discretionary Justice, A Preliminary Inquiry. Administrative Law Review, 21(3), 411–419. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40708673?origin=JSTOR-pdf

- Shadharan Bima Corporation vs. First Court of Settlement, 13 MLR (AD) 241 (2008).

- Shah Alam (Md) vs. Abdul Hashan Bepari, 54 DLR 550 (2002).

- Shah Alam (Md.) vs. Abdul Hashem Bepari, 8 MLR 81 (2003).

- Shah Sekandar Molla vs. New Sagurnal Tea Co, 16 BLC (AD) 96 (2011).

- Shahida Khatun vs. Abdul Malek Howlader and others, 50 DLR (AD) 147 (1998).

- Shahidul Haque Bhuiyan (Md) vs. Chairman First Court of Settlement, 69 DLR (AD) 241 (2017).

- Shamsul Haque and others Vs. Sarafat Ali and others, 46 DLR 57 (1994).

- Shamsul Haque Dewan & others. vs. The state, 10 BCR (AD) 283 (1990).

- Sheikh Salimuddin vs. Ataur Rahman & others, 10 BCR 262 (1990).

- Siddiqur Rahman (Md) vs. Profulla Bala Devi, 50 DLR (AD) 213 (1998).

- Silver Estate Ltd. vs. Abdul Hakim Mia, 43 DLR 360 (1991).

- Sinai, Y., & Alberstein, M. (2015). Expanding Judicial Discretion: Between Legal and Conflict Considerations (pp. 221–277). Harvard Negotiation Law Review. https://www.hnlr.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/22/HNR202_crop-1.pdf

- Sirajul Islam Shikder (Md) vs. Suruj Miah, 12 BLC 299 (2007).

- Sklar, R. (2012). Executing Equity: The Broad Judicial Discretion to Stay the Execution of Death Sentences. Hofstra Law Review, 40(3). https://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlr/vol40/iss3/7

- Sree Satya Narayan Misra vs. Shamsuzzoha, 4 BCR (AD) 398 (1984).

- Standard Chartered Bank vs. Farook Paints and Varnish Manufacturing Company Ltd, 10 BLC 414 (2005).

- State represented by Deputy Commissioner vs. Md Palash, 20 BLC (AD) 348 (2015).

- State vs. Abdul Wahab Shah Chowdhury, 4 BLC (AD) 195 (1999).

- State vs. Arman, 67 DLR (AD) 181 (2015).

- State vs. Ful Mia, 5 BLC (AD) 41 (2000).

- State vs. Hazi Osman Gani, 16 BLC 504 (2011).