Typological characteristic of representation

##plugins.themes.bootstrap3.article.main##

Abstract

One of the forms of realization of the principle of private autonomy in civil law is fiduciary relations. In general, in contemporary law, the institution of representation is the basic cornerstone upon which many legal relationships are built. The importance of the institution increases one or two times in private law, when a person or an organization that, due to the various reasons in legal relations, is unable to represent its interests, starts to act and conduct legal actions through a representative. There are many reasons, however, the legislative is one, about which there are still some question marks, How comprehensive the Georgian legislation provides for the institution of representation, and what is the basic legislative framework, can be used to distinguish between forms of representation. For the development of the doctrine of private law, it is of great importance to bring to the fore the relevance and importance of the institution of representation. And for this, it is appropriate to conduct a study of the theoretical issues of the institute - the way from its historical beginnings to modern times. The typological characterization of the issue allows identifying problems on such important issues as the function of representation, its essence, its specific features, and signs, and how harmoniously the Georgian legislative framework is compatible with the standards established at the international level. And for this, it is appropriate to conduct a study of the theoretical issues of the institute - the way from its historical beginnings to modern times. The typological characterization of the issue allows identifying problems on such important issues as the function of representation, its essence, its specific features, and signs, and how harmoniously the Georgian legislative framework is compatible with the standards established at the international level. And for this, it is appropriate to conduct a study of the theoretical issues of the institute - the way from its historical beginnings to modern times. The typological characterization of the issue allows identifying problems on such important issues as the function of representation, its essence, its specific features, and signs, and how harmoniously the Georgian legislative framework is compatible with the standards established at the international level.

Keywords: Representation, Typology, Problem

Introduction

Representation is a legal institution regulated by the Civil Code of Georgia, the theoretical meaning of which acquires a characteristic legal nature during its practical implementation. The study will focus on several legal aspects of the typological characterization of representation. Representation is a legal institution regulated by the Civil Code of Georgia, the theoretical meaning of which acquires a characteristic legal nature during its practical implementation. The study will focus on several legal aspects of the typological characterization of representation.

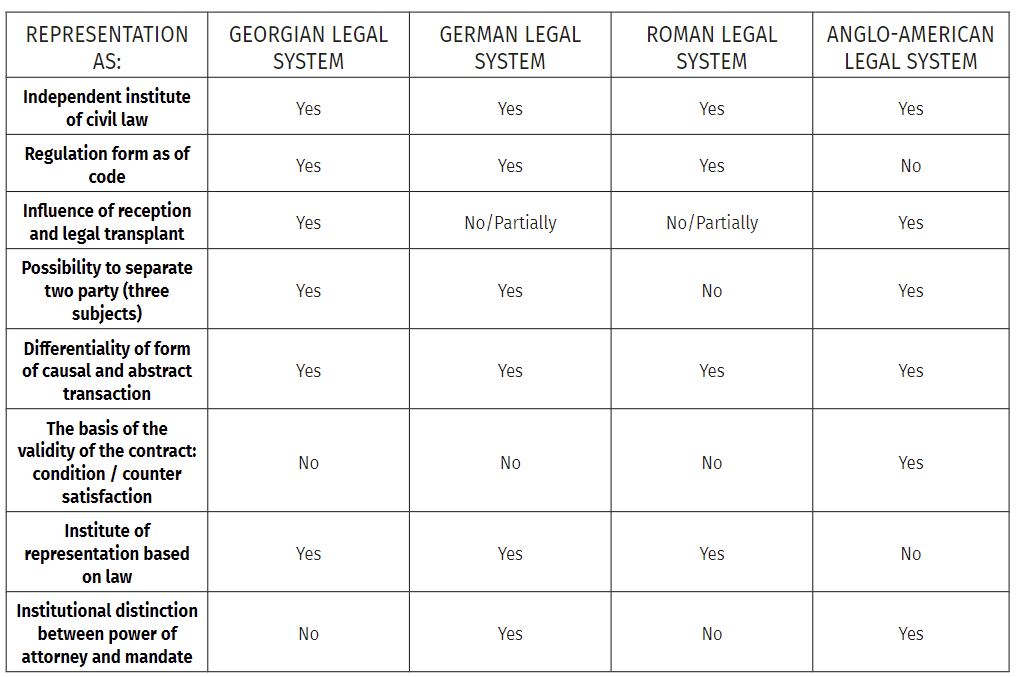

The issue of clarifying the characteristic features of the Georgian, German, Romanian and Anglo-American legal systems of representation is a criterion for evaluating the essence and functioning of this institution. This is what makes the system comparative context interesting, which, together with the challenges of Georgian private law, also includes the issue of regulation of the institution of representation by the code, which reveals the main concepts in the possibility of typological characterization of the issue.[1] Also, the typological characterization of representation implies the clarification of the meaning of the reception of law and legal transplant in private law. The purpose of the research is: to outline the essence and signs of representation; showing its origin as a Georgian institution of private law and its relation to legislative regulation in response to today's challenges; determining whether representation is permissible in all types of legal relationships under comparable legal systems. Normative, dogmatic, comparison, synthesis and analysis methods are used in the research.

1.Historical Aspects of Representation

Representation, as an institution of Georgian private law, existed in the form of customs and traditions even before the formation of the codified system.[2] In different social environments, representation acquired the form of both rights protection and tradition, which formed the moral, ethical and legal responsibility of the representative and represented person.[3] In Alexander Kazbegi's work “Khevisberi Gocha”, the episodic issue of Onise and Gugua is significant, where the control of the actions of the presented person was ensured by the phenomenon of moral justice.[4] Vazha Pshavela's poem “Bakhtrioni” in the form of Sanatha portrays the representation of issues of the deceased family members and men in a place where, as a rule, women are not allowed.[5] In the mediation process in Svaneti, representation was accepted in both criminal and civil cases.[6] The representation of the community and the representation of an individual are interesting. So, for example, the name of a mediator as a representative of justice and a neutral person can be found in the following form: judge, man of the law, makvshi, btche-mediator, khevisberi. A representative of an individual could be a family member or another person. In Adjara, “men to be called in advance” represented the opinion of the community. Representation in socio-political relations also had the function of guarantee.[7]

The regulation of the Civil Code of Georgia gave the institution of representation a characteristic (imported) form for the legal responsibility of natural or legal persons and private legal relations, including clarity of time and space.[8] Depending on the nature of legal relations in private law, the need is forming, that a person or an organization in the legal form of a legal entity, which, for some reasons, cannot directly exercise its interests, rights and duties, to be represented by a third person.[9]

This issue appears not only in private law, but also in public law relations.[10] Accordingly, the regulation of Articles 103-114 of Chapter 7 of the Second Book of the Civil Code of Georgia creates the legal basis for characterizing representation as an independent institution of Georgian private law. The named normative base also puts the issue of sectoral reflection and typological characterization in the private and public relations of the institution of representation on the agenda.[11]

Representation, as an institution of Georgian private law, is characterized by a heterogeneous manifestation of typological characterization for study disciplines in the same field. For example, for the method of solving a case in civil law, it is essentially a problem of manifestation of will,[12] more specifically: any problem arising at the time of making a transaction, which includes cases when it is possible to make a transaction, although the person who should become a direct party to the transaction does not participate in the conclusion of the transaction or this person makes an offer, but not an acceptance.[13] In the sciences studying the forms of alternative dispute resolution, representation is related to the ethical and procedural issues of the lawyer-representative's participation in mediation and notary mediation.[14] Also, the association agreement with the European Union represents an important stage in the Europeanization of Georgian private law, including the field of representation.[15]

Georgia is approaching European law step by step.[16] The process of development of Georgian private law, along with the general idea of law development, includes the development of separate legal institutions and legislative norms. Accordingly, the association agreement with the European Union, along with the convergence with the European legislation, carries the goal of developing Georgian private law. If Cicero thought that “all other laws ... were vague and ridiculous compared to the law of Rome”, in contrast to this concept, today, the development of different laws and separate legal institutions is an equal necessity today.

The adoption of the Civil Code of Georgia is the legal crown of Georgian statehood.[17] The regulation of representation as an institution of Georgian private law in the form of Articles 103-114 of the Civil Code, in turn, includes the possibility of its typological characterization.[18] It should be taken into account the fact that the legal acts of European countries, the European Union and the Council of Europe were studied while working on the draft of the Civil Code of Georgia, which shows the importance of the reception of the legal norm or the legal transplant as an example of the practical implementation of a separate institution.[19] It is natural that the institution of representation was formed on the basis of comparisons of Georgian peculiarities and legal norms and systems of different states.[20] If we compare from a historical point of view, for example, the ten-man commission (decemvirate)[21] of the Romans was responsible for the first plural law of Rome (the Law of the XII Table),[22] in which the creation of legal norms of representation as an institution of Roman law did not take place, the issue was regulated by other norms regulating Roman customary and social law, at the same time, it was related to the status of persons,[23] that is, their authority. Later, in the terminology of Roman law, the mandator was called[24] mandans, and the mandatary - procurator.[25] It is worth mentioning Savin's opinion that “the law grows with the people, is based on the people and disappears as soon as the people lose their individuality”.[26] Accordingly, the typological characterization of representation as an institution of Georgian private law is a definition with legal consequences of the current legislative regulation, which is based on a certain history in the sense of origin, concept or content. Representation as an institution of Georgian private law and its typological characterization is not only the subject and challenge of Georgian private law research, and within the framework of the obligation imposed by the association agreement with the European Union,[27] it is possible to develop a concept for a broad discussion of current issues.

2. Typological Characterization

2.1. Georgian Legal System

The typological characterization of representation as an institution of Georgian private law is a challenge of legislative reality and judicial practice in Georgian law. From a dogmatic point of view, the established sectoral classification,[28] in individual cases of practical reflection, is on the institutional border of private and public law, where the classification of legal families is of great importance from the point of view of discussion of the issue, and the typological characterization of sectoral forms of representation is the basis of its different perception for academic disciplines. It is interesting that the systematicity and institutionality of the institution of representation is conditioned by the historical formation of the institution and the current normative reality of the legislative regulation within the framework of the German, Roman and Anglo-American legal systems.

Moved by the spirit of the first constitution of the Democratic Republic of Georgia, the Georgian legal system (later - the legislature) after gaining independence, rejected the continuous operation of the constitutions, legislative acts and norms of the Soviet Socialist Republic, thus connecting the issue of state law and order and the development of law with the need to develop a form of reception and legal transplant.[29] According to the first sentence of the first part of Article 103 of the Civil Code of Georgia, the transaction can be concluded through a representative.[30] The named reservation gives natural and legal persons (hereinafter - representatives) the right to participate in private legal relations through a representative (capable person). According to the second sentence of the first part of the same article, the authority of the representative either derives from the law, or arises on the basis of a mandate (power of attorney).[31] In this form, the legislator determined the type of action based on the institution of representation: the code-based form of regulation and the consequential nature of voluntary reception.[32]

The current legislative version of the institution of representation, at the beginnings of the formation of Civil Code and afterwards, along with the similarity of this institution to the modern German legal system, it also forms separate features:

- a) regulation of legal representation in the regulatory chapter of transactions, as a necessity to refine the legislative technique;[33]

- b) the rule determined by the second part of Article 103 of the Civil Code of Georgia and the spirit of the legislator regarding the demarcation of the form of concluding a will, marriage, and at the same time other transactions that must be concluded directly;

- c) mandate (power of attorney) and authority, as the same basis for the origin of representative powers, as cases of common content and different terminological names.[34]

Similarity to the German legal model distinguishes the Georgian legal system from the Romanian and Anglo-American legal systems. It is possible to distinguish the following:

- a) The issue of regulation of representation as a private law institution by the Code. Also, the importance of voluntary reception and legal transplant in relation to the establishment of the institution of representation;

- b) issues of terminological naming and mutual separation of parties (subjects) of representation;

- c) issues of regulation of the rights and duties of subjects of representation as an institution;

- d) the question of the division of types and sectoral forms of the institution of representation.

One of the peculiarities of the Georgian model is the absence of a clear legal boundary between power of attorney and mandate. We can present the issue of terminological compliance with a problematic character, on the example of the legislation regulating notarial law. The title of Article 28 of Order No. 71 of the Minister of Justice of Georgia “On the procedure for performance of notarial acts” is: Performance of notarial acts on the basis of a power of attorney (authority, mandate agreement).[35] Let's look at the title and turn to the second sentence of the first part of Article 103 of the Civil Code of Georgia: the power of an agent may arise either by operation of law or out of a mandate (power of attorney). It is interesting why power of attorney includes the issue of authority and mandate agreement in the notary legislation, when in the Civil Code of Georgia, the legislator gives priority of reference to the mandate, and indicates the basis of the power of attorney in parentheses.[36] I wonder if this is a peculiarity or a legal flaw? The regulatory nature of Article 28 of Order No. 71 does not give specific importance to the issue of the power of attorney and mandate, and it distinguishes[37] the mentioned issue only by the peculiarity of drafting a public[38] and private[39] notarial deed. Unlike the named order, the Law of Georgia “On Notary” does not indicate the issue of mandate and power of attorney at all, but considers the latter within the framework of general or other notarial activity.[40]

It is necessary to assess what basic approaches have been established in judicial practice regarding the mentioned complex issue. According to the definition of the Supreme Court of Georgia, the granting of representative authority and the conclusion of an mandate agreement are two independent legal relations.[41] The court notes that the power of attorney, which confirms the representation, is very different from the contract of mandate, since, from a practical point of view, the latter regulates the relationship between the representative and the represented, while the power of attorney is aimed at ensuring the legal relationship between the represented and a third party.[42] i.e. the addressee of the power of attorney is a third party and serves to confirm the authority of the representative before him. The court draws a clear line between these two institutions and brings to the fore the main distinguishing features that establish the final legal framework for separating these two legal forms, in particular, according to the mentioned definition, the contract of mandate belongs to the type of contracts where the parties are: on the one hand, the mandator (the assignor), same as the creditor, and on the other hand, the mandatary, who performs the assigned action and appears in the role of the debtor. The subject of such a relationship can be the implementation of both legal and factual actions, for which a power of attorney can be issued or not issued at all. In this case, it is clear that the power of attorney can only be the basis for the existence of the relationship arising from the contract of mandate, but does not equate to this relationship itself. That is why, doctrinally, the grounds for terminating the contract of mandate (720-721 of the Civil Code) and the termination of authority (109 of the Civil Code) are regulated by different norms of the Code, which, as a rule, should avoid the existence of similar ambiguities and uncertainties in practice. We will touch on these and other issues more specifically in the third chapter of the work.

Representation in the Georgian legal system from the point of view of a separate part of the institution, echoes the broker, mediator, commissioner and other persons/institutions containing the actions of transferring the will, although despite the similarities, their legal nature and legal consequences are different. Legal representation may be called mandatory representation, and contractual representation - voluntary,[43] it is significant that the Anglo-American legal system does not dogmatically establish legal representation in the form recognized by continental law states. Division with mandatory and voluntary form as a division criterion derives from the nature of legislative regulation. For example, the division of notary mediation into mandatory and voluntary types in Georgian law is also determined by the form and nature of the regulatory norm. The legislator establishes the institution of representation in the Civil Code of Georgia with the following numbering and name:

- Article 103 – Concept;

- Article 104 – Agency and the effects of a transaction on an addressee;

- Article 105 – Limited legal capacity of an agent;

- Article 106 – Defect of the declaration of intent in agency;

- Article 107 – Power of agency;

- Article 108 – Obligation of notification upon changing the authority;

- Article 109 – Grounds for termination of power of agency;

- Article 110 – Obligation of agent upon extinguishment of authority;

- Article 111 – Entering into a transaction without a power of agency;

- Article 112 – Right to repudiate a contract;

- Article 113 – Agent’s obligation when there is a defect in the power of agency;

- Article 114 – Inadmissibility of entering into a transaction with oneself.

2.2. German Legal System

The German legal system with its history of formation and development, on the one hand, from the disintegrated state formation to the German Empire, from the Empire to the Weimar Republic, from the Weimar Republic to National Socialist Germany and after that, to the present day, and on the other, under the conditions of the state legal order of the Federal Republic of Germany, forms the centuries-old history of the institution of representation.[44] Title 5 of Division 3 of the First Book of the German Civil Code regulates the issue of representation and power of attorney.[45] We consider it permissible to indicate the numbering and name of the representation institution in the German Civil Code:[46]

- Section 164. Effect of declaration made by the agent;

- Section 165. Agent with limited capacity to contract;

- Section 166. Absence of intent; imputed knowledge;

- Section 167. Conferment of authority;

- Section 168. Expiry of authority;

- Section 169. Authority of authorized representative and the managing partner;

- Section 170. Period of effectiveness of the authority;

- Section 171. Period of effectiveness in the case of announcement;

- Section 172. Letter of authorization;

- Section 173. Period of effectiveness in the case of knowledge and negligent lack of knowledge;

- Section 174. Unilateral legal transaction by an authorized representative;

- Section 175. Return of the letter of authorization;

- Section 176. Declaration of invalidity of the letter of authorization;

- Section 177. Entry into contract by an unauthorized agent;

- Section 178. Right of revocation of the other party;

- Section 179. Liability of an unauthorized agent;

- Section 180. Unilateral legal transactions;

- Section 181. Contracting with oneself.

In terms of the volume of norms and the importance of the discussed issue, the German legal system indicates the institution of representation clearly, widely and inseparably to the substantive aspects of the issue.[47] This issue is characterized by a precise and complete legal regulation, which implies that representation in the German legal system should be allowed, first of all, in the legal relationship[48] in which the will of the representative is manifested on behalf of another person and within the scope of representative authority.[49]

Consider a practical example. In one of the German Federal Court cases, it was held that when consenting to enter into a contract using another person's eBay account, in connection with an online auction, it was acting on behalf of another person, to which the rules of representation would apply.[50]

In another case, a reservation was made that in each specific case, if the seller refrains from any contact with the buyer and entrusts the contractual negotiations to an intermediary until the last stage, the buyer can reasonably assume that the intermediary is using the seller's name and representative authority during the negotiation process.[51] Another case noted that, according to established practice, the application of the paragraph 164[52] and following ones of the German Civil Code is excluded in relation to pure real acts, such as the acquisition of direct ownership[53] (subject to certain exceptions[54]).

2.3. Roman Legal System

The revolutionary history of France and later, the power of the French Empire was not only distinguished from a political point of view,[55] the spirit of the development of the French Civil Code and its national and public dissemination as a unified model for the solution of social and legal relations is significant,[56] in order to establish a new order. There is a code that establishes the legal norms establishing and ensuring the institution of representation.[57]

According to the French Civil Code, the institution of representation is provided for in the form of code regulation, in the form of articles 1145-1161,[58] where the three subjects of the relationship, which is called the mandate relationship, are not institutionally separated from each other.[59] The two parties and the three entities are institutionally separated from each other in the German Civil Code. On the one hand, a specific internal relationship was established between the represented and the representative, which is built upon granting a power of attorney/authority to the representative by the represented, on the other hand, other features of the relationship between the represented and the third party are significant.

The assignment of authority is an abstract transaction, while the causal relationship exists in the form of a contract of assignment as a bilateral contract. The invalidity of the causal relationship does not affect the validity of the abstract transaction, which was reflected in the German Civil Code, and in the French Civil Code, the institution of representation was regulated within the scope of the contract of assignment, where the legislator distinguishes between the contract concluded on behalf of oneself and another. Signed on behalf of another person is a representation, signed on your own name is not. As a result, according to the French Civil Code, the power of attorney is included in the content of the mandate and is not separated from the latter. The reform implemented in 2016, which aims to change certain aspects of the content of Articles 1145-1161, has become an important challenge for French courts.

2.4. Anglo-American Legal System

The Anglo-American legal system develops the modification of the institution of representation from the foundations of the nature and history of the Anglo-American legal family. That is why the specificity of this system is determined by its different character from the continental legal system.[60] The influence of Roman law (as opposed to a separate legal mechanism) on English common law throughout its history of development was very minor and did not touch the foundations.[61]

In the typological characterization of the institution of representation from the point of view of system comparison, the Anglo-American legal system, together with the codified norms, also avoided relying on the institution on abstract concepts. Accordingly, he developed practical-legal precedents and theses of representation,[62] where representation, as an institution of private law, is a self-contained, self-regulating and customary law institution, which most shares the sharp character of different families of law. The systematicity of the English-American legal system is conditioned by the practical-legal understanding of representation. It is necessary to consider the structure of the liberal-constitutional state and the development of the economy and the legal provision of relations, including for practical purposes. In the context of system comparison, it is significant to what extent the institution of representation in the Anglo-American legal system has been influenced by the reception process and whether its results have been reflected in it. On the one hand, the process of voluntary reception, according to which the reception may be a conscious or unconscious aid step of various international organizations, can be evaluated positively. Crucial importance is attached to the bent paradigm, which can be positive or negative - it is considered bent by the country from which the law should be transferred.[63] As an example of forced implementation, we can consider the policy of an imperialist state in its own colony. Among them, the opening of the colony market for the products of the center, where the relationship between economic and legal paradigms is reflected. In the US, the general indignation against forced reception was manifested not only in legislative but also in political processes. American law was able to establish the institution of representation, partly in a spirit based on historical beginnings. The division of representation on behalf of others and on one's own behalf has not been established in this system. There is a principal or customer and an agent - a person who accepts the mandate to conclude a contract with a third party on his own behalf, although he is accountable to the principal, the legal relationship is called agency.

See Summary theoretical table.

Analysis of Decisions of the Supreme Court of Georgia

First, let's consider the existing judicial views on the institution of representation. The material and procedural nature of the institution of representation is shared in the practice of the Supreme Court of Georgia. From a material point of view, the court explains that “the institution of representation is based on the right of a specific person (or persons) to represent another person (or persons) in legal relations - the power of representation”.[64] The court points out how important it is to systematically analyze the procedural arrangement of the representative institution during the course of the case,[65] in order to outline each specific procedural perspective, to base it on the essentially correct definition-adjustment of the material basis.[66] In this sense, clarifying the procedural nature of the material basis should be aimed at the correct interpretation of its content.[67] From the procedural point of view, the Supreme Court notes in one of its decisions that in the case of court representation, if the party is unable to attend the sitting due to an honorable reason, this does not exempt his representative from also not attending the sitting, if he does not have an honorable reason for not appearing at the sitting.[68] In particular, “resolving this issue in a different way would make the existence of the institution of procedural representation meaningless”.[69] This issue is shared at the level of uniform practice. On the other hand, in another decision, the court uses the existence of the institution of representation as a means of excluding a specific issue for procedural purposes.[70] Accordingly, in practice, the opinion is recognized that the material basis of the institution and its practical manifestation should be in logical harmony with each other.[71]

The court connects the implementation of the institution of representation to a specific relationship, where the founding norm of this institution is supported by another norm useful for evaluating the existing relationship between the parties. In one of the decisions, the expression of the desire of the owner to sell the residential apartment through the representative was supported by the second sentence of the second part of Article 183 of the Civil Code,[72] however, in another case, the court indicates the importance of a specific legal relationship,[73] how important it is to study the nature of the relationship and the place of the institution of representation in this relationship.[74]

For the issue of representation of a legal entity, the court theoretically defines the legal aspects of the purpose of choosing to proceed through a representative and names the following: technical, psychological, humanitarian and structural aspects. After the content definition of the listed aspects, it is noted that “it is the institution of representation that serves to better protect the interests of the [legal] entity and achieve the above-mentioned goals”.[75] In another decision, the peculiarity of the assessment of the “problem of representation” in terms of the duty of loyalty[76] was noted, which derives from “the essence of representation, which obliges the representative to be guided by the interests of the represented person and not by personal interests.”[77] i.e. at the formal level, the material and procedural nature of the institution of representation is positively characterized in judicial practice, although the court develops different judgments regarding the content of representation.

Let's evaluate some content aspects of the institution of representation. Perceived is how important an already existing norm is for assessing the actual circumstances, even if this norm is flawed. The nature of the dispute is responsible for the multitude of problems of the content aspect.[78] The court explains in one of the cases that the plaintiff's claim, according to which the authority to receive the purchase money presented by the power of attorney is not confirmed by considering its content, is unfounded, because the consent to the transactional representation “can be given both orally and in writing”.[79] The issue of relationship between form and content is problematic and relevant. The question is what is more important, the content in the form, or the form nourished by the content. The court responds to this issue with the following reasoning: “The peculiarity of representation is expressed in the fact that the rights and duties of the transaction concluded by the representative within the scope of his authority arise only for the represented person. This is due to the fact that the representative acts on behalf of someone else and for someone else's interests. The transaction of the representative is the manifestation of the will, as a result of which the subjects of the relations that arise become represented and the third person.”[80]

Thus, when evaluating the practice of the Supreme Court of Georgia regarding the definition of the institution of representation, it is perceived that the typological characterization of the institution of representation is not relevant for the court, but rather the formal, casuistic and causal characterization is important,[81] which is based on the actual randomness of the assessment of the issue, and the legal reasoning, as a rule, is of a non-universal nature in relation to the main problem in theory. In relation to the main problem. Accordingly, the multitude of decisions, where the conceptual or substantive discussion of the issue of representation is given, does not lead to a common vision of the institution of representation.

As a counterbalance to the mentioned reasoning, let's consider some decisions from English judicial practice. The United Kingdom Supreme Court case Lloyd (Respondent) v Google LLC (Appellant) noted the particular importance of representation when a person or group of persons is unable to attend the trial.[82] In another case, Cramaso LLP (Appellant) v Ogilvie-Grant, Earl of Seafield and Others (Respondents), the difference in the legal effect of representation was explained in light of the existing dispute relationship. It can be said that the formal prerequisite for the admissibility of the institution of representation is met, although the substantive aspects differ according to the legal assessments of the trial court, regardless of whether there is anything in common between the content of the disputes.

Conclusion

The purpose of the study was to establish a typological characterization of representation; Determining the legal nature of representation as an institution of Georgian private law and its legal consequence. The study showed that the peculiarity of the legal regulation of the institution of representation, based on the question of quality and naturalness, is one of the motives for the development of effective methods of harmonizing[83] private legal relations and solving problems.

Finally, based on the research, the following conclusions were formed:

- During the review of the regulation on the specific features of the essence and meaning of representation, the legal framework, used to distinguish the forms of representation, was established.

- Along with the general contractual differences, the difference was expressed in the issue of the functioning of a separate form, when the social origin of the parties is formed into a relationship with legal consequences.

- In order to clarify the essence and purpose of the institution of representation, typological characterization is one of the important legal aspects, on the basis of which it is possible to determine the purpose of the institution and the form of its organization.

- For Georgian law, other legal systems are to some extent a means of characterizing the system-comparative context of the institution of representation, which produces legal results in judicial practice, taking into account the aspects of national legislation as well as harmonization with the EU legislation.

- The typological characterization of the institution of representation and the study of its legal character showed the necessity of developing sectoral forms and types in this direction.

Bibliography

Normative Materials:

- Civil Code of Georgia, 1997.

- Law of Georgia on Notaries, 2009.

- Minister of Justice of Georgia Order No. 71 “On Approval of Instructions for Notarial Act Performance Procedure”, 2010.

Scientific Literature:

- Amiranashvili, G. (2018). Compulsion to Form of Transaction as a Limitation of Freedom of Form. Tbilisi: “Meridiani”, p. 14. (In Georgian)

- Bichia, M. (2016). Legal Obligational Relations. Tbilisi: “Bona Causa”, p. 72. (In Georgian)

- Garishvili, M., Khoperia, M. (2010). Characteristics of Ancient Rome Law, Tbilisi, p. 215. (In Georgian)

- Erkvania, T., (2012). Protection of Third Persons’ Interests in Representation (According to the Civil Codes of Georgia and Germany). Justice and Law, №3 (34), pp. 38-39. (In Georgian)

- Zoidze, B. (2005). Reception of German Property Law in Georgia. Tbilisi: Training Center for Publishing, p. 184. (In Georgian)

- Zoidze, B., (2019). The Main Challenges of the Association on Agreement with the European Union for Georgian Private Law. Private Law Review, №2, pp. 12-13. (In Georgian)

- Tumanishvili, G. G. (2012). Introduction to Private Law of Georgia, Tbilisi: Ilia State University Press, p. 177. (In Georgian)

- Tumanishvili, G. G. (2012). Deals (Legal Nature and Normative Regulation), Tbilisi: Ilia State University Press, pp. 86, 90-91. (In Georgian)

- Kereselidze, D. (2009). General Concepts of Private Law. Tbilisi: Institute of European and Comparative Law Press, pp. 401-402. (In Georgian)

- I. (2014). The German Civil Code, Teaching Commentary, Chachanidze E., Darjania T., Totladze L. (eds.), 13th ed., Tbilisi: GIZ, § 164, 1. (In Georgian)

- Maisuradze, D., Darjania, T., Papuashvili, Sh. (2017). Case Book Civil Code General Part. Tbilisi: GIZ, pp. 83-84, 89. (In Georgian)

- Metreveli, V. (2013). Roman Law (Fundamentals), Tbilisi, pp. 9-10, 50. (In Georgian)

- Oppermann, Th., Classen C. D., Nettesheim M., (2021). Europarecht Ein Studienbuch, Tbilisi: GIZ, pp. 712-713. (In Georgian)

- Papidze, Kh., (2021). Legal Fundamentals of the Representation. Georgian-German Journal of Comparative Law, №7, pp. 16, 24-25. (In Georgian)

- Rusiashvili, G., (2021). Collusion and Abuse of Representative Authority. Georgian-German Journal of Comparative Law, №6, pp. 1-2. (In Georgian)

- Surguladze, N. (2002) Corpus Iuris Civilis. Tbilisi, p. 193. (In Georgian)

- Teteloshvili, B., (2022). The Lifetime Annuity Contract - Its Basics of Origin and the Rights and Obligations of the Parties (The Attitude of the Civil Code of Georgia to the Modern Trends in its Regulation). Tbilisi: “Georgika“, pp. 210-211. (In Georgian)

- Kardava, E. (2019). Association Agreement - a Special International Agreement with Specific Characteristics in the Book: Jorbenadze, S. (ed.), Sergo Jorbenadze 90, Tbilisi: Sulkhan-Saba Orbeliani University Press, p. 169. (In Georgian)

- Chiusi, T., (2019). Importance of Comparative Law for Georgia. Georgian-German Journal of Comparative Law, №2, pp. 2, 7. (In Georgian)

- Kandashvili, I. (2018). Judicial and Non-Judicial Forms of Alternative Dispute Resolution on the Example of Mediation in Georgia. Tbilisi: Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University Press, p. 223. (In Georgian)

- Kandashvili, I. (2020). Mediation (Effective Alternative Dispute Resolution), Tbilisi, pp. 188- 189. (In Georgian)

- Zweigert, K., Kitz, H. (2001). An Introduction to Comparative Law in the Private Law. 1st ed., Tbilisi: “GCI”, pp. 10, 200. (In Georgian)

- Zweigert, K., Kitz, H. (2001). An Introduction to Comparative Law in the Private Law. 2nd, Tbilisi: “GCI”, pp. 8-9. (In Georgian)

- Tskhadadze, K., (2012). The Need for the Institution of Representation in Administrative Law. “Journal of Law”, №1, p. 294. (In Georgian)

- Tskhadadze, K., (2016). Institute of Representation in Administrative Law. Tbilisi: Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University Press, pp. 21-22. (In Georgian)

- Chanturia, L., (2011). General Part of Civil Law. Tbilisi: “Law”, pp. 421-422, 424-425. (In Georgian)

- Jorbenadze, S. (2017). Commentary on Article 103 in the Book: Chanturia, L. (ed.), Commentary on the Civil Code of Georgia, Book I, Tbilisi, pp. 590- 591. (In Georgian)

- Brown, H., (2007). Napoleon Bonaparte, Political Prodigy, Journal of History Compass. Blackwell Publishing House, №5/4, pp. 1387-1388.

- Lobingier, C. S. (1918). Napoleon and his Code. Harvard Law Review, Vol. 32, №2, pp. 123-124.

- Fauvarque-Cosson, B., (2014). The French Contract Law Reform in a European Context. Elte Law Journal, №1, p. 67.

- Léon Julliot de La Morandière, (1948). The Reform of the French Civil Code. The University of Pennsylvania Law Review, Vol. 97, №1, pp. 1-2.

- Markesinis, B. S., Unberath, H., Johnston, A. (2006). The German Law of Contract, A Comparative Treatise, 2nd ed., Oxford/Portland, Oregon, pp. 65, 412-413.

- MüKo/Schubert, BGB, 7. Aufl., 2015, § 164, Rn. 1 (in German).

- Pieck, M., (1996). A Study of the Significant Aspects of German Contract Law. Journal of Annual Survey of International & Comparative Law, Vol. 3, Issue 1, pp. 115-116.

Court Decisions:

- Ruling of the Supreme Court of Georgia in the Case №as-124-116-2017, Dated 23 July 2020. (In Georgian)

- Ruling of the Supreme Court of Georgia in the Case №as-800-2020, Dated 12 November 2020. (In Georgian)

- Ruling of the Supreme Court of Georgia in the Case №as-1281-2018, Dated 27 March 2019. (In Georgian)

- Ruling of the Supreme Court of Georgia in the Case №as-1178-1098-2017, Dated 26 March 2019. (In Georgian)

- Ruling of the Supreme Court of Georgia in the Case №as-1555-2018, Dated 7 June 2019. (In Georgian)

- Ruling of the Supreme Court of Georgia in the Case №as-766-766-2018, Dated 10 June 2019. (In Georgian)

- Ruling of the Supreme Court of Georgia in the Case №as-917-909(k-16), Dated 19 July 2019. (In Georgian)

- Ruling of the Supreme Court of Georgia in the Case №as-847-847-2018, Dated 25 September 2018. (In Georgian)

- Ruling of the Supreme Court of Georgia in the Case №as-678-649-2016, Dated 16 December 2016. (In Georgian)

- Ruling of the Supreme Court of Georgia in the Case №as-235-222-2015, Dated 16 March 2015. (In Georgian)

- Ruling of the Supreme Court of Georgia in the Case №as-951-989-2011, Dated 10 November 2011. (In Georgian)

- Ruling of the Supreme Court of Georgia in the Case №as-836-1078-04, Dated 23 June 2005. (In Georgian)

- BGH 11.05.2011 - VIII ZR 289/09.

- BGH 19.12.2014 - V ZR 194/13.

- The Supreme Court of the United Kingdom, Cramaso LLP (Appellant) v Ogilvie-Grant, Earl of Seafield and Others (Respondents).

- The Supreme Court of the United Kingdom, Lloyd (Respondent) v Google LLC (Appellant).

Footnotes

[1] Chiusi, T., (2019). Importance of Comparative Law for Georgia. Georgian-German Journal of Comparative Law, №2, p. 7.

[2] Jorbenadze, S. (2017). Commentary on Article 103 in the Book: Chanturia, L. (ed.), Commentary on the Civil Code of Georgia, Book I, Tbilisi, p. 590.

[3] Zweigert, K., Kitz, H. (2001). An Introduction to Comparative Law in the Private Law. 1st ed., Tbilisi: “GCI”, p. 10.

[4] Aleksandre Kazbegi, “Khevisberi Gocha”.

[5] Vazha Pshavela, “Bakhtrioni”.

[6] Kandashvili, I. (2018). Judicial and Non-Judicial Forms of Alternative Dispute Resolution on the Example of Mediation in Georgia. Tbilisi: Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University Press, p. 223.

[7] During the period of Guria's speeches in 1905, the Georgian intelligentsia stood as a representative and guarantor of the rebels in order to intercede with the Russian Empire in order to deport them or take other repressive measures. See Lortkifanidze, M., et al. (2012). History of Georgia in Four Volumes (Georgia in the 19th - 20th Centuries), Tbilisi: “Palitra L”, pp. 114-115.

[8] Papidze, Kh., (2021). Legal Fundamentals of the Representation. Georgian-German Journal of Comparative Law, №7, pp. 16.

[9] Tskhadadze, K., (2012). The Need for the Institution of Representation in Administrative Law. “Journal of Law”, №1, p. 294.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Jorbenadze, S. (2017). Commentary on Article 103 in the Book: Chanturia, L. (ed.), Commentary on the Civil Code of Georgia, Book I, Tbilisi, pp. 590-591.

[12] Maisuradze, D., Darjania, T., Papuashvili, Sh. (2017). Case Book Civil Code General Part. Tbilisi: GIZ, pp. 83-84.

[13] Ibid, p. 89.

[14] Kandashvili, I. (2020). Mediation (Effective Alternative Dispute Resolution), Tbilisi, pp. 188-189.

[15] Oppermann, Th., Classen C. D., Nettesheim M., (2021). Europarecht Ein Studienbuch, Tbilisi: GIZ, pp. 712-713.

[16] Zoidze, B., (2019). The Main Challenges of the Association on Agreement with the European Union for Georgian Private Law. Private Law Review, №2, p. 12.

[17] Ibid, p. 13.

[18] Comp. Kereselidze, D. (2009). General Concepts of Private Law. Tbilisi: Institute of European and Comparative Law Press, pp. 401-403.

[19] Rusiashvili, G., (2021). Collusion and Abuse of Representative Authority. Georgian-German Journal of Comparative Law, №6, pp. 1-2.

[20] Zoidze, B. (2005). Reception of German Property Law in Georgia. Tbilisi: Training Center for Publishing, p. 184.

[21] Metreveli, V. (2013). Roman Law (Fundamentals), Tbilisi, pp. 9-10.

[22] Chiusi, T., (2019). Importance of Comparative Law for Georgia. Georgian-German Journal of Comparative Law, №2, p. 2.

[23] Metreveli, V. (2013). Roman Law (Fundamentals), Tbilisi, p. 50.

[24] Amiranashvili, G. (2018). Compulsion to Form of Transaction as a Limitation of Freedom of Form. Tbilisi: “Meridiani”, p. 14.

[25] Garishvili, M., Khoperia, M. (2010). Characteristics of Ancient Rome Law, Tbilisi, p. 215. (In Georgian) Also, Comp. Bichia, M. (2016). Legal Obligational Relations. Tbilisi: “Bona Causa”, p. 72.

[26] Surguladze, N. (2002) Corpus Iuris Civilis. Tbilisi, p. 193.

[27] See. Maisuradze, D., Sulkhanishvili, E., Vashakidze, G. (2018). EU Private Law - Decisions and Materials, Consumer Protection law, Labor Law, Corporate Law, Competition Law. Part One, Tbilisi: Society for International Cooperation of Germany, pp. 26-28.

[28] Tumanishvili, G. G. (2012). Introduction to Private Law of Georgia, Tbilisi: Ilia State University Press, p. 177.

[29] Zweigert, K., Kitz, H. (2001). An Introduction to Comparative Law in the Private Law. 2nd ed., Tbilisi: “GCI”, pp. 8-9.

[30] Tumanishvili, G. G. (2012). Transactions (Legal Nature and Normative Regulation), Tbilisi: Ilia State University Press, pp. 86, 90-91.

[31] Comp. Kereselidze, D. (2009). General Concepts of Private Law. Tbilisi: Institute of European and Comparative Law Press, pp. 401-402.

[32] Chanturia, L., (2011). General Part of Civil Law. Tbilisi: “Law”, pp. 424-425.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Papidze, Kh., (2021). Legal Fundamentals of the Representation. Georgian-German Journal of Comparative Law, №7, pp. 24-25.

[35] Comp. Teteloshvili, B., (2022). The Lifetime Annuity Contract - Its Basics of Origin and the Rights and Obligations of the Parties (The Attitude of the Civil Code of Georgia to the Modern Trends in its Regulation). Tbilisi: “Georgika”, pp. 210-211.

[36] Civil Code of Georgia, 1997, Article 103.

[37] Minister of Justice of Georgia Order №71 “On Approval of Instructions for Notarial Act Performance Procedure”, 2010, Article 28, Paragraph 1.

[38] Ibid, Paragraph 3.

[39] See. Leonidze, I., (2021). Civil Liability of the Notary Mediator in Notarial Law (Legal Regulations and Institutional Challenges). Journal of Georgian National University SEU International Student Scientific Conference Papers: “SEU & Science”, pp. 279-283.

[40] Law of Georgia “On Notary”, 2009, Article 38, Paragraph 1, Sub-Paragraph “a”, Paragraph 2.

[41] Ruling of the Supreme Court of Georgia in the Case №as-39-486-06, Dated 8 September 2006.

[42] Ibid.

[43] See. Erkvania, T., (2012). Protection of Third Persons’ Interests in Representation (According to the Civil Codes of Georgia and Germany). “Justice and Law”, №3 (34), pp. 38-39.

[44] Pieck, M., (1996). A Study of the Significant Aspects of German Contract Law. Journal of Annual Survey of International & Comparative Law, Vol. 3, Issue 1, pp. 115-116.

[45] Markesinis, B. S., Unberath, H., Johnston, A. (2006). The German Law of Contract, A Comparative Treatise, 2nd ed., Oxford/Portland, Oregon, pp. 65, 412-413.

[46] German Civil Code [BGB].

[47] Kropholler. I. (2014). The German Civil Code, Teaching Commentary, Chachanidze E., Darjania T., Totladze L. (eds.), 13rd ed., Tbilisi: GIZ, p. 90, § 164, 1.

[48] Chanturia, L., (2011). General Part of Civil Law. Tbilisi: “Law”, pp. 421-422.

[49] See: Papidze, Kh., (2021). Legal Fundamentals of the Representation. Georgian-German Journal of Comparative Law, №7, p. 16 (in Georgian); Tskhadadze, K., (2016). Institute of Representation in Administrative Law. Tbilisi: Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University Press, pp. 21-22.

[50] BGH 11.05.2011 - VIII ZR 289/09.

[51] BGH 19.12.2014 - V ZR 194/13.

[52] See. § 164.

[53] See. BGHZ 8, 132; 16, 263 and § 950 BGB.

[54] Except of § 854 II BGB.

[55] Brown, H., (2007). Napoleon Bonaparte, Political Prodigy, Journal of History Compass. Blackwell Publishing House, №5/4, pp. 1387-1388.

[56] Lobingier, C.S. (1918). Napoleon and his Code. Harvard Law Review, Vol. 32, №2, pp. 123-124.

[57] Léon Julliot de La Morandière, (1948). The Reform of the French Civil Code. The University of Pennsylvania Law Review, Vol. 97, №1, pp. 1-2.

[58] See: <https://www.trans-lex.org/601101/_/french-civil-code-2016/> [Last Seen 25 September 2022]; Also, Code Napoleon of the French Civil Code, William Benning Law Bookseller, 1827.

[59] See. Fauvarque-Cosson, B., (2014). The French Contract Law Reform in a European Context. Elte Law Journal, №1, p. 67.

[60] Zoidze, B. (2018). The Impact of Basic Rights on Private Autonomy: Expansion or Limitation of Private Autonomy (Review of the Practice of the Constitutional Court of Georgia) in: Private Autonomy as a Fundamental Principle of Civil Law, Zarandia, T., Kurzynsky-Singer, E., Tbilisi: Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University Press, pp. 93-95.

[61] Zweigert, K., Kitz, H. (2001). An Introduction to Comparative Law in the Private Law. 1st ed., Tbilisi: “GCI”, p. 200.

[62] Comp. MüKo/Schubert, BGB, 7. Aufl., 2015, § 164, Rn. 1.

[63] Comp. Kropholler. I. (2014). The German Civil Code, Teaching Commentary, Chachanidze E., Darjania T., Totladze L. (eds.), 13rd ed., Tbilisi: GIZ, § 164, 1.

[64] Ruling of the Supreme Court of Georgia in the Case №as-1281-2018, Dated 27 March 2019.

[65] Comp. Dzlierishvili, Z., Tsertsvadze, G., Robakidze, I., Svanadze, G., Tsertsvadze, L., Janashia, L., (2014). Contract Law. Tbilisi: “Meridiani”, p. 35.

[66] Ruling of the Supreme Court of Georgia in the Case №as-1178-1098-2017, Dated 26 March 2019.

[67] Tumanishvili, G. G. (2012). Deals (Legal Nature and Normative Regulation), Tbilisi: Ilia State University Press, pp. 90-91.

[68] See: Ruling of the Supreme Court of Georgia in the Case №as-678-649-2016, Dated 16 December 2016 (in Georgian); Ruling of the Supreme Court of Georgia in the Case №as- 847-847-2018, Dated 25 September 2018 (in Georgian); Ruling of the Supreme Court of Georgia in the Case №as-1555-2018, Dated 7 June 2019.

[69] Ruling of the Supreme Court of Georgia in the Case №as-800-2020, Dated 12 November 2020.

[70] Ruling of the Supreme Court of Georgia in the Case №as-235-222-2015, Dated 16 March 2015.

[71] See. Chanturia, L., Civil Law. General Part in the Collection: Zarandia, T. (ed.), Fundamentals of Georgian Civil Law in Georgian Judicial Practice. Tbilisi: Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University, Faculty of Law, pp. 6-7.

[72] Ruling of the Supreme Court of Georgia in the Case №as-836-1078-04, Dated 23 June 2005.

[73] Comp. Okreshidze, G., (2020). Sub-representation (Judicial Practice). Georgian-German Journal of Comparative Law, №10, p. 64.

[74] Ruling of the Supreme Court of Georgia in the Case №as-951-989-2011, Dated 10 November 2011.

[75] Ruling of the Supreme Court of Georgia in the Case №as-917-909(k-16), Dated 19 July 2019.

[76] Comp. Okreshidze, G., (2020). Direct Representation in the Transaction (Judicial Practice). Georgian-German Journal of Comparative Law, №10, p. 63.

[77] Ruling of the Supreme Court of Georgia in the Case №as-766-766-2018, Dated 10 June 2019.

[78] Comp. Ahlgren, C., (2021). Access to Publicly Funded Legal Aid in England & Wales and Sweden – a Comparative Study. Örebro: Örebro Universitet, p. 26.

[79] See. Ruling of the Supreme Court of Georgia in the Case №as-191-2021, Dated 29 April 2022.

[80] See. Ruling of the Supreme Court of Georgia in the Case №as-124-116-2017, Dated 23 July 2020 (in Georgian) in Ruling of the Supreme Court of Georgia in the Case №as-127-124- 2011, Dated 5 September 2012.

[81] See. Kavshbaia, N., (2020). Invalidity of the Transfer of Ownership of an Item on Behalf of a Self-Guaranteed Heir (Judicial Practice). Georgian-German Journal of Comparative Law, №7, p. 71. Ruling of the Supreme Court of Georgia in the Case №as-543-516-2013, Dated 8 July 2013.

[82] The Supreme Court of the United Kingdom, Lloyd (Respondent) v Google LLC (Appellant), p. 13.

[83] Comp. Kardava, E. (2019). Association Agreement - a Special International Agreement with Specific Characteristics in the Book: Jorbenadze, S. (ed.), Sergo Jorbenadze 90, Tbilisi: Sulkhan-Saba Orbeliani University Press, p. 169.